How the story of Horsa 166 and the 13 Platoon travels through time

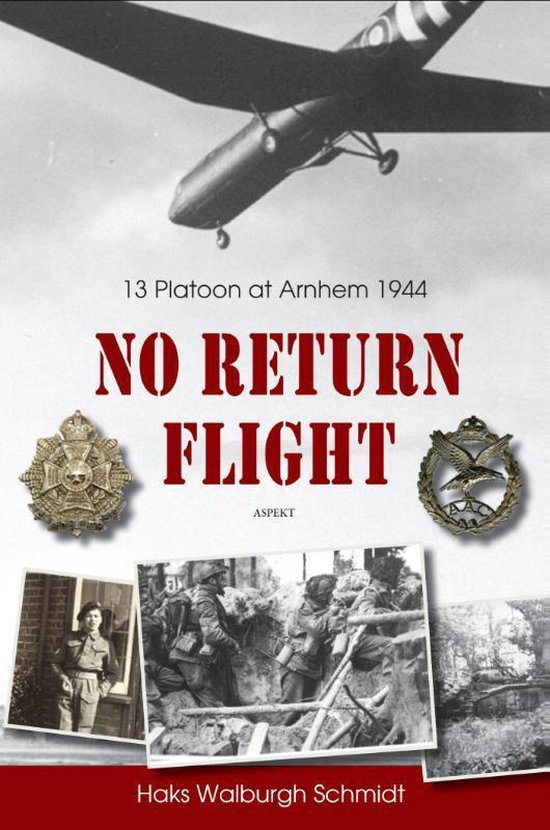

[TRANSLATED BY: FRANCOIS DUMAS] 'No Return Flight' tells about author Haks Walburgh Schmidt's search for the occupants of the Horsa glider 166 that landed near Arnhem on September 18, 1944. The men who set foot on Dutch soil belonged to the British 13 Platoon of the 1st Airborne Border Regiment. A quest that lasted almost 20 years, which eventually led to a poignant image of the Battle of Arnhem. In the fascinating stories from before, during, and after the battle, the human aspect and the personal experience of the soldiers are central. With the 76th anniversary of the Battle of Arnhem, we asked Haks Walburgh Schmidt some questions about his book via email.

Your book tells the story of the 27 men of the 13 Platoon who took part in the Battle of Arnhem in September 1944. What kind of unit was it and what history did it have?

The platoon consisted of 25 men, the other two were the Glider Pilots. The passengers were from the First Battalion, The Border Regiment. That was one of three Battalions, who landed not by parachute, but by glider. Gliders could bring about 25 men to one place at a time. So they could be deployed faster than the Paras who jumped individually and thus landed scattered. Hundreds of gliders were used to fly in soldiers, vehicles, cannons and supplies. The Air Landing troops that arrived by glider were hardly inferior to the paratroopers in combat power. Although that is sometimes the subject of mutual rivalry. To the enemy troops this will not have been an issue, and not so important for younger generations. The Thirteenth Platoon had previously seen action in North Africa, Sicily, and mainland Italy. In England, they participated in an air landing demonstration for Winston Churchill.

It is purely coincidental that this platoon ended up in the book. The reason was the request from Glider Pilot Sergeant Morley Williams if I cared to try and find out who he had flown to Wolfheze in his Horsa with chalk number 166. There is a Horsa in the Overloon war museum. It provides a good impression of how soldiers used the plane and how large and fragile the plywood plane actually was.

What role did the platoon play in Arnhem and did the unit suffer heavy losses during the battle?

Due to engine failure in their tow plane (a C-47 Dakota), the 13 Platoon - and therefore also their Glider Pilots - did not arrive in Wolfheze but on the second day, September 18. They were held in reserve at Battalion HQ and only reunited with their "parent unit", B Company, at Westerbouwing. As part of the defence square that B Company had set up on the Westerbouwing, the 13 Platoon was in position on the steep south side. During the German attack on September 21, the British had to evacuate the hill after fierce fighting. That was a significant loss because it meant that access to the Drielse Veer had been lost and the German troops had a free field of fire on the British perimeter from the Westerbouwing height.

The attempt to launch a counterattack later that day failed with heavy losses on the British side. Members of the 13 Platoon were injured and killed in both actions. Several them also died in the days that followed until the evacuation. Missing to this day are Lance-Corporal Eric Melling and the Privates Telford Fidler and Frank Jarvis. In October 1945, after his captivity, Private John Glenn died in England as a direct result of 'Arnhem'. Some of the survivors died relatively young. A connection with 'Arnhem' is unknown. Of the 25 men who Glider Pilot Morley Williams flew to Arnhem in his Horsa, eight were killed, 13 were taken prisoner (wounded or not) and only four men returned across the Rhine.

Char tank on the Westerbouwing.

Char tank on the Westerbouwing.

You discovered this story thanks to one of the pilots of the glider that landed the men. Who was he and why did he contact you?

I was the one who contacted Glider Pilot Sergeant Morley Williams in 1998. That was for an exhibition by Airborne Museum Hartenstein about the prisoners of war. I got his diary from the museum's archives to produce the accompanying newspaper at "Liberators Behind Barbed Wire", now a collector's item, I understand. In it he told what he had experienced during those days in September and during his imprisonment. When I met him in Oosterbeek a year later, the question arose whether he remembered who he had flown to Arnhem. I then started researching that. Still ignorant of what I would bring upon myself.

Did you manage to get in touch with other veterans in addition to the pilot? And if so, what impressed you most during this contact?

The quest for the other veterans is the core of the book. In the end I had personal contact with five veterans and with relatives of the others. On only one veteran I could not find anything. That of course continues to frustrate me. Most impressive was how people trusted me and what a pleasant and sometimes even friendly bond developed. Frankly sharing stories and old photos of relatives who never returned. Several them met in 2004, when the Dutch version of the book was published. Just have a look at the picture below. In several cases, I was able to show family members around the Westerbouwing, so that they saw with their own eyes where their (grand) father had been and what had happened to him. Impressive and wonderful encounters. It is special to see how the story of Horsa 166 and the Thirteenth Platoon travels through time. From the veteran, through me, to (grand) children of the veteran and then even on to my own children. Not to mention those many people and their relatives who read my book.

Four veterans of the 13 Platoon with author Haks Walburgh Schmidt.

Four veterans of the 13 Platoon with author Haks Walburgh Schmidt.

How did you reconstruct the story? Apart from contact with veterans, what were the main sources?

The research produced a large number of chronological biographies. Which more or less resembled each other. I realized that if I were to paste them together, the list would get boring after the third person. I spent months thinking about how to solve that until I had an idea that resulted in the structure of the book as it is. By far the most important source of the facts was contact with the veterans. This has been supplemented by books, unpublished sources, assistance from British regional and local newspapers and discussions with contemporary experts.

Did you gain a different or deeper insight into the Battle of Arnhem while researching and describing the experiences of the men of this platoon?

To my surprise, the events surrounding the Westerbouwing and thus around the Drielse Veer were not yet described in detail. Even Arnhem veteran Colonel John Waddy remarked that he knew little about what had happened there. Even though the area was of such great importance due to its high location and as a final connection with the south bank of the Rhine. The total situation of the First Airborne Division is not discussed, because the book deals with what happened to the occupants of the Horsa 166. Educational was the response of several veterans to my writer's request for more details. They said that, very understandable and professional, they stayed in cover as much as possible and therefore only were aware of what was happening in their immediate surroundings. Only by combining the personal stories did I get an impression of the bigger picture. Furthermore, it was alarming to discover how hard it was for them during their captivity and how little care there was in the years that followed.

What part of the history you described captured your imagination most and what motivated you to share this story with a readership?

I have long denied to myself that I was one of those tens of thousands of Dutch people who were working on a book. It was not until I got so much new material and even stories about missing occupants surfaced, that I realized I needed to share this knowledge. Various publishers shared that opinion. Most appealing was contacting the veterans or their families and fitting in the information I received from or about them. By taking the Horsa glider as a point of view and by describing the people in Arnhem before their deployment, the reader does not know what happens to an individual person during the fighting. Who will survive, who will be injured or taken prisoner of war. That is different in many other books.

Two veterans of the 13 Platoon are reunited.

Two veterans of the 13 Platoon are reunited.

Is 'The Thirteenth Platoon / No Return Flight' the first book you published? Are you already researching a new book, or will it stop there?

Yes, The Thirteenth Platoon, published in English as No Return Flight, is my first book. Both versions have quite a long history as new facts keep popping up and readers' interest in this history around the world continues to grow. At this time I am not working on a book, but as an independent journalist, I write on a professional basis for newsletters and trade journal articles. That becomes clear when you enter my name in Google.

Tip: There is a TV interview with Glider Pilot Morley Williams on YouTube. The link to it is included in the second English edition of September 2019, the most complete and current version of the book. The Dutch version is the oldest, from 2004. It is only offered by a reseller, without me as a writer noticing anything about it. If you want a signed copy of the radically renewed edition, you can contact me via Facebook and Messenger. For small groups such as reading clubs and the like, I regularly do guided tours of the book.

Your book tells the story of the 27 men of the 13 Platoon who took part in the Battle of Arnhem in September 1944. What kind of unit was it and what history did it have?

The platoon consisted of 25 men, the other two were the Glider Pilots. The passengers were from the First Battalion, The Border Regiment. That was one of three Battalions, who landed not by parachute, but by glider. Gliders could bring about 25 men to one place at a time. So they could be deployed faster than the Paras who jumped individually and thus landed scattered. Hundreds of gliders were used to fly in soldiers, vehicles, cannons and supplies. The Air Landing troops that arrived by glider were hardly inferior to the paratroopers in combat power. Although that is sometimes the subject of mutual rivalry. To the enemy troops this will not have been an issue, and not so important for younger generations. The Thirteenth Platoon had previously seen action in North Africa, Sicily, and mainland Italy. In England, they participated in an air landing demonstration for Winston Churchill.

It is purely coincidental that this platoon ended up in the book. The reason was the request from Glider Pilot Sergeant Morley Williams if I cared to try and find out who he had flown to Wolfheze in his Horsa with chalk number 166. There is a Horsa in the Overloon war museum. It provides a good impression of how soldiers used the plane and how large and fragile the plywood plane actually was.

What role did the platoon play in Arnhem and did the unit suffer heavy losses during the battle?

Due to engine failure in their tow plane (a C-47 Dakota), the 13 Platoon - and therefore also their Glider Pilots - did not arrive in Wolfheze but on the second day, September 18. They were held in reserve at Battalion HQ and only reunited with their "parent unit", B Company, at Westerbouwing. As part of the defence square that B Company had set up on the Westerbouwing, the 13 Platoon was in position on the steep south side. During the German attack on September 21, the British had to evacuate the hill after fierce fighting. That was a significant loss because it meant that access to the Drielse Veer had been lost and the German troops had a free field of fire on the British perimeter from the Westerbouwing height.

The attempt to launch a counterattack later that day failed with heavy losses on the British side. Members of the 13 Platoon were injured and killed in both actions. Several them also died in the days that followed until the evacuation. Missing to this day are Lance-Corporal Eric Melling and the Privates Telford Fidler and Frank Jarvis. In October 1945, after his captivity, Private John Glenn died in England as a direct result of 'Arnhem'. Some of the survivors died relatively young. A connection with 'Arnhem' is unknown. Of the 25 men who Glider Pilot Morley Williams flew to Arnhem in his Horsa, eight were killed, 13 were taken prisoner (wounded or not) and only four men returned across the Rhine.

Char tank on the Westerbouwing.

Char tank on the Westerbouwing.You discovered this story thanks to one of the pilots of the glider that landed the men. Who was he and why did he contact you?

I was the one who contacted Glider Pilot Sergeant Morley Williams in 1998. That was for an exhibition by Airborne Museum Hartenstein about the prisoners of war. I got his diary from the museum's archives to produce the accompanying newspaper at "Liberators Behind Barbed Wire", now a collector's item, I understand. In it he told what he had experienced during those days in September and during his imprisonment. When I met him in Oosterbeek a year later, the question arose whether he remembered who he had flown to Arnhem. I then started researching that. Still ignorant of what I would bring upon myself.

Did you manage to get in touch with other veterans in addition to the pilot? And if so, what impressed you most during this contact?

The quest for the other veterans is the core of the book. In the end I had personal contact with five veterans and with relatives of the others. On only one veteran I could not find anything. That of course continues to frustrate me. Most impressive was how people trusted me and what a pleasant and sometimes even friendly bond developed. Frankly sharing stories and old photos of relatives who never returned. Several them met in 2004, when the Dutch version of the book was published. Just have a look at the picture below. In several cases, I was able to show family members around the Westerbouwing, so that they saw with their own eyes where their (grand) father had been and what had happened to him. Impressive and wonderful encounters. It is special to see how the story of Horsa 166 and the Thirteenth Platoon travels through time. From the veteran, through me, to (grand) children of the veteran and then even on to my own children. Not to mention those many people and their relatives who read my book.

Four veterans of the 13 Platoon with author Haks Walburgh Schmidt.

Four veterans of the 13 Platoon with author Haks Walburgh Schmidt.How did you reconstruct the story? Apart from contact with veterans, what were the main sources?

The research produced a large number of chronological biographies. Which more or less resembled each other. I realized that if I were to paste them together, the list would get boring after the third person. I spent months thinking about how to solve that until I had an idea that resulted in the structure of the book as it is. By far the most important source of the facts was contact with the veterans. This has been supplemented by books, unpublished sources, assistance from British regional and local newspapers and discussions with contemporary experts.

Did you gain a different or deeper insight into the Battle of Arnhem while researching and describing the experiences of the men of this platoon?

To my surprise, the events surrounding the Westerbouwing and thus around the Drielse Veer were not yet described in detail. Even Arnhem veteran Colonel John Waddy remarked that he knew little about what had happened there. Even though the area was of such great importance due to its high location and as a final connection with the south bank of the Rhine. The total situation of the First Airborne Division is not discussed, because the book deals with what happened to the occupants of the Horsa 166. Educational was the response of several veterans to my writer's request for more details. They said that, very understandable and professional, they stayed in cover as much as possible and therefore only were aware of what was happening in their immediate surroundings. Only by combining the personal stories did I get an impression of the bigger picture. Furthermore, it was alarming to discover how hard it was for them during their captivity and how little care there was in the years that followed.

What part of the history you described captured your imagination most and what motivated you to share this story with a readership?

I have long denied to myself that I was one of those tens of thousands of Dutch people who were working on a book. It was not until I got so much new material and even stories about missing occupants surfaced, that I realized I needed to share this knowledge. Various publishers shared that opinion. Most appealing was contacting the veterans or their families and fitting in the information I received from or about them. By taking the Horsa glider as a point of view and by describing the people in Arnhem before their deployment, the reader does not know what happens to an individual person during the fighting. Who will survive, who will be injured or taken prisoner of war. That is different in many other books.

Two veterans of the 13 Platoon are reunited.

Two veterans of the 13 Platoon are reunited.Is 'The Thirteenth Platoon / No Return Flight' the first book you published? Are you already researching a new book, or will it stop there?

Yes, The Thirteenth Platoon, published in English as No Return Flight, is my first book. Both versions have quite a long history as new facts keep popping up and readers' interest in this history around the world continues to grow. At this time I am not working on a book, but as an independent journalist, I write on a professional basis for newsletters and trade journal articles. That becomes clear when you enter my name in Google.

Tip: There is a TV interview with Glider Pilot Morley Williams on YouTube. The link to it is included in the second English edition of September 2019, the most complete and current version of the book. The Dutch version is the oldest, from 2004. It is only offered by a reseller, without me as a writer noticing anything about it. If you want a signed copy of the radically renewed edition, you can contact me via Facebook and Messenger. For small groups such as reading clubs and the like, I regularly do guided tours of the book.

- No Return Flight

- 13 Platoon at Arnhem 1944

- ISBN: 9789059118812

- More information about this book

Used source(s)

- Source: Haks Walburgh Schmidt / TracesOfWar

- Published on: 12-09-2020 14:22:46

Related news

- 02-03: 4,500 crashes in Scotland on more than 700 pages

- 25-02: G.I. Stories 1941-1945 wants to bring the story of the American soldier to a larger audience

- 09-'23: The German Ostheer became bogged down in a war of attrition it could never win

- 09-'23: The men who were written out of the story of D-Day

- 02-'23: ‘The unending journey’ is part of a constant fight against the far-right in all its forms

Latest news

- 28-03: Black pilots had to fight for every step forward

- 25-03: Band of Brothers actors to parachute into Normandy for D-Day

- 02-03: 4,500 crashes in Scotland on more than 700 pages

- 01-03: Kolberg, 1945: Evacuation from a besieged city

- 25-02: G.I. Stories 1941-1945 wants to bring the story of the American soldier to a larger audience

- 28-01: Order a book at Pen & Sword Books and support us

- 27-01: Hitler's last propaganda film premiered 79 years ago

- 06-01: Mike Sadler, desert navigator who guided WWII commandos, dies at 103

- 12-'23: Merry Christmas and a prosperous 2024

- 09-'23: The German Ostheer became bogged down in a war of attrition it could never win