How France's Warships Were Saved From Hitler

The War Illustrated, Volume 3, No. 46, Page 30-33, July 19, 1940.

Following Marshal Petain’s appeal to the Nazis for an armistice, the fate of the French Fleet became a matter of the gravest interest to Britain, now left as the only bulwark of Western civilization. To prevent its falling into enemy hands was imperative, but it was only, alas, by a display of the most resolute British force that this was achieved.

Facing Keitel and his semicircle of grim faced Nazis in the railway coach at Compiegne, Admiral Leluc signed away the French Navy to Germany; True, Article 8 of the Franco-German armistice contained the words "demobilisation" and "disarmament," and also Germany's "solemn declaration" that she would not use the French Fleet during the war or claim it on the Conclusion of peace. But few outside Petain’s Government and perhaps few inside it, save the senile pessimist who was its head, can have put any trust in the written word. Hitler’s vows are made to be broken, and we may be sure that the French ships would not, have been allowed to rot and rust in the French harbours, but in the Fuhrer’s good time work have been added to Mussolini’s fleet and what was left of his own. By such a concentration of naval might Britain’s sea power might well have been challenged with some possibility, even probability, of success.

But Mr. Churchill and his Government and the Admiralty chiefs decided otherwise. Britain’s own salvation demanded the strongest action, and after deliberating a question which Mr. Churchill described as being more grim and sombre than any in his experience, they unitedly took the decision "with aching hearts but with clear vision."

"Early yesterday morning," Mr. Churchill told the House of Commons on July 4th, "after all preparations had been made; we took the greater part of the French Fleet under our control or else called upon them with adequate force to comply with our requirements."

First, those ships were secured which had come into harbour at Portsmouth, Plymouth and Sheerness, two battleships, two light cruisers, some submarines, eight destroyers and some 200 smaller, but none the less extremely useful, mine-sweeping and anti-submarine craft. The operation was carried out without resistance or bloodshed, with the exception of a scuffle on the monster submarine "Surcouf" in which one British officer and an A.B. and one French officer were killed.

Most of Frances naval strength was concentrated in the Mediterranean at Alexandria and Oran. At the former a French fleet, consisting of a battleship, four cruisers, and a number of smaller ships, was lying beside a strong British battle fleet. After negotiations the French admiral, Admiral Godfroy, complied with the British demands.

"Thanks to the friendship formed between the French and British crews, ran an official report issued in Cairo on July 7, demobilization of the French fleet at Alexandria has been carried out without difficulty in a spirit of complete understanding."

There remained the fleet at Oran and its adjacent military port of Mers-el-Kebir on the western side of Algeria. Here were assembled two of the finest of Frances vessels, the "Dunkerque" and "Strasbourg" two other battleships, the "Bretagne" and "Provence" several light cruisers, and a number of destroyers, submarines, and other vessels. On the morning of July 3, Captain Holland, who had arrived in a destroyer, requested an interview with the French commander, Admiral Gensoul, and on being refused presented a document whose vital fourth paragraph began:

It is impossible for us, your comrades up to now, to allow your fine ships to fall into the power of the German or Italian enemy. We are determined to fight on to the end, and if we win, as we think we shall, we shall never forget that France was our Ally, that our interests are the same as hers, and that our common enemy is Germany. Should we conquer we solemnly declare that we shall restore the greatness and territory of France.

Then it proceeded to demand that the French should either:

(a) Sail with us and continue the fight.

(b) Sail with reduced crews under our control to a British port...

(c) Alternatively, if you feel bound to stipulate that your ships shall not be used against Germany or Italy, then sail with us with reduced crews to some French port in the West Indies-Martinique, for instance, where they can be demilitarized to our satisfaction or perhaps entrusted to the United States to remain over until the end of the war, the crews being liberated.

If you refuse these fair offers I must with profound regret require you to sink your ships within six hours.

Failing the above, I have the orders of His Majesty's Government to use whatever force may be necessary to prevent your ships falling into German or Italian hands.

Unfortunately, none of these alternatives proved acceptable. After discussions which continued nearly all day, Admiral Gensoul, acting, no doubt, in accordance with orders dictated from Wiesbaden, where the Franco-German Armistice Commission was in session, announced his intention of fighting.

Some hours earlier a British battle squadron, with cruisers and destroyers, had arrived off Oran under the command of Vice-Admiral Sir James Somerville. Admiral Somerville now received instructions from London to complete his mission before night fell, and at 5.58 he opened fire on the powerful French fleet, which was protected by shore batteries. At 6pm, to quote Winston Churchill, he reported that he was heavily engaged.

"The action lasted some 10 minutes, and was followed by heavy attacks from our naval aircraft carried in the "Ark Royal" At 7.20 Admiral Somerville forwarded a further report which stated that a battle cruiser of the Strasbourg class (later identified as the "Dunkerque") was damaged and ashore, that a battleship of the Bretagne class had been sunk, and another of the same class had been heavily damaged, that two French destroyers and a seaplane carrier, the "Commandant Teste" were also sunk or burned."

While what Churchill, well described as "this melancholy action" was being fought, the "Strasbourg" and some other vessels (later reported to be five cruisers, some torpedo boats, and several smaller vessels) managed to slip out of harbour, and eventually reached Toulon, although the "Strasbourg" was hit by at least one torpedo from a plane of the Fleet Air Arm. None of the British ships engaged in the action was in anyway affected in gun-power or mobility by the heavy fire directed on them, said Churchill, and it was later announced that the casualties were remarkably small, two wounded and two missing.

The French, however, had a very different tale to tell. Quoting what it claimed was a French Admiralty communiqué the German News Agency said that only two survivors were rescued from the "Bretagne" and of the complements of the "Dunkerque" "Provence," and "Mogador" 200 were dead or missing and 150 were wounded, Other French official reports said that more than 1.000 French sailors were killed, wounded, or missing as a result of the battle.

The next day the battle was renewed, and on July 6th units of the Fleet Air Arm raided Oran again and secured six hits on the "Dunkerque" already crippled and driven ashore. So ended the battle of Oran, the first large-scale action since Trafalgar in which British ships had been arrayed against French. Through out the action the Italian Navy, for whose reception, as Churchill said, "We had also made arrangements" and which was considerably stronger than the fleet we used at Oran, kept prudently out of reach.

By now all Frances capital ships were accounted for with the exception of the two largest, the "Richelieu" only just completed, and the "Jean Bart" still under construction.

The "Richelieu" was lying at Dakar in French West Africa, and a British naval force was dispatched to Dakar with orders to present to the French admiral there proposals similar to those offered to his colleague at Oran. As no satisfactory reply was received within the time limit specified, a twofold attack was delivered upon the "Richelieu" in the early hours of June 8th. First a ships boat, under the command of Lt-Commander R H Bristowe, was sent into the harbour and dropped depth charges close under the stern of the warship as she lay at anchor in the shallow water, so as to damage her propellers and steering gear. Then the main attack was, developed by aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm which secured at least five hits with their torpedoes on the battleships mighty frame. Air reconnaissance revealed that the "Richelieu" had a list to port and was down by the stern, while a large quantity of oil fuel covered the water around the ship. As for the "Jean Bart" Mr. Alexander, Britain's First Lord of the Admiralty, told the House of Commons on July 9th that he preferred not to say where she was.

With howls of rage the Germans received the news of these Nelson like strokes. Churchill was assailed with the foulest vituperation, and in French Government circles, too, there was the most bitter denunciation, talk of a stab in the back, "all the more hateful as it was made by our Allies of yesterday." But in Britain and overseas, and in America in particular there was nothing but praise for the resolute way in which a most tragic dilemma had been resolved.

Nevertheless, there was no triumphing in Britain over the issue of the "melancholy action" of Oran. Rather there was the profoundest regret that the stroke should have been made necessary by the treachery of Petain's government.

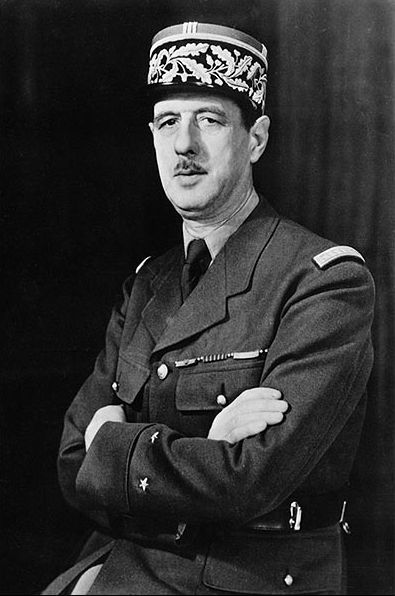

The opinion of Frenchmen in England was well expressed by General de Gaulle when he asked the British people to spare us and spare themselves from any interpretation of this tragedy as a direct naval success. That, he said in a broadcast, would be unfair. The French ships, at Oran were in fact incapable of fighting. They were at their moorings unable to manoeuvre or scatter, with officers and crews who had been corroded for a fortnight by the worst moral sufferings. They gave to the British ships the advantage of the first salvos, which, as everyone knows, are decisive at sea at such a short range. Their destruction is not the result of a fight. Nevertheless, he concluded, I would rather know that the "Dunkerque" our beautiful, our beloved, our powerful "Dunkerque" is aground at Oran than see her one day manned by Germans shelling English ports or Algiers, Casablanca, or Dakar.

Mr. Churchill him-self had no need of apology. "I leave the judgement of our action with confidence to Parliament" he declared in the course of his magnificent oration in the House of Commons on July 4th "I leave it to the nation. I leave it to the United States. I leave it to the world and history."

Index

Previous article

Next article

Anderson Shelters Stand Up To The Test

No better tribute to the efficacy of the Anderson shelter could be desired than that given by these photographs of the erections after German aerial bombs had fallen close beside them. Three are on th