Facts Behind the Syria-and-Lebanon Dispute

The War Illustrated, Volume 9, No. 210, Page 150, July 6, 1945.

With the cease fire order to French troops there ended on May 31, 1945, a grave situation in Syria and the Lebanon involving heavy casualties and damage to property., and including the shelling by a French warship of the ancient capital of Damascus. The intricate background of the dispute between France and the Levant Republics is dealt with in this article, specially written for “The War Illustrated” by SYED EDRIS ALI SHAH.

Towards the end of May 1945, while negotiations between France – the mandatory Power – and Syria and the Lebanon were taking place, it was learned that severe disturbances had followed the landing of French reinforcements in the Levant. Conversations ceased immediately, and skirmishes took place between the Arabs and the French and Senegalese forces. Syrian and Lebanese soldiers deserted and their French officers and joined their compatriots fighting in Damascus, Homs, Aleppo, and the Jebel Druse. Damascus, age-old capital of Syria was bombed and shelled by the French forces.

Repercussions were soon felt not only throughout the Arab world but among the Great Powers. Arab solidarity, reinforced by the bonds of the recently created Arab League, which aims at federation of all Arab States, quickly manifested itself in protest. Egypt complained to those countries to which she has accredited diplomats; a strike was proclaimed in Palestine; while the Council of the Arab League was summoned for the first week in June. The Iraq oil pipeline was cut, for the first time since the outbreak of the European war, and the leader of the hundred million Muslims of India registered his protest.

Action to end the bloodshed, it was felt, must be immediate. Good will of the Arab people to the United Nations was at stake; French commercial interests in Egypt were threatened, and the whole world of Islam – numbering over 300,000,000 people – began closely watching the affair as a possible test-case of Western policy towards Islam. There was the further possibility that the many millions professing the Muslim faith in South-East Asia, as well as those in China under Japanese occupation, might fall a prey to enemy propaganda.

Attitude of Our Foreign Office

While fighting continued, and the Levantines called for volunteers for a national army, an official statement was issued from the Foreign Office in London on May 26:

His Majesty's Government are aware of the serious situation which has developed in the last few days in Syria and the Lebanon, but especially in Syria. They regret that the improved atmosphere should have been disturbed by the dispatch of certain reinforcements, and that this should have been the occasion for breaking off negotiations between the Leyant States and the French Government for a general settlement. His Majesty's Government are in constant consultation with the United States Government, and in constant contact with the parties concerned regarding the developments.

The Syrian and Lebanese Ministers in London in a statement said:

If France does not recognize the facts which she has been trying to ignore for the last twenty-five years, namely the desire and determination of Syria and the Lebanon to be completely independent States, and to exercise their legitimate rights as such, this crisis is bound to increase in intensity, and to become less amenable to settlement.

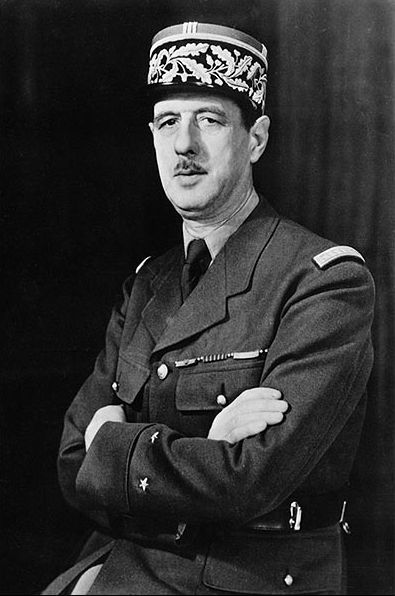

The diplomats were not mistaken. The revolt spread, increasing in violence, until the British Government, with the approval of the Government of the United States, decided to intervene. Mr. Eden read in the House of Commons on May 31 a communication addressed to General de Gaulle, requesting the French forces to cease fire and return to barracks. There was a further suggestion that a conference of the interested parties might be held in London. The cease fire was sounded, and the affair, from being merely an isolated event in France's colonial history, became an international dispute.

To trace the development of the situation it is not necessary to examine closely the evidence as to when the cease fire was ordered, or other minor points that do not in any way affect the fundamental issues; though these have been given a great deal of prominence.

On June 2, 1945, General de Gaulle, at a Press Conference in Paris, asked that the Middle East problem should be viewed as a whole and settlement sought by a conference of all the powers interested: Russia and the U.S. as well as Britain and France, the Arab States as well as their neighbours – on the assumption (maintained by the Arab League) that the Arab world is one unit, politically, economically and historically. Two days later the Council of the Arab League – after condemning the precipitate action of General Oliva Roget, the French commander in Southern Syria, since removed by De Gaulle – announced their agreement with the General that discussion of all Arab questions should be reopened. Thus the affair had vastly outgrown its original proportions.

Mr. Churchill, in the House of Commons on June 5, while willing to discuss these subjects, pointed out that if all the Great Powers were to be invited it might considerably delay the settlement of a matter that should not be left long in abeyance.

The Main Trend of Happenings

Before detailing the points at issue between the Levant Republics and France, it would be advisable to recapitulate briefly the main trend of happenings in the history of French interest in the Levant. In accordance with the Anglo-French Convention of 1919, Great Britain withdrew from the Levant in favour of France. The Mandate was granted to France in 1920 by the Supreme Council of the Allied Powers, and ratified by the League of Nations Council in 1922. This area, with a combined population of something under four millions, is vital strategically, being not so far from Suez in the south, within striking distance of the Middle East oilfields, and communicating with the Persian Gulf to the east. Although these Arab peoples are mixed (including Druses, Alawites, Christians and Muslims) there is no friction or disagreement, particularly on the issue of independence.

After the First Great War the Sykes-Picot agreement had recognized France's “special position” in Syria and the Lebanon. (General Gouraud succeeded Georges Picot as High Commissioner at Beirut in November 1919.) This treaty had provided for an independent Arab kingdom embracing Damascus, Aleppo, Homs and Hama; and the Emir Faissal, son of the King of the Hejaz, ascended the throne in March 1920. In July, the Syrian National Congress unanimously adopted a democratic constitution, by which Syria was declared to be united on a basis of decentralization.

The French High Commissioner, who had been confined to the small area of the Lebanon, issued an ultimatum to Faisal. After a brush with the Arab army, French forces entered Damascus. That same year General Gouraud, French High Commissioner at Beirut, issued a Declaration of the Independence of Lebanon – a marked constitutional advance. Five years later, however, revolt broke out among the Druises when their delegation to he French authorities was imprisoned. At last, in 1936, the French offered the Syrians rights equal to those obtained from Britain by Iraq. But in September 1938 the French refused to ratify their 1936 treaty, in which they had guaranteed independence within three years; trouble in the Levant followed and the High Commissioner declared that no one should have any illusions as to the “permanence of French rule in Syria”. After the French and British announcement of the independence of the Levant in 1941 and 1943, its independence was recognized unconditionally by nine Great Powers and it was able to accredit diplomatic representatives to countries abroad where Levantine interests existed.

The present French demands are for bases in the war against Japan, troops to maintain order, and proposals for negotiations by the Syrians and Lebanese. These are resisted by the Levant Republics on the ground that they are internationally recognized as independent and sovereign; therefore, they say, they are at liberty to behave as such, and to grant no rights if they so desire – particularly for the Japanese war, when there are, they say, better and nearer bases open to the French.

Index

Previous article

Eisenhower: the Man Behind the Name

One year ago this great American led that mighty Allied venture, the seal on which was set with the Unconditional Surrender of Germany. In command of 5,000,000 troops, he has achieved almost overwh

Next article

I Was There! - Today Where Our Invasion of Europe Began

Early in June, Stanley Baron, News Chronicle War Correspondent, flew over the Normandy landing-sites where a year ago Britons and Americans gave new glory to the world. Here he describes the desert