Gerard Hueting, escape help to two airmen in March 1945

Preface

Seventy years ago I came in contact with two crew members of the shot-down American Boeing Fortress (number 43-37913): John Stevens and Stanley Johnston. About a whole lifetime has passed and of course throughout the years memories have been faded and some are completely lost. That is why it is interesting to compare my memories of what happened during the dangerous journey through German-occupied East-Holland with those of John Stevens. Through mediation of Jaap de Boer, a member of the workgroup "Seattle Sleeper", I was able to read John Stevens' report.

What follows is my story of the journey with remarks on where our memories agree, but also where they differ from each other. For me it is remarkable that John never mentioned Stanley Johnston, while I am completely sure we made the journey with the three of us to Winterswijk. Why didn't John mention Stanley at all? What happened after I left the two alone in the barn next to the railway?

The journey

Halfway through March 1945, the war had already entered the fourth year and no signs of reaching the end of all the misery were present. Even though the Allies were able to push the Germans back all the way across the river Rhine, after the failure of "A bridge to far" the situation didn't change much. While the southern part of The Netherlands was liberated, the west was enduring harsh conditions: severe winter and famine. The east faced the same conditions, though not as severe as the western part of The Netherlands. Every day Allied aircrafts flew by, day and night, hundreds of bombers protected by fighter planes or jet fighters with special assignments. Surely there were losses, few cities in The Netherlands were left without seeing a single airplane crash in the area. The crew was often captured right away by the German occupier. However, sometimes one or several crew members managed to escape before the Germans succeeded in capturing them. With local support and aid from the resistance, Allied airmen were given refuge amongst the locals. Many stories have been told about this. I aided a few times close to Zwolle with transporting airmen to different destinations within the city and served as a translator when they needed one.

Now, at the beginning of this story, I had just returned from a short stay in Utrecht and Zeist where I stayed in hiding at Ben and Annie De Haan, in our holiday cottage "de Vechthorst". Our family rented the cottage to Ben, since we couldn't make use of it during the war. Ben was a Royal Netherlands Marechaussee (military police) member. During the war these people where called "the good ones". This meant they were against the German occupation and to be trusted in times of need. Before, I already transported five airmen to Zelhem. We were meant to help them across the Rhine, so they could return to their unit. This is however a whole other story, which is written on this website under the title "Gerard Hueting, what did you do in the war?".

I promised this group of airmen to look out for other possibilities to escape and promised them to return to Zelhem for further aid. Unfortunately I didn't succeed in finding another route. I even tried to swim the river Vecht in order to see how long they could survive in the freezing water. As I found out this wasn't very long, which made swimming across the Rhine in March impossible. I was left with serious bronchitis and high fever. After recovering from my sickness, being ready to leave for Zelhem and to fulfill my promise, I was asked to bring two airmen with me. I don't recall who asked me. Only the fact that Ben de Haan was with me sitting at the table, bending over military maps and planning details of the upcoming journey. Like how the resistance would provide us with bicycles and where to pick up the airmen. I am sure this would happen on the crossing of a dirt road to Nieuw Leusen.

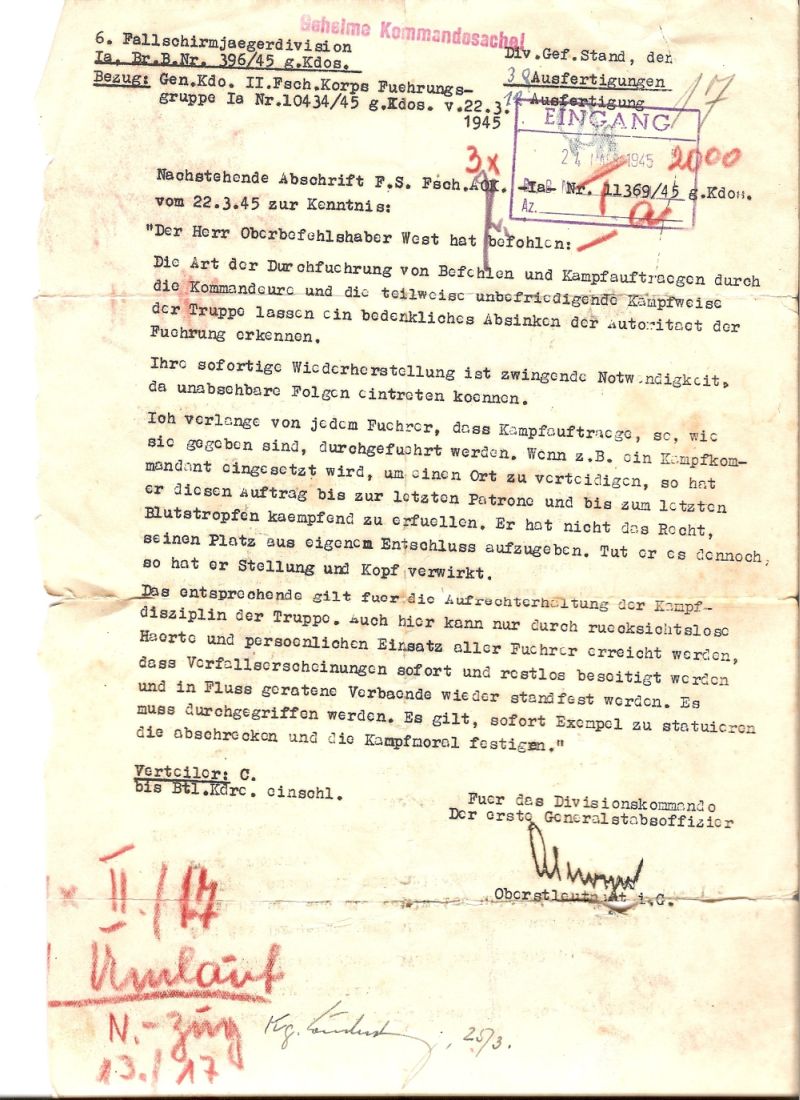

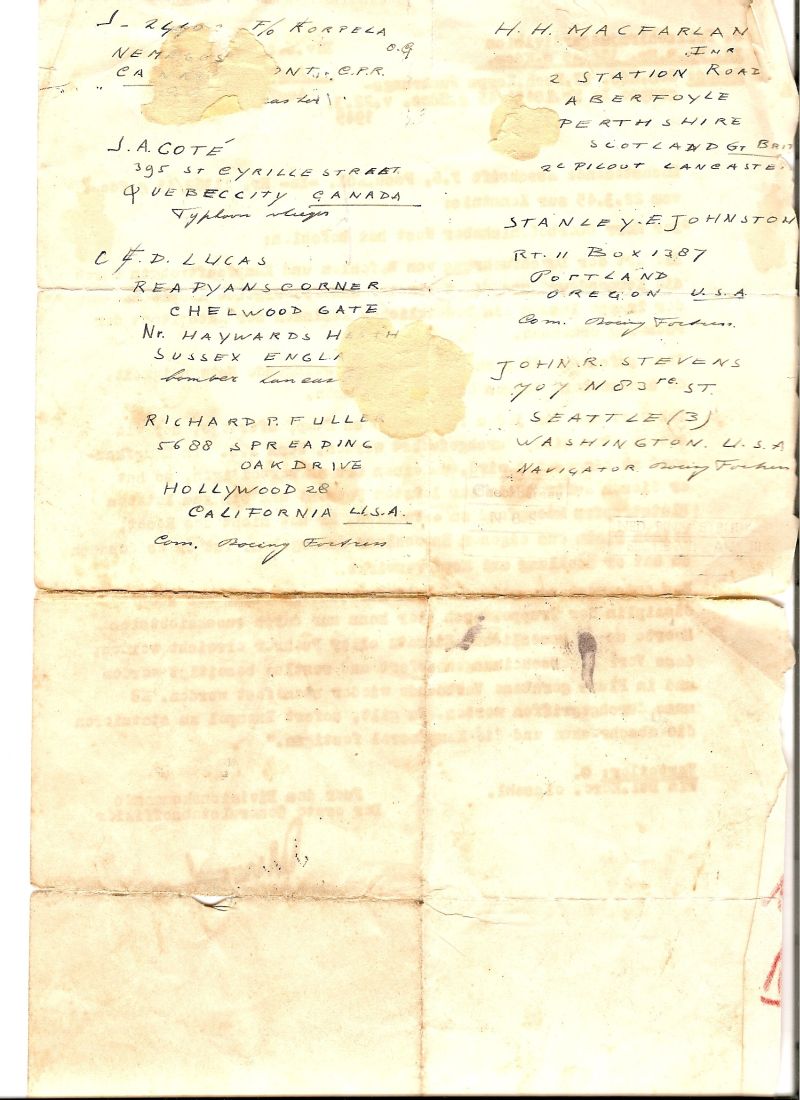

For me it was reasonable to help the two airmen and thus it happened in spring 1945, us three went to the south by bicycle. We aimed for reaching the frontline, and then the liberated area, as close as possible. This matches the story of John Stevens, except for the fact he didn't mention the other pilot. The description of the shelter, a ditch covered in straw, was typical for hiding places during those times. The man who according to John's story was dressed in a NSB uniform, was probably Ben de Haan in his marechaussee uniform. Another shot down airman, Korpela, describes how he made the same mistake. For many years I had forgotten the names of the two travel companions. Only now I remember they were John Stevens and Stanley Johnston. Around 1980 I found, hidden amongst stacks of paper, a document with the names of the seven airmen I had helped long ago. This also included the names of John Stevens and Stanley Johnston.

I can't remember anything of our ride to Zelhem. I remember I prepared the journey well with a special route mapped out so we could avoid as many confrontations with German checkpoints as possible. I used the same army maps I inherited from my father and that I used before as well. The journey was longer than before but also safer by staying away from paved roads, cities and villages. Food and refreshments during our travels? We just knocked on the door of a farm and begged for food like we did before. With one exception all the farmers had been helpful and hospitable. This is remarkable, especially when you think about the danger they underwent and the lack of food they suffered as well. But still their situation was much better than that of all women and elderly who came from the west to Gelderland and Overijssel begging for food in exchange for wedding rings, bedlinen etc.

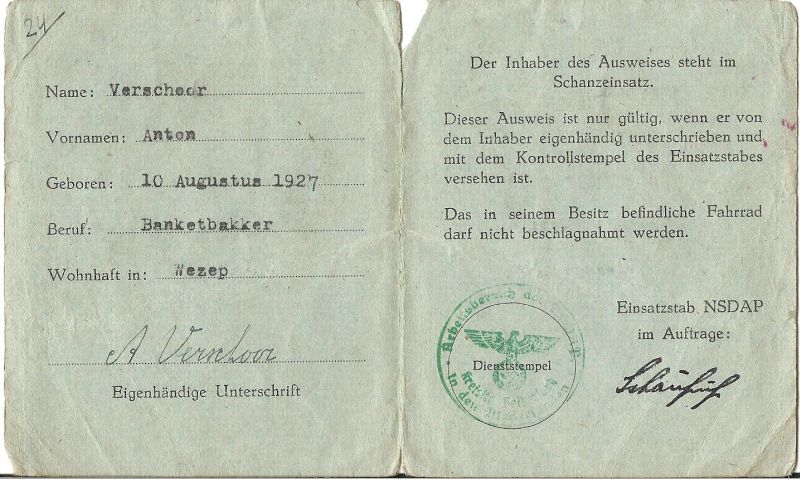

By using my experiences from earlier journeys we were able to make it without difficulties. The possibility of being stopped for a document control was quite high. Men of our age weren't seen much in public. They were in the German labour camps; working on German defenses; or in hiding. That’s why I was riding in front of the two airmen. If I got captured John and Stanley could turn around. John describes how everything was arranged extensively. During our journey there wasn't much time for small talks, so I can't really say anything about my two travel companions.

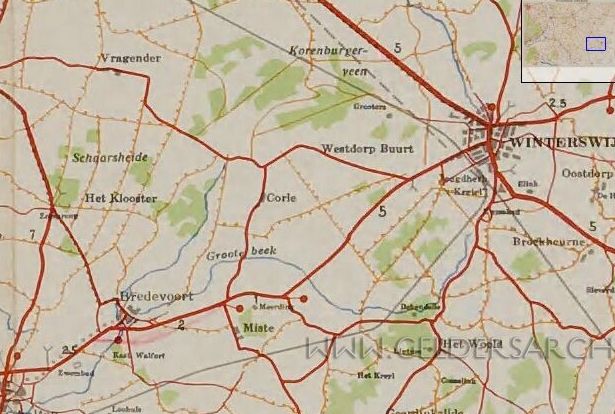

I found my five friends from the former journey in good condition in Zelhem. They had experienced some adventures, like being bombed and having German soldiers quartered in their hiding address. Local contacts didn’t know much about the situation on the frontline. In order to get to know more I went to Aalten the next day to discuss the situation with the local resistance there. Both John and Stanley wanted to get as close to the frontline as possible. So I got the lead to go to Winterswijk and to get a contact address for further help. Back in Zelhem a problem occurred in the evening. I couldn't recall in which farm we resided the night before. At dusk all the farms looked alike. Typically I don’t recall the journey to Zelhem, but this I can clearly recall.

The next morning we were on our way to Winterswijk very early. I can't recall anything of this. Via Aalten we went on a long paved road to Winterswijk. Heather and pine forests. No traffic. Here and there a burned down tank or army truck on the side of the road. German troops were hiding in the forests. Apparently there were strict patrols above the roads by the Allied airforce. The few Germans we met were too busy to stop us. John's memories and mine were similar. Right before Winterswijk we had to pass through a checkpoint. I showed my papers and was accepted, as were John and Stanley. The hiding place turned out to be in the suburbs of the city. No one could really help us here. Eventually I got the address of a farm that would give us shelter.

John wrote that I left him in the forest near Winterswijk. This might be true. But I can't recall where the two airmen were when I was negotiating with the contact person in Winterswijk, nor during the visit of the farm that provided us shelter. It’s logical I left the two men on a temporarily safe place. Someone brought me to the farm. On the farm they were quite afraid of being betrayed. I couldn't blame them for this since the costs were high. Even so, they eventually told us where we could hide on the property. This turned out to be an old barn with an attic, fifty meters away from the railway. The barn was heavily damaged due to earlier bombing raids on the railway. Most of the roof tiles were gone. By a broken ladder we climbed up and found a sleeping bag on a thin layer of hay. It was a long and cold night. The snow reached us through the holes in the roof. Brrr. In my opinion this was around one or two kilometers south-east of Winterswijk.

The next morning I went back to the farm where I, in a pleasantly warm kitchen, asked for food and drinks for the two men I had left in the barn. In exchange for rationing coupons and money I got a piece of bread and water. All this while the family was enjoying a high pile of deliciously smelling pancakes. This is the first and only time in all my journeys I was treated like this. Back in the barn we talked about "what's next?". We concluded we had only two options: John and Stanley would stay here to wait out the arrival of the Allies, which could be in any moment, or they would try to get across the frontline. Because the local underground forces had promised to look after them and the farmer, it didn't make any sense for me to stay any longer. After all I had promised to help the pilots in Zelhem as well. They decided eventually to stay and wait.

This deviates from what John described. He said I left him on the same day of arrival in Winterswijk. I am completely sure I spent the night in the barn. It was too late for me to return to Zelhem before Spertijd [the curfew] would start. I also clearly remember the long discussion in the morning with John and Stanley about what to do next.

There is not much to say more. I cycled back to Zelhem. The way back was long and exhausting. While I was at a checkpoint I was shot at by seven Tempest fighter planes and had to take cover in a ditch. Near Aalten I saw a group of people on the road; I didn't trust the situation and even though I was tired, I took a detour. Fortunately. Later I heard that they were taken as hostages. Maybe as retaliation for the attack on Hanns Rauter? Some days later the first Canadian troops liberated the eastern part of The Netherlands. I have never heard anything from John or Stanley again and I assumed that they made it safe through the war.

I don’t know how the names of John and Stanley arrived on the previously mentioned lost paper. Probably they were copied later on this document that I carried with me when I was working as a translator for a Canadian armored car. I helped them with interrogations and research on captured documents. I recall saying goodbye to the five airmen in Zelhem and writing down their names on the paper as well.

Earlier in my description I said that I didn’t have a chance to get to know John and Stanley and that I couldn’t tell much about them. But one thing is solid in my memory. The quality of both characters, the courage to take this journey, the will and sense of duty that kept John and Stanley fighting to return to their unit to keep on fighting the Nazis; this in particular. But why John didn't mention Stanley at all during this dangerous journey is a mystery for me until this day.

Gerard Hueting, New-Zealand 2014

| Note by the workgroup "Seattle Sleeper" in Hualerwijk, Netherlands

Through the attention of Teunis Schuurman (PATS) the workgroup acquired the name of Mr. Hueting. We were talking about the lists of pilot helpers with Mr. Schuurman which can be found on the website of Bruce Bolinger. On there are over 7500 Dutch names written of people who claimed to have helped a pilot. wwii-netherlands-escape-lines.com see "Helpers of Allied airmen". A digital access version can be found on haulerwijk.com/~seattlesleeper/Nara-Gov.htm. When the talk came to an end, we noted that it was a shame that the person in Stevens story did not have a name. This turned out to be a Bingo-remark. To our surprise, and with aid by Go2War2.nl (now TracesOfWar.com), within 12 hours the first contact was established. The writing of John Stevens has been dated July 1945. Our group as well has no clue why Johnson wasn't mentioned in his story. In the first part he was mentioned however. Possibly this report has been made on the basis of MIS-X reports that all crew members had to do, after a crash, after returning back to base. Hopefully the lost parts can be resolved by the documents that have been requested from the National Archives at College Park, Maryland. We hope to come up with a more elaborate story by the end of this year (2014). Contact information of the workgroup "Seattle Sleeper" is known by the editorial staff of TracesOfWar.com. See also: www.haulerwijk.com/~seattlesleeper |

Definitielijst

- mine

- An object filled with explosives, equipped with detonator which is activated by either remote control or by colliding with the targeted object. Mines are intended to destroy of damage vehicles, aircrafts or vessels, or to injure, kill or otherwise putting staff out of action. It is also possible to deny enemy access of a specific area by laying mines.

- NSB

- National Socialist Movement. Dutch political party sympathising with the Nazis.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Information

- Translated by:

- Joshua Rijsdam

- Published on:

- 08-06-2019

- Last edit on:

- 21-11-2023

- Feedback?

- Send it!