Before the war

Preface

During the Battle of Berlin in 1945, the hospital on the corner of Exerzierstrasse and Schulstrasse in the Wedding district must have looked like any front hospital. While the ground was shaking with grenade strikes and outside the sound of gunfire, doctors and nurses in blood-stained white uniforms did their best to save the lives of the wounded who had been brought in. The only unusual thing was that the medical staff wore a Jew's star, even though the German capital had already been declared free of Jews in 1943

History

Today, the hospital is still in the same place, although the streets are now known as Iranian Strasse and Heinz-Galinski-Strasse. On the tympanum above the former main entrance of the neoclassical style building, the text "Krankenhaus der Jüdische Gemeinde" is carved, as the name of the Jewish hospital originally read. The history of Jewish health care in Berlin dates back to around the 13th century, when the first Jews settled in Berlin and the surrounding area. Poor Jews could go to a so-called Hekdeshfor medical assistance. Originally this was a kind of hostel for Jewish travellers, belonging to a synagogue, but the institution developed into a place for the care of the sick.

After having been the victim of pogroms and expulsion several times in previous centuries, in 1671 Friedrich Wilhelm I, King of Prussia, allowed the Jews to settle in Berlin and the surrounding area. The enlightenment with its ideal of tolerance initiated the gradual integration of Jews into Christian society. Jews began to play an important role in the economic and cultural life of Berlin and their number was to rise to 186,000 in 1933. Construction of the first synagogue in Berlin began in 1712 and in 1756 the first real Jewish hospital was opened on Oranienburger Strasse. The hospital was open to patients and staff of all faiths and provided excellent medical care for the time. With an annual patient count of 400, it was no less than the Charité, the oldest and most prominent hospital in the German capital. That is why the Jewish hospital was also called "the little Charité".

Because the hospital no longer met the requirements of modern medicine, the Jewish community opened a new hospital on Auguststrasse in 1861. It was one of the most modern hospitals in Europe, with treatment and operating rooms on each floor, as well as washrooms with water closets (a novelty). Barely half a century later, this building was no longer adequate either. The Jewish community bought a plot of land in the Wedding district, where the hospital is still located today. Although the location was further away from the city centre, the land was cheap. The hospital with 230 beds opened in 1914, just days before the onset of World War I. The ostentatious neoclassical architecture of the building was proof of the prosperity and pride of the Jewish community. The complex comprised eight buildings, of which the entrance building and main building were the largest. Pavilions and a spacious inner garden gave the building the ambience of a spa. The internal synagogue was proof of the hospital's Jewish identity.

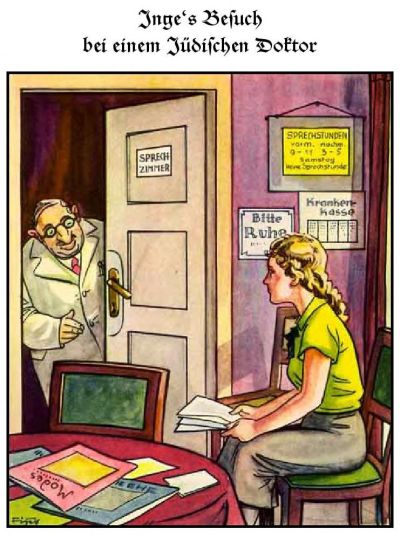

Inge’s visit to a Jewish physician. Two roguish eyes flash from behind glasses and there’s a sneer on his fat lips. With this kind of anti-Semitic propaganda the Nazis tried to prevent Aryans from seeing Jewish doctors. Source: Randall Bytwerk.

Pre-war anti-Semitism

While the Jews of Berlin lived an assimilated existence, anti-Semitism was on the rise again from the end of the 19th century. Hatred of Jews erupted when Hitler came to power in 1933. The consequence for the hospital was that between 1933 and 1938 the number of patients decreased drastically. Although it was not yet forbidden for Aryans to be treated by Jewish doctors, more and more non-Jewish Berliners failed to receive treatment in the Jewish hospital as a result of anti-Semitic propaganda and pressure from the Nazis. In addition, the hospital was no longer allowed to admit patients (even Jewish patients) whose treatment was financed by community funds. In July, only 180 of the 380 beds were still occupied. As a result, doctors and nurses were under-utilized. At the same time, there was an increase in doctors who had been dismissed elsewhere, partly because of the prohibition of 7 April 1933 for Jews to work in the public service (doctors in publicly funded hospitals were also civil servants). Several highly qualified doctors came to work in the Jewish hospital. However, a considerable increase in staff was avoided because several doctors left Germany and emigrated.

It was not until 1938 that anti-Semitic government policy became a real threat to the hospital's survival. In March of that year, the legal status of the Berlin Jüdische Gemeinde (the representation of the Jewish community) was abolished. The Gemeinde, which financed the hospital, had to find other sources of money in order for the hospital in Berlin to survive. These were found, among other things, in the form of donations from Jews abroad. In addition to keeping the hospital financed, the money also managed to keep schools open to Jewish children (who were no longer welcome in public schools) and to provide welfare work for needy Jews.

This sign on the door of a Jewish physician shows that only Jewish patients may be treated. Source: Gedenkstaette Steinhof.

The approximately 3,000 Jewish doctors in Germany were themselves severely affected in 1938. In July of that year their medical license was revoked. This was extended in September with the stipulation that only 700 Jewish doctors were still allowed to practice their profession in Germany, but only with Jewish patients and in Jewish institutions. From then on, they had to call themselves Krankenbehandler (patient handler). The Jewish hospital as a whole was also no longer allowed to admit Aryan patients. Nevertheless, the number of patients would increase until 1941. In 1940, for example, 70% more operations were performed than during the period 1925-1927. The number of patients increased partly because other Berlin hospitals refused to treat Jewish patients, even if they had converted to Christianity. Also, more and more Jewish medical institutions outside Berlin were closed, until only the Jewish hospital in the capital remained. And then there was an increase in the number of Jewish residents in Berlin, because many Jews from smaller communities moved here in the hope that they would suffer less from anti-Semitism. For all these Jews, the hospital was the only place where they could still go for hospital care.

Remarkably, the hospital was spared violence and destruction during the Kristallnacht of 9 to 10 November 1938. However, after that night and the following weeks there was a (temporary) increase in the number of patients. As many as 150 beds had to be added to the surgery department. Several Jews who were injured during the government-orchestrated pogrom had to be treated in the hospital, as were the Jews who returned later that year from a concentration camp where they had been beaten and abused during that outbreak of violence. Especially for Jews who were seriously injured in captivity by the Gestapo or the police, a so-called Polizeistation was set up in the hospital, a closed ward in the main building where between 20 and 80 prisoners could be treated, until they could return to captivity or (from 1941) were healthy enough to be deported.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

First years of war

Beginning of deportations

As a result of anti-Semitism, tens of thousands of German Jews chose to emigrate, until in October 1941 there were 163,000 Jews left of the 523,000 counted by Germany in January 1933. Among the emigrated Jews were several prominent doctors from the Jewish hospital. One of them was Professor Martin Jacoby. From 1907 he had been head of the chemical institute of the Moabit Hospital in Berlin, until he was compulsorily retired at the end of 1933. In 1934 he was able to make the transition to the Jewish hospital, where he was put in charge of a department similar to the one at Moabit. In 1939 his knowledge and experience for the hospital was lost when the professor emigrated to England. Another respected Jewish physician who chose to flee Germany was the urologist Dr Paul Rosenstein, who had worked in the Jewish hospital for many years, since 1923 as head of the surgery department. Brazil was the country to which he emigrated in 1938. Even after 1941, some doctors and nurses of the Jewish hospital managed to leave Germany or go into hiding. Throughout the war the hospital would still have sufficient staff to provide the necessary medical care, but under the supervision of Adolf Eichmann's Jewish Affairs Department of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA, Main Office of State Security).

When emigration was banned in October 1941, more than 70,000 Jews remained in Berlin. Since September of that year they were obliged to wear a Star of David on their clothes. Doctors and nurses in the hospital also wore the star on their white uniforms. The introduction of this stigmatizing symbol heralded the deportations to ghettos and camps in the East, which began in October. At that time, the Jews did not yet know that they would be murdered there. They were told that they would be taken to work camps. The hospital became involved in the deportations in several ways. In the Sammellager (assembly camps that were set up all over Berlin) and at the stations where Jews were put on trains, doctors and nurses had to staff first aid stations. They were also supposed to escort transports, from which they themselves did not return. The emergency workers could not do much more than reassure the victims, but that was exactly why they were deployed. Thanks in part to their presence, panic did not break out and the deportations went smoothly.

Devilish work

Another way in which the Jewish hospital was involved in the deportations was through the so-called Transportreklamationstelle. This committee, set up by order of the RSHA in December 1941, was charged with processing requests for postponement of deportation that Jews could submit on medical grounds. The office of this institution was located in the Schwesterheim (nurse's residence) of the Jewish hospital. Every day from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m., a committee of six doctors, six secretaries and six nurses worked to deal with the many requests submitted. It was a coming and going of patients. Sometimes as many as thirty ambulances would have been at the hospital to deliver sick Jews. "Blind people, the disabled, epileptics and people suffering from tuberculosis were admitted," a secretary from the hospital recalled. "Because of the large numbers, they had to wait standing for hours for their examination. It was most difficult when we had to go through the waiting rooms and we were noticed by friends and acquaintances begging to do something for them, although they themselves knew how powerless we were with regard to this diabolical work".

Jews who met the strict requirements and were found to be ill enough not to have to go on transport were granted a delay of no more than three months. However, many were rejected. Pregnant women, for example, were usually put on transport unless they were about to give birth. Six weeks after giving birth, they were deported with their baby. What also happened was that the sick were treated or operated on, in the hospital to make them suitable for deportation. Much could not be manipulated by the Jewish doctors in favor of patients. The Gestapo exercised strict supervision and called in Aryan doctors for a second opinion to prevent deception. Nevertheless, there are indications that there may have been cheating to delay the deportation of individuals. In 1941, for example, there were remarkably more operations than in previous years. The ophthalmologist in the hospital, for example, performed twice as many operations as his monthly average when the deportations started in December 1941.

The committee was dissolved at the end of 1942. In June of that year, the RSHA in Berlin had started the so-called Alterstransporte (transport of the elderly), in which elderly Jews were transported to the Theresienstadt ghetto in the Czech Republic. Although the location was presented as a model ghetto, where the Jews had a good life, the living conditions were miserable. 89% of the elderly died here or were deported to Auschwitz to be murdered. Now that the elderly were also deported and especially younger and healthy Jews were left behind in the German capital, the committee had become superfluous. Moreover, Jews were no longer allowed to travel by public transport (except for those who lived 4.3 miles or more from their work) and ambulances were hardly available to Jews. This meant that it was no longer possible for sick people to come to the hospital, and the two examining physicians who made home visits were also severely restricted in their freedom of movement.

Suicides

As a result of the deportations, the suicide rate among the Jews increased. The number of suicides rose particularly alarmingly from the turn of the year 1942-1943, when more and more rumours circulated in Berlin about the fate that awaited the Jews after deportation. The fact that nothing had been heard from deported family members, friends and neighbours for months, increased fears among the remaining Jews. In 1942 and 1943, 7,000 Jews were said to have committed suicide in Berlin. There was a well-organized black trade in opiates and other drugs that were lethal in high doses. Especially the tranquilizers Veronal and potassium cyanide (cyanide) were often used by those who wanted to end their own lives. Suicide attempts were not always successful. Those who survived their suicide attempt were treated in the Jewish hospital after which they were put on the transport they feared.

The hospital had to cope with many suicide victims during the time of the deportations. A nurse remembered that the hospital was full of beds on both sides of a hall. "You could barely get past it. Everywhere you put your feet there was a bed with someone who had tried to commit suicide." When there was no room left in the halls and corridors, beds were also placed in the bathhouse. Because of the Hippocratic Oath they took, the doctors were in principle forced to cure the survivors of suicide, but they would nevertheless have left several elderly people to die in peace.

There were also suicides among the hospital staff. One person involved estimated that in the period 1942-1943 fourteen members of staff committed suicide, including at least two doctors. The best-known case of suicide among hospital staff was that of hospital director Dr. Schönfeld. After he had been selected in October 1942 to be put on transport, he and his wife committed suicide in their home. Earlier, a nurse with whom he had a secret affair, had fabricated her suicide. She left behind a syringe and a suicide note in which she wrote that she could no longer cope with her secret relationship with Schönfeld. In reality she went into hiding and survived the war.

Definitielijst

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

Jewish leadership

Herr Dr. Dr.

Just as elsewhere in Nazi dominated Europe, the Jews themselves were deployed in Germany to organise the deportation of their fellow Jews. The body charged with this was the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland, the national Jewish association based in Berlin, which included all the local Gemeinde (communities). When it was founded in 1933, the organization was still called Reichsvertretung der deutschen Juden and since 1935 Reichsvertretung der Juden in Deutschland. After Kristallnacht, however, the illusion that the Jews still had something to say (Vertretung means representation) could no longer be awakened. From then on, the Reichsvereinigung was nothing more than a conduit for Nazi orders to the Jewish community. During the deportations, the organisation was in charge of compiling the transport lists. The Transportreklamationstelle also fell under its responsibility, as did (from 1941) the Jewish hospital (although this responsibility was shared with the Health Department of the Berlin's Gemeinde).

A central figure in the history of the Reichsvereinigung and Berlin Gemeinde and the hospital during the Nazi period was Walter Lustig, born in 1891. He was Jewish according to the Nazi laws but looked nothing like the caricatures of anti-Semitic propaganda. A contemporary described him as very German and, because of his big moustache and Prussian appearance, compared him to "a major from World War I". Autocratic, aloof and arrogant, this is how he was described by others who knew him when he worked in the hospital. He wished to be addressed with Herr Dr. Dr., referring to his doctoral degrees in medicine and philosophy. Some accused the assimilated Jew of being an anti-Semite despite his own origins. In any case, he had converted to Christianity and was married to an Aryan woman. Thanks to this marriage he was protected against deportation during the war years.

Prior to the Nazi era, Lustig was fully committed to the German Empire. During the First World War he served as an army doctor, among others in Breslau where he provided medical care to soldiers returning sick or wounded from the Eastern Front. This was followed by many years of successful careers in the civil service. He rose to become chief of the Medical Affairs Department of the Berlin Police Presidency with the titles Oberregierungsrat and Obermedizinalrat. In this position he came into contact with police officers who would later be employed by the RSHA to supervise the Jewish hospital, such as Rolf Günther, the deputy of Adolf Eichmann.

Lustig's excellent track record was irrelevant when he was discharged in October 1933 because Jews in public service were no longer tolerated. He then worked in the Health Department of the Jewish Gemeinde in Berlin and from July 1939 he was in charge of the same department within both the Gemeinde and the Reichsvereinigung. As responsible for all Jewish medical matters, Lustig also supervised the Jewish hospital and the Transportreklamationstelle. Every postponement of transport issued by the committee was personally checked by him. Within the hospital, he was feared because he closely supervised that the rules and orders of the Gestapo were followed. Perhaps even more notorious was he as a womanizer. He would have had extramarital affairs with several young nurses.

One-man Jewish Council

The fact that the hospital remained open during the war years did not mean that staff were automatically exempt from deportation. In addition to doctors and nurses accompanying transports and not returning themselves, hospital employees were also individually and collectively transported. Among them was the renowned doctor Professor Hermann Strauss. Before the Nazi era he had held a chair in internal medicine at the University of Berlin, and since 1910 he had been chief physician at the Jewish hospital. The professor, who was already in his seventies, was deported in July 1942 to the "geriatric ghetto" Theresienstadt, where he died a few months before the end of the war.

The first collective transport of hospital personnel took place in October 1942 during what has come to be known as the Gemeindeaktion. Because fewer and fewer Jews remained in Berlin, it was no longer necessary to keep the Gemeinde and Reichsvereinigung at full strength. For this reason, 553 employees, together with 328 family members, were deported to Theresienstadt and Auschwitz. Among them were also employees of the hospital, who had been chosen by Walter Lustig by order of SS-Sturmbannführer Günther. It was Günther himself who appointed hospital director Schönfeld, after which he committed suicide and Lustig took over the management of the hospital. In June 1943, the Gemeinde and the Reichsvereinigung were dissolved, although the latter was soon reversed and continued to exist for the rest of the war.

After three top men of the Reichsvereinigung were removed in January 1943, Lustig was the most powerful man in the Jewish community. As leader of the hospital and the remainder of the Reichsvereinigung, which was located in the hospital, he held a position described as a "one-man Jewish Council" from 1943 onwards.

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- ghetto

- Part of a town separated from the outside world to segregate Jewish population. The establishment of ghettos was intended to exclude the Jews from daily life and from the rest of the people. From these ghettos it was also easier to deport the Jews to the concentration and extermination camps. Also known as “Judenviertel” or Jewish quarter.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- propaganda

- Often misleading information used to gain support among supporters or to gain support. Often used to accomplish ideas and political goals.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

Exceptional position

Fabrikaktion

There are several reasons why the Jewish hospital continued to exist after 1942. An important reason was the continued presence of Jews in Berlin who were protected by their marriage to an Aryan or by their partial Aryan origin. In the latter case, there was talk of Mischlinge. Second-degree Mischlinge (or quarter Jews: persons with one Jewish grandparent) were generally treated the same as Aryans. Although fanatics within the Nazi party wanted to treat first-degree Mischlinge (or half-Jews: persons with two Jewish grandparents) in the same way as full Jews, they nevertheless obtained an exceptional position in Nazi Germany, unless such a person adhered to the Jewish religion or was married to a full Jew (such a person was then called a Geltungsjude and considered a full Jew). The reason for these exceptional positions was the fear within the Nazi administration of protests by Aryan family members if their half-Jewish or Jewish relatives were to be deported. In a time of war, resistance within the German people's community could not be used.

Although half-Jews and Jews with an Aryan marriage partner were exempt from deportation, they could not count on equal treatment. It was unthinkable for the Nazis, for example, that Jews would be admitted to the same hospitals as Aryan patients. To offer them medical care, the Jewish hospital remained open. This was partly out of self-interest, because when half-Jews suffered from infectious diseases, they posed a public health risk without medical treatment or hospitalization. For similar reasons, not only the hospital but also the Jewish cemetery in the Berlin district of Weissensee remained open during the war with a handful of Jewish workers. In this way it was avoided that the bodies of Jews had to be buried by Aryans in Aryan cemeteries.

The Jewish hospital continued to have a laboratory and a pharmacy at its disposal. However, the management of medicines was not entrusted to anyone of Jewish descent and was the responsibility of an Aryan pharmacist who remained in service until the end of the war. He was the only remaining non-Jewish staff member after the faithful Aryan midwife was no longer allowed by the Nazis to remain in the service of the hospital.

On February 27, 1943, it seemed as if the former Jews who had been exempt from transport were no longer safe. Approximately 1,800 privileged Jewish men were then arrested and imprisoned in a building of the Jewish community at Rosenstrasse 2-4. Their Aryan wives or mothers gathered in front of the building and demanded their release. This happened on 1 March and it was probably never the intention to put these men on transport. They probably wanted to temporarily isolate them from non-privileged Jews, of whom about 10,000 were rounded up and deported to Auschwitz. Because most of these Jews were arrested in the factories where they performed forced labour, the operation went down in history books as Fabrikaktion. The deported Jews also included hospital staff and patients.

Lustigs list

Shortly after the Fabrikaktion, fate struck again for the hospital residents in March 1943. On the street in front of the hospital several arrest vehicles stopped on March 10. A group of Gestapo and Kriminalpolizei officers entered the hospital and ordered Lustig to evacuate the hospital. Lustig, however, refused to cooperate as long as there was no official order from Eichmann's office. Apparently there had been a misunderstanding between different departments of the SS. Shortly afterwards, three other SS officers, including Fritz Wöhrn, who supervised the hospital, ordered Lustig to select half of his personnel plus their relatives for transport the next morning.

Lustig and his secretaries worked all night to compile the list. Unmarried full-Jewish men ran a great risk of being chosen, while indispensable doctors and nurses were kept off the list. The next day the Jews on the list were taken to a Sammellager in Berlin, from where they were deported to the extermination camps in the East. Lustig was hated by most of the Jews in the hospital because of his cooperation in the transport and they accused him of treason. However, he did not appear to have been a willing collaborator of the Nazis. On the contrary, several Jews owed their lives to him. When another Gestapo raid on the hospital followed in May 1943, the Gestapo people had compiled their own list. When his secretary was taken away and ended up in a Sammellager, he took her out personally, together with ten or fifteen others.

Another dramatic moment in the history of the hospital also took place in 1943, namely in June. Then the last remaining residents of Jewish nursing and old people's homes were deported to Theresienstadt, including the residents of the nursing home connected to the Jewish hospital. The bedridden patients were warmly dressed by staff and given clean underwear, shoes and a warm blanket. Many were put on diapers, which often had to be changed quickly due to all the stress. When the preparation of the elderly took longer than the allowed two hours, the Gestapo ordered Lustig to hurry. How it turned out with these needy people in the end, can be guessed.

Definitielijst

- Gestapo

- “Geheime Staatspolizei”. Secret state police, the secret police in the Third Reich.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

Patients and staff

Bastion of life

From 1942 until the end of the war, a motley company stayed inside the hospital walls, consisting of hospital staff, patients and various other residents. At the end of the 1943 deportations, the hospital had 60 staff members, including doctors, nurses and support staff, who all lived on the hospital grounds. Many of these staff members had lost their own homes during bombardments. In addition, there were 24 other staff members on the payroll who stayed elsewhere, including a number of Mischlinge who were employed here after the Fabrikaktion. One of them was Günther Rischowsky, who had been chosen by Lustig himself, together with his brother, as site manager, while his brother was appointed as an autopsy assistant. "We worked as well as we could, more than we were expected to," Günther explained. "We were aware that the hospital symbolized a bastion of life. We worked wherever we were assigned, be it in the children's ward, in the garden, as roofers, nailing window frames, as room assistants or as elevator boys".

The spacious inner garden imparted the atmosphere of a spa to the hospital complex and was partially converted into a kitchen garden during the war. Source: Jüdisches Museum Berlin / Yad Vashem.

Patients from 1942 onwards, included psychiatric patients from evacuated Jewish psychiatric institutions elsewhere in Germany. These were mainly foreigners who had been spared for the time being because of their non-German origin, while most Jewish psychiatric patients in Germany had already been transported with their caregivers to the extermination camps. A psychiatric ward with 120 beds had been opened especially for them. The psychological care provided was insufficient: there was no trained staff, no special medication and psychological treatment was limited. In order to give the patients a meaningful day care, they did chores in and around the hospital. It was a heavy blow when, over time, the Gestapo forbade them to leave their rooms and walk in the garden.

At the end of 1943 the privileged position of foreign psychiatric patients in the hospital came to an end. Because no foreign government had responded to the Gestapo’s demand of 31 July 1943 to protect their subjects, the foreign passports were revoked and on 21 November 1943 the entire psychiatric ward was evacuated. All patients were executed in the forest near Sachsenhausen concentration camp, near Berlin.

In 1942, dozens of Jewish orphans also arrived at the hospital in Berlin after their orphanages were closed. The hospital already had a children's ward, but also opened a Kinderunterkunft, a children's home. The hospital staff could not prevent the deportation of orphans whose full-Jewish descent was undeniable, but managed to spare the children whose father's Jewish identity had not been proven. The social affairs department of the Reichsvereinigung was especially concerned with tracing evidence of the father's Aryan ancestry, such as birth certificates and baptismal records. Approximately sixty orphans between the ages of six and eighteen survived the war in the hospital.

Vips

During the last years of the war, the hospital also housed some Jews who were privileged, because of their former position. Some of these "VIPs" stayed at the Polizeistation, including Dr. Arthur Eichengrün, who discovered aspirin as a chemist for the German Bayer concern. Because of his marriage to an Aryan woman he was exempted from deportation. He had even managed to remain employed by Bayer after the Nazi takeover. It was only when he failed to add the name Israel, which was compulsory for Jews, to a patent application, did he come to the attention of the authorities. He was arrested for this offence. After he became ill following his arrest, he was transferred to the hospital police hall. After his recovery he was deported to Theresienstadt, where he survived the war.

Most VIPs stayed in the department known as Extrastation (special department). Several privileged Jews lived here in furnished private rooms. Two of the residents were the former Minister of Justice Eugen Schiffer, converted to Christianity, and his unmarried daughter. The old-excellency was a familiar sight in the hospital: he strolled through the garden every day, even when it rained. He and his daughter survived the war. The reason for their survival is unknown, but they may have had an unknown protector with a high position within the government.

The identity of other residents of the special department is somewhat shrouded in mystery. Some members of the wealthy Jewish Rothschild family are said to have stayed here, as well as a Frau Oppenheimer, also from a wealthy Jewish family. It is remarkable that one of the residents was confined to a wheelchair during the war, but turned out to be able to walk after the liberation. Another occupant worthy of mentioning was an elderly woman who was regularly visited by SS officer Walter Dobberke, the chief of the Sammellager that had been stationed on the hospital grounds since 1944. The elderly lady was the mother of a childhood friend of the SS officer.

Collegial cooperation

During the last years of the war, the hospital was overcrowded. This was because part of the buildings had been confiscated and every remaining piece of space was used as living space for the staff and other Jews who had moved here. Already in 1942, the Reichsvereinigung was forced to hand over the hospital complex to the German Akademie für Jugendmedizin, but this educational institution would never settle here. This was partly due to the fact that parts of the hospital were used by the Wehrmacht and later also as a Sammellager. These destinations were considered more important than the academy and the hospital profited from this.

It was the gynaecology department, the operating room, the nurses' quarters and the infection ward that were confiscated by the German army to serve as a field hospital (Feldlazarett No. 147). The Jewish hospital was therefore forced to set up an operating theatre and nurses' quarters elsewhere, but benefited from the presence of the army. Both the central heating and the electricity connection were shared with the Feldlazarett. While German citizens in the surrounding district suffered from cold and often had no electricity, in the hospital the heating was on and most of the time there was electricity. Also notable is the collegial cooperation between the Jewish doctors and the German army doctors. Medical supplies were shared and Jewish workers who carried out chores in the Lazarett were usually given something extra to eat. Through the staff of the army hospital and local residents, the Jews in the hospital were also aware of the German defeat in Stalingrad in February 1943. It gave them courage, but the liberation would take another two years.

The department of gyneacology of the Jewish hospital in 1935.This was one of the department used by the Wehrmacht as a field hospital during the war. Source: Jüdisches Museum Berlin / Yad Vashem.

Small Island

"A small island ... cut off from the rest of the world", that's how the Jewish hospital in Berlin was called by a survivor at the time of the war. Patients, staff and other persons present left the hospital grounds as little as possible from the moment deportations took place to avoid arrest. However, they were not entirely safe in the hospital either, because the dreaded Fritz Wöhrn regularly came for an inspection and could then designate any person and send him on a transport. Once he had a Jewish woman deported because she was not wearing her Star of David. Adolf Eichmann would also have been a regular guest at the hospital.

The Jews in the hospital constantly lived between hope and fear, but at the same time ordinary life continued. Friendships, relationships and quarrels arose, just as in any other community. Nurses escaped the curfew of 10 p.m. and left the building through the outside door of the kitchen in the basement for a romantic meeting or gathering with friends in the garden. After the Jews were no longer allowed to visit cinemas and theatres, a theatre group was established in the hospital. There was also a choir in the synagogue, consisting of nurses and doctors. After all religious services were banned by the Nazis in 1942, religious Jews only met in secret to profess their faith.

The synagogue (see the Star of David in the window frame) was proof of the Jewish identity of the hospital. Source: Jüdisches Museum Berlin / Yad Vashem.

The livelihoods of patients, staff and other persons who had a permanent residence in the Jewish hospital were paid for during the war years by the RSHA and the patients or their insurance. Because more and more food, including milk, butter, meat, eggs and fresh fruit, was no longer allowed to be sold to the Jews and rations became ever smaller, food was scarce and one-sided. In the end, the daily diet consisted mainly of potatoes and coarse bread, which was difficult for patients with stomach problems to digest. In order to provide the hungry hospital residents with something more varied, a large part of the hospital garden was plowed and used as a vegetable garden. At one point, cows from a dairy farmer in the neighbourhood would also have found a safe haven in the garden. The freshly milked milk was a healthy and nutritious addition to the daily hospital ration.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

- synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

- Theresienstadt

- City in the Czech Republic. Here the Nazis established a model concentration camp.

- Wehrmacht

- German armed military forces, divided in ground forces, air force and navy.

Last Year of War

Sammellager

While Joseph Goebbels as Gauleiter of Berlin declared that Berlin was Judenrein on May 19, 1943, thousands of Jews still resided in the German capital. These included Jews from mixed marriages and the Jews in the hospital, but also those in hiding. After all other assembly camps were closed, all transports took place from February 1944 onwards from the Jewish hospital, where the pathology department was set up as a Sammellager. Small transports to Auschwitz took place until the autumn of 1944. SS-Hauptsturmführer Walter Dobberke, a former policeman, was in charge of the assembly camp that was closed off from the rest of the hospital grounds with barbed wire. Although it was strictly forbidden for Aryans - and therefore certainly for SS officers - to maintain intimate relations with Jews, he had a secret relationship with a nurse at the Jewish hospital. Apparently the man had a mild side, as he would have warned the Jews in the hospital on more than one occasion of an impending raid.

Buildings in Berlin on fire after an allied bombardment. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J30142 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

During the last year of the war, the Sammellager was also the residence of the so-called Greifer, Jewish collaborators of the Gestapo who were involved in tracing and arresting Jewish people in hiding. Most notorious was Stella Goldschlag, a handsome blonde Jewess who may have betrayed hundreds of Jews in Berlin. It was a colleague of hers who arrested a young Jewish woman at an S-Bahn station in August 1944, who had jumped in front of an approaching train to escape arrest. With a crushed foot she was taken from under the train and taken to the hospital. It was none other than Doctor Lustig who took care of much of the treatment. Every day he visited his patient to remove the bone fragments from her foot and then wash and reconnect the foot. Normally her foot would have been amputated, after which she would have been put on the next transport to Auschwitz, but Lustig may have wanted to spare her this fate. A Gestapo officer, who had himself studied medicine for several semesters, gave his approval and found it an interesting experiment. For months the woman suffered terrible pain and could not get out of bed, but she survived the war.

City in ruins

Besides the Jews in the hospital fearing deportation every day, there was another danger that threatened them from the air. The Allied air forces carried out a total of 363 bombing missions on Berlin during the war years. At least 20,000 civilians lost their lives and many more were injured or left homeless. Industrial targets in the vicinity of the hospital were also frequently targeted by heavy bombardments. Especially during the last year of the war, the bombardments were heavy and frequent. While an increasing part of the city turned into rubble, the hospital was spared the worst. The complex suffered damage mainly from the air pressure from explosions close by and flying debris and shrapnel, but it was strikingly not directly affected. Once, during a bombardment, forty craters were struck in the courtyard garden, but in spite of this everyone remained unharmed.

While an increasing part of the city was turned into rubble, the Jewish hospital was spared the worst. Source: Imperial War Museums.

The fact that the hospital survived the war almost unscathed was not only a matter of luck, but also thanks to the efforts of the Jews who stayed here. They had a great interest in keeping it habitable. "We had to protect our hospital as best we could," said one of them. "If the hospital hadn't been there, we wouldn't have been here. They wouldn't have put us in a hotel or something." Because they didn't have to count on the authorities - who refused to help Jews - they set up their own air guard and fire brigade under the direction of the chief of technical services. A former firefighter, who stayed in the hospital as the Jewish husband of an Aryan woman, trained hospital staff in fighting fires.

Every night a changing team of young men kept watch on a wooden observation platform on the roof of the main building. As bombers raced over with their deadly cargo, they removed fire bombs and burning debris from the roof before more damage could be done. As a reward for the life-threatening work, the night watchmen were given a large sip of alcoholic beverage after their shift, which was manufactured in the pharmacy. The work had not yet been done, because the bomb damage had to be repaired. Holes in the roof were repaired using material collected in the ruins of bombed houses. Wood and even cardboard was used to seal the windows from which the window panes had broken. In this way it was possible to keep a large part of the buildings habitable. Only a few parts had to be evacuated due to damage.

A consequence of the bombing of Berlin during the last phase of the war there was a further increase in the number of people staying on the hospital grounds. When Jews who, thanks to their protected marriage, were still in the city lost their homes in a bombardment, the Reichsvereinigung placed them in the hospital. All those hospital residents camped in the basement under the building complex during bombardments. Initially, bedridden patients were only brought down in the event of an air alarm, but during the last months of the war they stayed there constantly, because bringing them back and forth was impractical due to the increased frequency of the bombardments. Once Aryan residents realised that the hospital had withstood every bombardment miraculously, they too sought a safe haven during air raids. In order to isolate them from the Jews living there, the Gestapo appointed a special section for them in the basement.

Red Army soldiers during the battle for Berlin. During the last days of the fighting, doctors in the Jewish hospital courageously continued treating their patients.

For one group of residents of the hospital, the bombing represented the greatest risk, namely the patients in the Polizeistation. Although their shelter was on the top floor, and they would therefore be the first to be hit by a bombing, they were not initially allowed to leave their closed ward to find a safe haven with the others in the basement. Later, when the bombing increased in intensity during the war, permission was given. Officially, however, permission had to be obtained from the Gestapo each time by telephone. That took so much time that the patients were not down in time. Eventually, employees of the Reichsvereinigung decided to evacuate the police department without permission when the alarm sounded. Because no disciplinary measures were taken, they continued this practice for the rest of the war.

Battle of Berlin

While the last deportations had taken place from Berlin to Auschwitz last autumn, at the end of February 1945, according to an official census by the Gestapo, 6,284 Jews still lived in the German capital. Of these, 162 were "full Jews" who were not protected by a mixed marriage. Most of this group worked in the hospital and owed their survival to it. However, the struggle for survival of those who remained in the hospital was not yet over. As the Red Army approached the German capital closer and closer, they feared that their privileged position could come to an end at any moment and that they would be executed at the last minute. However, when the Battle of Berlin broke out in April 1945, the Jews in the hospital were still unaffected by the SS.

Hospital ward in 1935. In the last weeks of the war, things would have looked a lot more chaotic. Source: Jüdisches Museum Berlin / Yad Vashem.

It is not entirely clear why the Jews in the hospital were spared even during the final phase of the war. SS officer Dobberke, the commander of the Sammellager on the hospital grounds, would have been ordered to execute the Jews, but he failed to do so. According to some survivors, his mistress, a nurse from the hospital, managed to persuade him to do so. Before he took off with her on 24 April, he is said to have had his prisoners sign a statement saying he had spared their lives. By doing so, he hoped to escape allied persecution (he would die of diphtheria in a Soviet prisoner of war camp in 1946). The other guards and the Jewish Greifer also left the hospital grounds around the same time. Previously, the Gestapo had burned incriminating documents in the incinerator of the hospital.

During the last days of the Battle of Berlin the doctors at the hospital bravely continued to treat patients, while outside the hospital the sounds of artillery fire and gunshots were heard. Although this had been forbidden under Nazi law since 1938, desperate and wounded Aryan citizens also sought help in the hospital, which they were not refused. Among the wounded who were treated at the time was also at least one Jewish soldier from the Red Army. The conditions in the hospital were appalling. All rooms were overcrowded with wounded, sick and healthy residents. The power had gone out, so that extra lighting had to be provided during operations with oil lamps. Replenishing the ever dwindling water supply was life-threatening. The water source was in the open air on the hospital grounds, where water carriers were exposed to snipers and flying shrapnel, bullets and debris.

As a result of unhygienic conditions and limited medical care, relatively more patients died during the Battle of Berlin than during previous years. A total of 567 people died in 1945, which was 22% of the total number of patients of that year. In 1943 this was 29% (425 deaths) and in 1944 more than 17% (124), while in the pre-war period this percentage fluctuated between 8.6% and 15.8%. Despite the risk of being shot at or hit by an artillery attack, the dead were buried in the hospital garden during the last days before the end of the war. They would later be reburied at the Jewish cemetery Weissensee.

Definitielijst

- brigade

- Consisted mostly of two or more regiments. Could operate independently or as part of a division. Sometimes they were part of a corps instead of a division. In theory a brigade consisted of 5,000 to 7,000 men.

- Gauleiter

- Leader and representative of the NSDAP of a Gau.

- Gestapo

- “Geheime Staatspolizei”. Secret state police, the secret police in the Third Reich.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

Liberation and beyond

Juden kaputt!

"Nichts Juden. Juden kaputt!" Those were the words of a Soviet soldier who entered the Jewish hospital on April 24. The SS had left the hospital grounds earlier that day and the Jews were relieved that the Red Army had finally arrived. When a representative of the hospital explained to the military that most of the people present at the hospital were Jewish, the man could not believe it. After all, he had heard about the mass murder of the Jews and found it inconceivable that there were still Jewish survivors in the centre of the Third Reigh. In fact, there were far more than the 800 to 1,000 in the hospital. In total, Berlin still had about 8,000 Jewish survivors, mainly Jews from mixed marriages and about 1,700 people in hiding. Of the 70,000 Jews who had lived in Berlin in 1941, approximately 55,000 had been deported to concentration and extermination camps during the war. Only 1,900 of them would return alive. The rest committed suicide, fell victim to war violence or died of illness.

Soldiers of the Red Army celebrating victory in Berlin. In the Jewish hospital between 800 and 1,000 Jewish survivors were found. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-E0406-0022-018 / CC-BY-SA 3.0.

In poor Russian, the Jews in the hospital were eventually able to convince the Red Army of their Jewish identity. The Soviet soldiers then left them unaffected, while they took all staff and patients of the Lazarett prisoner of war (which, however, remained in the same place for the time being). The arrival of the Soviet army did not lead to a festive mood in the hospital, although probably no Jewish women were raped (which happened to many Berlin women). Undisciplined Mongolian troops stole jewels from patients. Better disciplined troops later did their best to return the loot. The battle for the German capital had not yet ended either. In the hospital garden the Soviets housed a field artillery unit. What was left of the rose bushes in the garden was eaten by the horses of the Red Army. Due to a shortage of ammunition, the hospital was no longer in the German line of fire, but outside the gates of the hospital fights were still taking place and snipers were lurking.

The food supply at the hospital was perilous. There was meat, after the Red Army donated a pig to the hospital. The fact that the meat was not kosher made no difference to most of the starving Jews in the hospital. In order to be able to keep feeding all the mouths, a group of Jews performed a daring operation. With false identification cards and Red Cross bracelets, the Jews visited a nearby bakery, where they pretended to be employees of the Lazarett and, thanks to this deception, were given bread. On their way back, however, they were stopped at an SS command post. The SS didn't trust it and were about to shoot the Jews on charges of espionage when the commander of the Lazarett called them. The man had been informed by Lustig and managed to free the Jews. When they returned, both the Jews in the hospital and the German soldiers in the hospital were able to benefit from the bread.

Relief and recovery

On 2 May 1945, war violence stopped in the vicinity of the Jewish hospital. A period of 12 days and 11 nights of uninterrupted living in the basement by the Jews came to an end. It must have been no less a relief that after all these years they were finally able to take off their star and regain their freedom. On 8 May 1945, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel signed the German capitulation at the headquarters of the Red Army in Berlin and the Third Reich came to a definitive end. For the approximately 10 remaining doctors and about 20 nurses in the Jewish hospital there was a busy time. While 245 admissions were counted in the first four months of 1945 (it is unclear whether the wounded were counted during the Battle of Berlin), there were 2,319 during the rest of the year. This increase was caused by Jewish survivors from the camps who were hospitalized in a weakened condition.

In the reception of the repatriated camp prisoners, help came from unexpected quarters. An army doctor, who had escaped from captivity and was left behind in the deserted Lazarett, was in charge of the triage. Victims with tuberculosis, typhoid fever and other serious illnesses were, under his leadership, separated from the patients who were in less dire straits. Despite the shortage of beds, medicine, food, and other necessary supplies, the hospital seemed to have barely needed time to recover from the chaotic last months of war. A 22-year-old camp survivor, who returned to Berlin with other survivors in August 1945, was amazed at how organized he found the hospital. "The city had been destroyed, buildings had been bombed to the ground", he remembered. "We walked to the hospital, which was not damaged. I was surprised that it looked as if nothing had happened, time stood still. A Jewish nurse in a clean, starched uniform greeted us and took us to a room with clean beds […]. "

On 11 May 1945, the first post-war birth took place in the hospital. It was a child of Christian parents. That same day, a Jewish religious service was performed in the hospital synagogue for the first time by a rabbi from the Red Army. About a year later, on June 3, 1946, the synagogue was festively reopened. During a ceremony the original Torah scrolls were carried inside. A notable absent from this event was the former hospital director Walter Lustig. Shortly after the liberation he was appointed by the Soviet authorities as director of Health Affairs for the Wedding district and leader of the post-war Reichsvereinigung. Nobody was surprised when one day in June 1945 he was picked up by two Soviet officers in a limousine, apparently for an meeting with the occupying authorities.

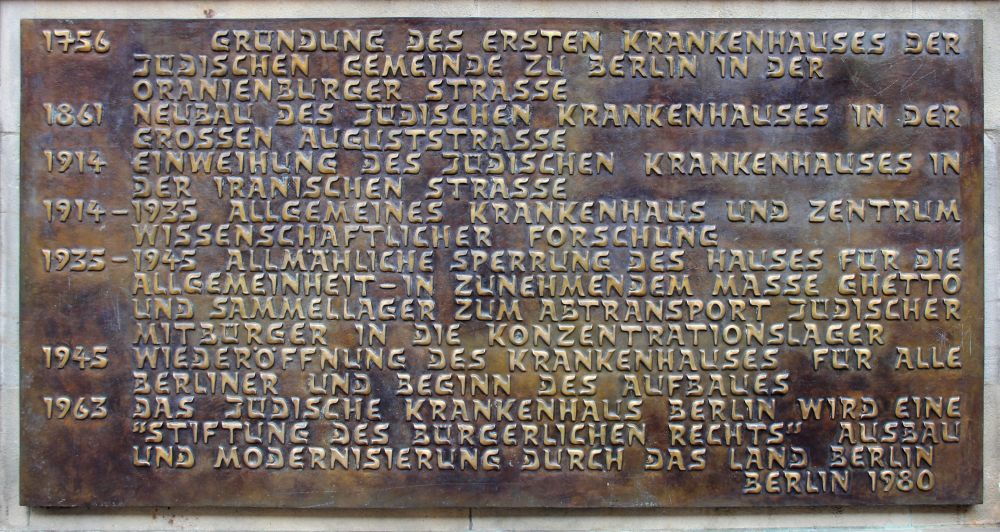

This bronze sign records the most important events in the history of the hospital. This memorial is located on a wall near the present main entrance on Heinz-Galinski Strasse. Source: OTFW / Wikimedia Commons.

Lustig, however, would never be seen again. According to most sources, he was transported by the Soviets to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, which they used as an internment camp. There he would have been executed without trial, possibly because he was accused of collaborating with the Nazis. It is unclear why the Soviet authorities had appointed him sooner or in a high position. When his wife applied for a widow's pension, the district court in Berlin declared her husband dead on December 31, 1945. Opinions differ as to whether he really was a pawn of the Nazis or whether he did his best to do what he could for his patients and hospital staff. After the war, the Berlin Jews did not have a good word for him, but because of his sudden disappearance, he was never able to account for the controversial role he played during the war.

Multicultural

Today, more than 70 physicians treat about 20,000 patients a year in the Jewish hospital, which was renovated and expanded in 1970. As the only Jewish institution, apart from the Jewish cemetery in Weissensee, that survived the Nazi era, the so-called Jüdisches Krankenhaus Berlin symbolizes the highs and lows of the Jewish community in Berlin. Visitors are greeted at the entrance by a bust of Heinz Galinski, the first president of the post-war Zentralrat der Juden in West Germany, the successor to the Reichsvereinigung. As the most important representative of the Jewish community in Germany, Galinski played a decisive role in the reconciliation between Germans and Jews. For visitors who want to learn more about the history of the hospital, a permanent exhibition has been set up. The most important historical events are also listed on a bronze plaque on a wall outside, near the main entrance.

The hospital still has a Jewish identity. Some Jewish doctors work there and in 2003 the renovated synagogue was reopened. Currently, however, only about 10% of the patients are Jewish. Nowadays the surrounding area has a multicultural character and many patients are Muslims of Turkish or Arab descent. The hospital management is proud of its open character and is inspired by its rich history. "We [...] see ourselves as successors and perpetuators of the long-standing medical tradition," declared hospital director Dr. Jechezkel Singer in 2007. "For many centuries, the Jewish community in Berlin was convinced that a community is there to help the sick and the weak. In Judaism, tzedakah (charity) and bikur holim (visiting the sick) are among the most important duties of communal life".

Definitielijst

- capitulation

- Agreement between fighting parties concerning the surrender of a country or an army.

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Judaism

- Monotheistic religion developed among the ancient Hebrews.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

- synagogue

- Jewish house of prayer.

Information

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Translated by:

- Fernando Lynch

- Published on:

- 16-04-2020

- Last edit on:

- 21-04-2020

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related books

Sources

- MOORHOUSE, R., Berlin at War, The Bodley Head London, Londen, 2010.

- SILVER, D.B., Refuge in Hell, Mariner Books, New York, 2004.

- WYDEN, P., Stella, Anchor Books, New York City, 1993.

- Siegel-Itzkovich, "A hospital with history", The Jeruzalem Post, 23-06-2007, op: www.jpost.com.

- Jewish Community of Berlin

- Jüdisches Krankenhaus Berlin