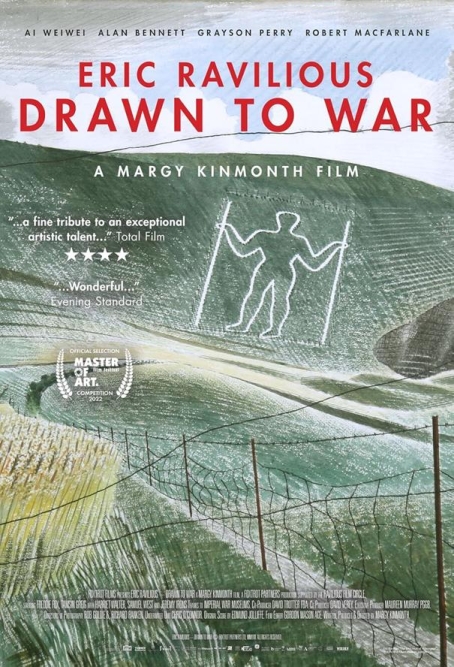

| Title: | Eric Ravilious: Drawn to War |

| Director: | Margy Kinmonth |

| Released: | 2022 |

| Production: | Foxtrot Films Ltd |

| Playtime: | 87 minutes |

| Description: | “I find it hard to say what it is to be English, but Ravilious is part of it.” These words by British author and actor Alan Bennett are about painter Eric Ravilious (1903-1942). He spoke these words in the documentary Eric Ravilious: Drawn to War from 2022. In this production by the British director Margy Kinmoth, the career and the work of the English painter are being discussed. Besides his work as a landscape painter, wood-engraver, and illustrator, he became known for the watercolours he made as a war artist during World War II. The DownsEric William Ravilious was born on July 22, 1903 in London, but he spent most of his youth in Eastbourne in Sussex. From a young age, he already enjoyed going out to the Downs, the chalk hills along the South East coast of England, of which he then made his first drawings. Many of the works he made in his adulthood have also been inspired by this distinctive hilly landscape. “He always kept coming back to the Downs”, says author and Ravilious connoisseur James Russell in the documentary, “and I think partly because he knew it better than other people, so he knew where to go to find the best subjects”. Ravilious’ oeuvre includes, among other things, his watercolours and wood-engravings on which the Long Man of Wilmington can be seen. This human figure made out of chalk with a length of almost 69 meters is located on a ridge near Wilmington in East-Sussex. At some point, mankind thought this huge eyecatcher was from the Iron Age or even earlier, but nowadays it is assumed that it was made in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. English countrysideRavilious was admitted to the Royal College of Art in 1922, where he was greatly inspired by his teacher Paul Nash (1889-1946) who was a skilled wood-engraver besides being a painter. Ravilious’ teacher became partially known for the oil paintings which he made during World War I as a ‘war artist’ at the front of Flanders. After serving as a regular officer in the surrounding area of Ieper, the British War Propaganda Bureau appointed him an official war artist in 1917 and assigned him the task to document the battle in his art for future generations. Perhaps his most important painting, ‘We Are Making a New World’ from 1918, shows a surrealistic landscape of craters and broken tree trunks with in the background a sun breaking through from behind a hill. In both Ravilious’ prewar works and the works he made during the war, there are some recognisable signs of his inspirator, but he did develop his own, recognisable style that looks more cheerful than Nash’s work. Ravilious’ prewar landscape watercolours show the calmness of the English countryside in a style that fluctuates between modernism and realism. Besides landscapes, he also painted everyday scenes, such as the interior of cottages, shopfronts, and vehicles. Eileen Lucy ‘Tirzah’ Garwood (1908-1951), who he married in 1930, is depicted in several of his works. She herself was also a talented painter and wood-engraver. The couple had three children, of whom daughter Anne Ullmann shares her memories in the documentary. These memories are not just positive, because the extramarital affairs Eric held hurt his wife deeply and he was greatly embarrassed about his actions afterwards. Granddaughter Ella Ravilious, who works as a curator at the Victoria and Albert museum in London, tells about the works of her grandfather, which she describes as cheerful. According to her, you see “it’s really him enjoying things, and painting them. I get that sense from his work that that’s how he was as a person.” In the documentary, different examples of his works are being shown, also including his assignments for commercial companies, such as the ‘alphabet mug’ of Wedgwood with an illustration at each letter (I for Indian, J for jar, K for kettle, etc.). München 1938In the documentary, some current artists speak about the works of Eric Ravilious. Grayson Perry praises his ability to make “master pieces” of “fairly unprepossessing subjects”. He emphasises how difficult it is to work with watercolour, because “you’ve got no second chance with it”. According to him, Ravilious had to be “incredibly confident to be able to paint like that. Very, very skilful.” The earlier mentioned Alan Bennett is also an admirer, although he does remark that the artist was not that good at drawing cars. According to him, he painted them “a bit boxy”, like toy cars. Another work, ‘Tea at Furlongs’ from 1939, is described by Bennett as “slightly ominous.” A small table with two chairs underneath a parasol in a walled garden can be seen, with rolling fields and acres behind it. The table is set and the tea is ready, but there is no one in sight. According to Bennett, there is a feeling that something is going to happen and therefore, he claims the painting also could have been named München 1938, a reference to the conference in the German city a year earlier that should have guaranteed peace with the Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia as ‘collateral’ for Adolf Hitler. The British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain preached after his return from München that he had achieved “peace for our time”, but in September 1939, Germany invaded Poland and a new World War began, which would also have big consequences for Eric Ravilious. He was initially sorted into the Royal Observer Corps, which was tasked with tracing and identifying enemy aircrafts in British airspace. The work consisted of staring at the sky for hours, and Ravilious found it to be depressing. At the same time, he also found it exciting, as revealed in a letter he wrote to his wife: “I work at odd hours of the day and night watching aeroplanes up on the hill […]. It’s like a boy’s own paper story, with the spies and passwords and all mater of nonsense. […] We get Germans over from time to time and then, of course, it’s a buzz of activity and excitement.” Childlike innocenceAt the suggestion of Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery in London, from 1939 onwards, artists were appointed to be sorted into the armed forces to capture the war in their art, just like during World War I. On Christmas Eve 1939, Eric Ravilious was appointed war artist and he was assigned to the Royal Marines. He received a uniform and the honorary rank of Captain. Instead of the familiar landscapes, he painted things like warships, Spitfires, and fortifications from now on. His works do not show the horrors and bloodsheds of the war, but the aesthetics of the modern military technology which was used in the battle against nazi-Germany. The Chinese artist and human rights activist Ai Weiwei, who made a large painting titled History of Bombs covering both the floor and wall in the Imperial War Museum, tells in the documentary that Ravilious made the war in his works “less dramatic”. He describes a watercolour painting of the aircraft carrier HMS Glorious in the Arctic which Ravilious made in April 1940 as a “little bit romantic, the colouring and the light, even the airplane”. According to him, the work does not trigger any fear and it is not bloody, but rather “a bit like a fairytale” and depicts a “childlike innocence”. Nevertheless, the horrors of the war kept approaching the English artist, because on June 8, 1940, the Germans ships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau sank the HMS Glorious, which he had painted earlier, which caused the death of 1.200 crew members. Amid the tension and insecurity, Ravilious kept seeing the beauty in both the landscape and human creations. For example, he was impressed by the midnight sun and the colours of the seawater during his stay in the Arctic. “The seas in the Artic Circle are the finest blue you can imagine”, he wrote to his wife, “an intense cerulean and sometimes almost black”. He was just as much fascinated by the technology and interior aboard the submarines in which he sailed along and of which he captured his impressions with his pencil. The pleasure he had in painting never waned, but during wartime it also added a feeling of responsibility which is described by Charles Saumarez Smith, former director of the National Portrait Gallery and National Gallery in London, in the documentary in the following manner: “What drew Ravilous to war was that sense of the world changing. Actually, they [the war artists] were part of the war effort and that must have given them a strong sense of responsibility.” Beloved artistOn September 1st, 1942, Ravilious wrote from Iceland in a letter to his wife that it was freezing. “The weather is deteriorating, rough and windy and rainy.” Nevertheless, he enthusiastically shared that he had received the offer to join a flight in an aircraft that would be searching for a missing American military airplane. He ended the letter with kisses for the children. The search took place a day later but Ravilious would never return. The artist and the four-headed crew of the British aircraft were never found. “I’m sorry that the visit of Captain Ravilious to Iceland has ended so tragically”, wrote the commanding officer to Ravilious’ wife. “From the artistic side, his loss is really deplorable and he will be quite impossible to replace.” Tirzah herself died nine years after her husband from cancer. Creations by RaviliousSome of the creations by Ravilious got lost in the war when a ship with hundreds of works by British war artists for a propaganda exhibition in South-America was sunk. A wall painting which Ravilious had made before the war for Morley College in London got lost when the school building was destroyed by a German bombardment. After the war, Ravilious fell into oblivion, until 1972, when his children retrieved works of their father which had been laying underneath a bed in the house of the artist Edward Bawden, who was friends with their parents. Ever since, Eric Ravilious has become a beloved artist in England whose works have been reproduced in the shape of agenda’s, calendars, postcards, and posters. The documentary Eric Ravilious: Drawn to War gives Eric Ravilious, based on interviews with experts, ego documents and images of his works, the place in English art history he deserves. Whoever wants to see his works in person, can visit the Towner Gallery in Eastbourne and the Fry Art Gallery in Saffron among other places. Ravilious’ wartime works are exhibited by the Imperial War Museum in London. |

| Review: |      (Excellent) (Excellent) |

Information

- Translated by:

- Sebastiaan Berends

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Published on:

- 26-04-2025

Images