The Volksgemeinschaft

All too often the Nazi ideology is dismissed as ‘window dressing’, designed to cover up the intentions of political and military power. Nazi ideology included Hitler’s cult of personality; the effort to reshape Germany into a world power and racial theory that glorified the Aryan race and described Jews, among others, as parasites. Although the Nazi leaders had these elements in mind, they were not constantly working towards implementing them in reality. Other less negative and destructive aspects formed the basis for their ideology: strengthening community ties, gaining control over industrialisation and creating a national culture that would transcend class differences. Nazism claimed to be a revolutionary doctrine but it called for a return to a simpler way of life. The Nazis invoked traditional values and the pastoral lifestyle of the past. They wanted to turn Germany into a world power, in which the industrialised world would be secondary to the agrarian countryside.

Nazism claimed to be a revolutionary doctrine but it called for a return to a simpler way of life. The Nazis invoked traditional values and the pastoral lifestyle of the past. They wanted to turn Germany into a world power, in which the industrialised world would be secondary to the agrarian countryside.

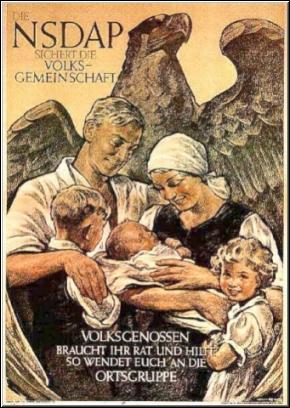

The key to National Socialism was the Volksgemeinschaft that was to replace the industrialised nation. It was a mass society in which equal participation from all individuals within the society replaced the earlier divisions on the basis of class. The National Socialist ideology longed for a total cultural transformation of German politics and society which would result in the community controlling every aspect of the individual’s life. The slogan "Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer" is based on this idea. The Nazi's wanted one people within a larger empire under Adolf Hitler's leadership. The goal of National Socialism was to penetrate the lives of individuals by creating a society in which everything and everyone was ‘coordinated’ by the guardian of the Volksgemeinschaft, the Nazi Party.

Women in the Volksgemeinschaft

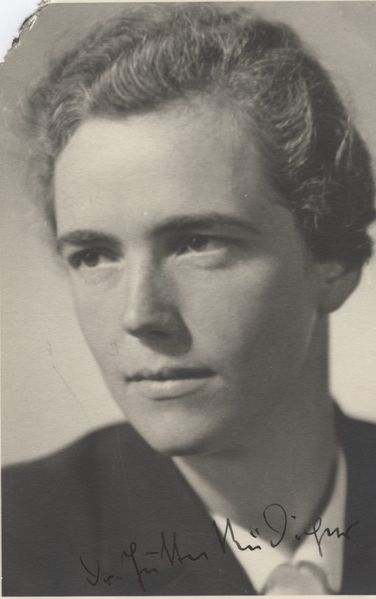

Women played a vital role as mothers and partners but also as a potential source of labour. The Nazi attitude towards women was reactionary. They were strongly opposed to the emancipation of women. They emphasised that men and women had different roles in society, based on biological differences. Women were not inferior but 'different' and should concentrate on their natural role as housewives and mothers. Politics was a man’s job so women were banned from the highest positions within the Nazi party, except within their own organisations such as the League of German Girls (Bund Deutscher Mädel). In a speech for a gathering of the National Socialist Women’s League on 8th September 1934, Hitler dismissed the emancipation of women as a Jewish intellectual invention. In the golden ages of German life, women had no need for emancipation. The world of the male was that of the state and the struggle and effort for the community. The woman’s world was smaller. Her world revolved around her husband, her family, her children and her home. The wider masculine world was built upon the foundations of the feminine world. His world could only survive if hers was stable. Therefore, Hitler thought it was wrong for women to invade the man's sphere. The two worlds should remain separate. This shows another contradiction in Nazi ideology since the Nazi society wanted to remove all inequalities and class differences (between Aryans). However, because of their views on men and women, a new division was created.

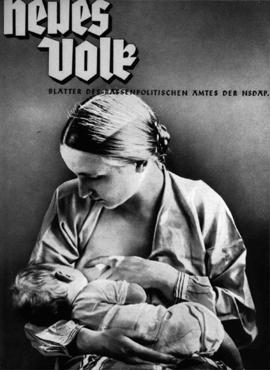

Motherhood was the most important role for women. As in almost all European countries, Germany was confronted with falling birth rates in the 1920s. The Nazi’s were worried that if the birth rate would continue to decrease, Germany would be unsuccessful in taking its place as a world power. There were several measures to stop the trend. A ban on abortion was more strongly enforced and there were monetary incentives to have children. The most original idea was the ‘marriage loan’. Marriage was encouraged by giving married couples the opportunity to lend money more easily and cheaply (without interest). Another measure was the improvement of facilities for pregnant women. The umbrella women’s organisation, the Deutsches Frauenwerk (DFW), organised ‘mother schools' where lessons were given about housekeeping and the skills of motherhood. The number of marriages rose: from 516,000 in 1932 to 740,200 in 1934, but the number of children did not increase proportionally. Many couples chose to have one or two children because they were worried that the extra costs of additional children would outweigh the financial benefits.

It is uncertain what impact the measures had on birth rates. The number of births only rose after 1933 but was still below the level of the period between 1922-1926. The increase was partially influenced by a rising faith in the future as a result of the improved economic situation. Also, more younger people married during the interbellum which meant that there were more married couples who could have children over a longer period of time. What can be ascertained is that couples that married after the Nazi seize of power had fewer children than couples during the 1920s. Nazi propaganda had very little direct effect on the birth rate but indirectly they were responsible for breaking the trend of falling birth rates by turning the economy around. This restored the Germans’ trust in the future and offered them a better quality of life.

The Nazi regime paid much attention to the physical and psychological health of babies. To guarantee the 'racial purity of the Aryans’, a law was declared in 1933 that prescribed forced sterilisation to men and women who were ‘inferior’ in the eyes of the Nazis, due to real or alleged hereditary illnesses. This law formed the basis of National Socialist racial hygiene, aimed at ‘regeneration of the race’ or in other words ‘the hygienic purification of the race'. In August 1935, marriages and sexual relations between Germans and Jews were officially banned. "The community has the right to prevent people from reproducing if one knows that their children will be physically, mentally and spiritually inferior," declared Dr. Steche.

This sterilisation practice expounds the traditional ideas of the role of women in Nazi Germany. The National Socialist Women’s League and the employees of women’s magazines encouraged women to accept the sterilisation policy and to report possible candidates. To this end, they had to go against the traditional views of motherhood and the role of women as mothers. It was made clear to readers that not so much the birthing of children but the regeneration of the state was the new goal. "A woman’s motherly sentiments could have dangerous consequences" because "just like every form of egotism, it conflicts with the interests of the race".

Still, the Nazi ideology was orientated towards the woman's role as a housewife and mother. The regime relied on two women’s organisations, the Deutsches Frauenwerk (DFW) and the National Socialist Women’s League (Nationalsozialistische Frauenschaft, NSF). The Deutsches Frauenwerk, founded in October 1933, dominated the other women’s organisations. In May 1934, it began the Reichsmütterdienst (RMD). This organisation offered a course (Mütterschulung) to convince mothers of their important duties in raising children. By March 1939, 1.7 million women had attended almost 100,000 lessons by the RMD. The DFW also successfully began a service for housewives that offered lessons in learning to cope with the scarcity of resources and food. The DFW mostly had members in the middle class and attracted few working class women. While the DFW was aimed at teaching practical matters to the masses, the NSF was a more elite organisation. Its task was to indoctrinate German women into National Socialism but its achievements were meagre. Both the NSF and the DFW united many women but this was a sleeping majority that contributed little to the realisation of Nazi ideals.

Definitielijst

- division

- Military unit, usually consisting of one upto four regiments and usually making up a corps. In theory a division consists of 10,000 to 20,000 men.

- Führer

- German word for leader. During his reign of power Adolf Hitler was Führer of Nazi Germany.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- interbellum

- “Latin: Between war”. Years between the Great War and World War 2.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- National Socialism

- A political ideology drawn up by Hitler based on the superiority of the German race, the leader principle and fierce nationalism that was fed by the hard Peace of Versailles. National socialism was anti-democratic and racist. The doctrine was elaborated in Mein Kampf and organised in the NSDAP. From 1933 to 1945 National socialism was the basis of totalitarian Germany.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Nazism

- Abbreviation of national socialism.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- Socialism

- Political ideology aiming at slight or no class differences. Means of production are owned by the state. Evolved as a response to capitalism. Karl Marx tried to substantiate socialism scientific.

Images

Jutta Rüdiger, head of the League of German Girls (Bund Deutscher Mädel). Source: Wikipedia.

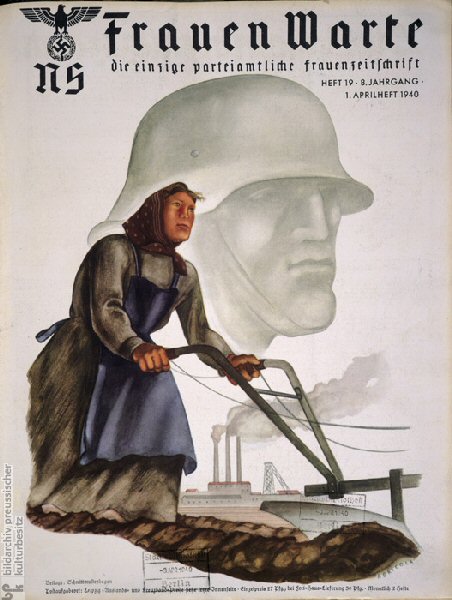

Jutta Rüdiger, head of the League of German Girls (Bund Deutscher Mädel). Source: Wikipedia. Frauenwarte, the magazine of the Nationalsozialistischen Frauenschaft. Source: German Historical Institute.

Frauenwarte, the magazine of the Nationalsozialistischen Frauenschaft. Source: German Historical Institute.The position of women in the German economy

The economic situation was dire when Hitler came to power. Germany was on the brink of bankruptcy. The decrease in income contributed to the radicalisation of the electorate after 1929 and the rise of the National Socialist movement. The Nazi leaders did not have a magic formula to solve the economic problems. In the early years, the attention went towards economic recovery. Once he had consolidated his power, Hitler chose to concentrate the economy on potential war, which implied greater interference by the government. Increased rearmament went hand in hand with greater autarky. The Four Year Plan, which began in 1936, was intended to make the German industry self-sufficient, particularly in oil, steel and rubber.

The most important goal was improving employment opportunities. The unemployment crisis was a key point in the Nazi attacks on the Weimar government. Between 1929 and 1933, the number of Germans working full-time fell from 20 million to 11.4 million. Interestingly enough, German women held a larger proportion of jobs than in other industrial countries. This, while they were officially registered as unemployed. The most important reason for this was the poor German economy. To battle against the recession, business leaders put women to work because they were cheaper. Initially the Nazi’s pushed women out of the economy.

Thanks to special projects, such as the construction of roads, bridges and houses and the promotion of the automobile and motor industry (for example, Volkswagen), unemployment fell slowly from 1933 onwards. The economic recovery is explained time and time again as a result of rearmament but that only became economically significant around 1934-1935 when the recovery had already begun. Why did it take so long for rearmament to pick up speed? Hitler saw the creation of employment opportunities and public investment as an important part of the social and material rebuilding of the country. Roads were the symbol of the new Nazi period. The first armament programmes were camouflaged to avoid conflict with the powers of the Treaty of Versailles. It was also unclear how military investments could be made without causing inflation. Finally, the military became a supporter of gradual rearmament because they did not want the economy to be overwhelmed after the heavy crisis. This made it difficult to quickly and effectively transform the economy into a war economy.

From 1936 onwards, the economy was being prepared for war. The production of luxury items was made secondary to military production. Indirect rearmament between 1936 and 1939 was more important than the direct production of military equipment because this way, the economy could slowly be transformed into a war economy and the number of educated labourers was expanded. The growing economic activity brought many women into heavy industry and the weapons sector. Between 1938 and 1941, the number of women in the chemical industry rose by 67% and by 59% in the metal industry. Nevertheless, the economy was not ready when war was declared in September 1939. The larger projects (such as oil production and the railways) were far from finished. The plans for the armament of the air force and the navy were not yet realised. Many of the problems that Germany faced during the war were as a result of the war's premature beginning.

In 1936, it became clear that Germany had too few workers. There was a shortage of workers outside of the traditional labour market. This meant that women had to be put to work and a switch in National Socialist labour politics was necessary. Until 1936, excluding women was an effective way to manipulate employment statistics. The Nazi’s created work for men by removing women from these positions. This was closely linked to the National Socialist belief in the biological function of women as mothers and housewives and was promoted by awarding loans with low interest to young married couples, on the condition that the wife would give up her job.

Due to the shortage of workers, the Nazi attitude changed but the measures for increasing female employment did not always have the desired effect. However, there was an increase in the proportion of women in the machine, mining and steel industries but at the same time the number women in the service industry increased by 166,000. The percentage of women in agriculture rose insufficiently which increased the burden of other workers. Many DAF reports stated that women in agricultural areas were overworked and were under great stress which sharply contrasted published propaganda. This contradiction also applied to the only pre-war measure regarding women’s labour that was put in place, women’s compulsory work service. In 1935 girls aged 16 and over were obliged to complete one year of compulsory labour as a housekeeper or in agriculture. On 1st January 1939 the measure was extended to all women under the age of 25. These measures were controversial. Hermann Göring stated that women should remain at home and should not work but he thought that, under the circumstances, the measures were justified.

It was often said that Germany did not sufficiently succeed in extracting the full benefit from female labour reserves in comparison to the UK and the USA. If Germany had succeeded in this, the country could have achieved much higher production numbers. Nazi ideology and the fear of demanding too much from the German public stood in the way. This theory was based on the fact that the absolute number of women labourers barely rose during the war, but it has since been refuted by several authors (Herbert, Stephenson and Overy). Germany already had a high rate of female labour at the end of the 1930s and during the war there was a reorganisation of female labourers into military sectors. The first point is of particular importance. The employment of women increased from 1935/6 as a result of the regime's labour policy. The increase was noticeable: From 13% to 19% in the iron, steel and machine industries, from 12% to 29% in electrical engineering and from 18% to 25% in the precision and optical instruments sector. In 1939, the number of employed women stood at 14.8 million or 37.4% In the UK it was ‘only’ 26.4%. During the war the number of women in German industry rose to 51%, however the number of British women in industry rose to just 37.9% This did not fit into the traditional view of the Nazis as fervent opposers of female employment. They indeed thought that it was not ideal that women (certainly married women) were working outside of the home, however they put their ideology aside due to labour shortages and for the ultimate goal of winning the war.

| Proportion of women in employment | |||||

| Germany | United Kingdom | United States | |||

| May 1939 | 37,3% | June 1939 | 26,4% | - | - |

| May 1940 | 41,4% | June 1940 | 29,8% | 1940 | 25,8% |

| May 1941 | 42,6% | June 1941 | 33,2% | 1941 | 26,6% |

| May 1942 | 46,0% | June 1942 | 36,1% | 1942 | 28,8% |

| May 1943 | 48,8% | June 1943 | 37,7% | 1943 | 34,2% |

| May 1944 | 51,0% | June 1944 | 37,9% | 1944 | 35,7% |

As explained before, there was a significant reorganisation of women labourers during the Second World War to benefit war production. The reorganisation had two parts. The first was a reorganisation within industry, an abandonment of goods for consumption and a turn towards war related sectors. The table below demonstrates this:

| The division of female labour in German industry (x 1000) | |||||

| May 1939 | May 1940 | May 1941 | May 1942 | May 1943 | |

| Capital goods | |||||

| - Chemicals | 184,5 | 197,4 | 204,7 | 215,8 | 255,9 |

| - Iron and steel | 14,7 | 18,4 | 29,6 | 36,3 | 64,9 |

| - Construction | 216,0 | 291,3 | 363,5 | 442,0 | 603,0 |

| - Electricals | 173,5 | 185,4 | 208,1 | 226,3 | 264,7 |

| - Precision and optical instruments | 32,2 | 37,2 | 47,6 | 55,6 | 67,2 |

| - Metal | 139,1 | 171,3 | 172,0 | 192,2 | 259,5 |

| Total | 760,2 | 901,3 | 1025,7 | 1168,4 | 1515,4 |

| Consumer goods | |||||

| - Printing | 97,2 | 88,8 | 92,6 | 73,9 | 60,1 |

| - Paper | 89,5 | 84,3 | 79,2 | 71,9 | 73,1 |

| - Leather | 103,6 | 78,7 | 85,0 | 81,8 | 95,6 |

| - Textile | 710,1 | 595,4 | 581,3 | 520,9 | 546,3 |

| - Clothing | 254,7 | 226,5 | 225,3 | 212,8 | 228,9 |

| - Ceramics | 45,3 | 41,4 | 39,5 | 37,1 | 42,8 |

| - Food | 324,6 | 273,5 | 260,9 | 236,8 | 238,0 |

| Total | 1625,3 | 1388,7 | 1364,0 | 1235,4 | 1284,5 |

The second part of the reorganisation was less noticeable yet still of importance. A large number of women worked in agriculture. Female employment rose by 230,000 between 1933 and 1939, while male employment fell by 640,000. During the war, women made up 54.5% of the German agricultural employment in 1939, 61.6% in May 1942 and 65.5% in 1944. Due to the conscription of agricultural workers for military service (in June 1941, more than one million men), more and more women were obliged to manage the farms, sometimes with assistance from foreign workers or prisoners of war. These women filled an important task since the agriculture sector was essential during the war. Furthermore, the extra help needed in busy periods (such as during harvests) was mostly provided by women. In the summer of 1942, one million Germans were recruited as temporary or permanent agricultural workers. This included 948,000 women. Many of this part-time work did not appear in statistics because only full-time labour was recorded. The same phenomenon occurred in other sectors. In June 1941, 600,000 men were recruited from the retail sector, and women were obliged to keep the cogs turning. Women took over jobs from men as post deliverers, bus drivers and railway workers. For women in office work, this meant a move to other work, more related to the war effort.

Due to the prevalence of women on the job market in pre-war Germany, it was difficult to achieve a further increase of employed females. However, one should not conclude that Germany failed to mobilise German women. The problem of such conclusions is that the work done by agricultural women, housekeepers, retail workers and so forth were not appreciated as being real work. Through the increasing number of men who were conscripted to the army, women had the ‘opportunity’ to carry out new tasks and take on greater responsibilities while at the same time maintaining a family. Women received a lower wage and worked longer days than men. The effect was that in 1939, there were already clear indications of failing standards of health among working women: exhaustion, increasing absences and hostility towards the wage gap. A doctor wrote in his report for the local mayor on the health of working women that the amount of depression and nervous conditions was increasing and recommended slowing down production. Such considerations prevented a larger recruitment of women for the labour market, more so than ideological views.

Definitielijst

- Four Year Plan

- A German economic plan focussing at all sectors of the economy whereby established production goals had to be achieved in four years time.

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- inflation

- An economic process of sustained increase in general price levels and devaluation of money.(loss of purchasing power)

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

Images

Passersby read Göring’s 9 policies to increase employment. Women were removed from the economy at first. Source: USHMM.

Passersby read Göring’s 9 policies to increase employment. Women were removed from the economy at first. Source: USHMM. Building motorways was one of the large projects that the Nazi’s set in motion to solve unemployment. In the photo, Hitler ceremonially takes the first shovel. Source: Hitler Historical Museum.

Building motorways was one of the large projects that the Nazi’s set in motion to solve unemployment. In the photo, Hitler ceremonially takes the first shovel. Source: Hitler Historical Museum. After 1936 women are brought back into the economy due to labour shortages. Here we see a group of young women on their way to work on the fields. Source: USHMM.

After 1936 women are brought back into the economy due to labour shortages. Here we see a group of young women on their way to work on the fields. Source: USHMM.Conclusion

What we can see from the split between the Nazi ideas on the position of women on the one hand and the realisation of this in practice on the other, is that there was no unity in the Nazi system. The ideology stated that a woman’s place was in the kitchen. Her role was to look after her husband and children. Intensive propaganda emphasised that nature had predetermined the woman’s role as a mother and housewife. Women had to produce children for their people and the nation. In agreement with the ideology, the Nazis removed women from the workplace up until 1936, to make way for men. A lack of sufficient labour forced the Nazis to change their policy. From 1936 onwards, measures were taken to increase female employment. This went against their ideology but at that time other rules were applicable, those of a wartime economy. German women were put to work so the quotas for military production could be reached. Moral and ideological considerations did not play a role in the question of labour. The Nazis wanted to see as many people as possible working, male or female. After they had won the war, they would have returned to their ideals. The war was of course never won and so, along with the Nazis, this new society faded away.

Definitielijst

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- Moral

- The will of the troops/civilians to keep fighting.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

Information

- Article by:

- Gerd Van der Auwera

- Translated by:

- Rachael Darwin

- Published on:

- 19-06-2013

- Last edit on:

- 15-06-2020

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Sources

- DURHAM, M, Women and fascism, Londen, 1998.

- HERBERT, U., Geschichte der Ausländerbeschäftigung in Deutschland 1880 bis 1980, Berlijn, 1986.

- HERBERT, U., Hitler's foreign workers, Cambridge, 1997.

- NOAKES, J. & PRIDHAM, G., Nazism 1919-1945: a history in documents and eyewitness accounts., New York, 1990.

- OVERY, R.J., War and economy in the Third Reich, Oxford, 1994.

- SAX, B. & KUNTZ, D., Inside Hitler's Germany, Lexington, 1992.

- STEPHENSON, J., Women in Nazi Society, Londen, 1975.

- WINKLER, D., Frauenarbeit im Dritten Reich, Hamburg, 1977.

- VAN DER AUWERA, G. De nazi-ideologie en de verplichte tewerkstelling van Belgische vrouwen in de Tweede Wereldoorlog: een confrontatie. Licentiaatsverhandeling, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 2001.