Preface

When the Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini was convinced that his German ally would win the Blitzkrieg against the Low Countries and France, he openly supported Adolf Hitler by declaring war on France and Great Britain on June 10, 1940. That day, he invaded southern France with a small force to conquer the Alps near the Franco-Italian border and the border regions near Nice. However, Mussolini also had set his sights on the French colonies in North Africa. On June 22, 1940, France signed an armistice with the representatives of the Third Reich. Three days later, France concluded a similar armistice with the Italians.

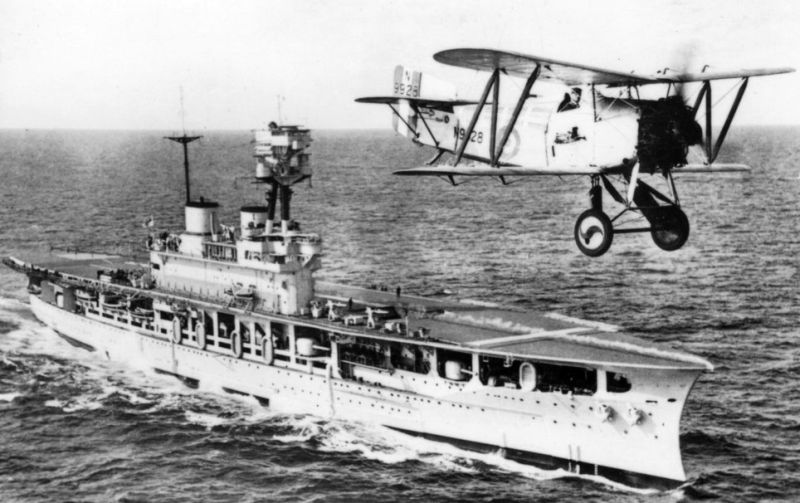

The R.A.F. attacked the Italian battleships in Taranto with obsolete Fairey Swordfish biplanes. Source: Wikipedia

The French armistice with Hitler and Mussolini was a major setback for the British. Great Britain not only lost her ally France, but she got two more opponents. Not only Italy, but also Vichy-France, a region in unoccupied France, which collaborated with Nazi Germany under the authoritarian leadership of Marshal Philippe Pétain. One of the conditions in the armistice with Germany was that the French Fleet would be confined to their home ports, as was usual practice in peacetime. The British also considered the French surrender a unilateral breach of their agreement with France, concluded on March 26, 1940, to not individually agree on a ceasefire with Germany. Hence after June 22 Winston Churchill perceived the French Fleet as a potential threat. During Operation Catapult, the Royal Navy would even attack French Navy ships in colonial ports.

Churchill felt increasing pressure from the Axis Powers especially in the Mediterranean. The British needed free sea passage in this area to keep the supply lines open from Gibraltar to Egypt, which they controlled. As Great Britain was an island nation and a colonial power, Egypt was essential for her due to the presence of the Suez canal. From 1869 onwards, this waterway connected the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea and therefore offered a direct route between the Atlantic and the Indian Oceans. The Royal Navy also needed to maintain supremacy over the Italians in the Mediterranean because of her ally, Greece, which had been attacked by the Italians in October 1940 and later on by the Germans. For the Italians too, there was a need for free passage across the Mediterranean Sea for the vital supply routes to their colony of Libya.

By June 1940, the Italian Royal Navy, the Regia Marina, was the fourth largest in the world. Only the Royal Navy, the US Navy and the Japanese Imperial Navy were larger. Benito Mussolini had 6 battleships, 19 cruisers, 59 destroyers, 67 torpedo boats and 116 submarines at his disposal. Most of these ships were somewhat outdated and the crews were not (yet) in utmost state of readiness, but in terms of numbers, the Italian Royal Navy was a force to be reckoned with. After three minor inconclusive battles between the Royal Navy and the Regia Marina, the British decided to deliver a substantial blow to the Italian fleet. Because Mussolini feared a direct confrontation with the Royal Navy, he kept his warships safely in port at Taranto, in the heel of the Italian boot. This way his fleet posed a continuous and serious threat to the British while avoiding a sea battle, a so-called Fleet in Being.

Definitielijst

- Blitzkrieg

- The meaning of this word is “Lightning War”. Short and fast campaign. As opposed to a trench war the Blitzkrieg is very quick and agile. Air force and ground forces work closely together. First used against the Germans (September 1939 in Poland.

- Fleet in Being

- A war fleet preventing battle but by its presence and force forcing the enemy to take measures by allocating forces to keep an eye on them thus preventing those forces from being deployed elsewhere.

- Marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Preparations for the attack

If the Italians are not coming to us, we will go to them, the British thought, and they deployed an attack plan from 1935. At the time, Italy had started a war against Ethiopia and the British, who had major interests in East Africa, launched a surprise attack with torpedo bombers on the Italian naval base at Taranto. The plan was very risky and the incumbent Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, Admiral Dudley Pound, was concerned about survival of the aircraft carriers and the torpedo bombers during the mission. In 1938, during the negotiations of the Munich Agreement, in which France and Great Britain, under pressure from Hitler and Mussolini, agreed to the aggressive annexation of the Czech Sudetenland to prevent a war, the plan was taken up again. This time by the captain of the aircraft carrier H.M.S. Glorious, located in the Mediterranean, Arthur Lumley St. George Lyster.

Admiral Andrew B. Cunningham, who had succeeded Pound on June 6, 1939, initially did not like an air raid on the Italian base. Like so many conservative British officers, he considered aircraft carriers and naval aviation as second-class compared to battleships and cruisers. The aircraft aboard the British aircraft carriers, which belonged to the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm, in particular Fairey Albacore, Fairey Fulmar, Curtiss Cleveland and Fairey Swordfish, did not make much impression on the naval officers.

The latter aircraft in particular were not popular within the Royal Navy. The slow biplanes were in fact already obsolete when they were developed and delivered to the navy in the early 1930s. Yet it was these decrepit Swordfish aircraft that could drop both torpedoes and bombs and could take off and land on the narrow flight deck of a pitching and rolling carrier. The small but robust biplanes were even nicknamed "Stringbags" (shopping bags), due to the endless variety of equipment that they could carry. Moreover, the primitive biplanes could be hit by bullets multiple times without serious damage. The fuselage consisted of a thin tubular airframe covered in fabric, so that bullets or grenades would pass straight through it instead of exploding like they would on a metal fuselage.

To attack the Italian warships in Taranto, the British naval officers had to opt for an air raid. And that, despite skepticism, could only be undertaken by the Fairey Swordfish. Admiral Cunningham had his staff examine the plan, together with Vice Admiral Lyster, commander of the Fleet Air Arm who was on board the Illustrious. The new aircraft carrier H.M.S. Illustrious had just arrived in Egypt and enough biplanes could take off to venture the attack from that ship and the old carrier H.M.S. Eagle. The British ships would be very vulnerable if the Italian navy was to counterattack, hence the decision to attack at night. This would also increase the chances of success for the slow torpedo bombers. The attack was originally scheduled for October 21 under the code name Operation Judgment. The British assault fleet would first sail from Alexandria in Egypt to Malta so the Italians would not smell any trouble.

The mission was plagued by bad luck from the start. Even before the fleet left Egypt, the Illustrious lost a few Swordfish aircraft when engineers fitted an auxiliary fuel [tank] for the more than 186 mile long flight. A [tank] caught fire due to sparks and one of the planes exploded in the resulting sea of fire, which quickly spread. Two Swordfish aircraft were lost and five were damaged. The attack was then postponed until October 31. On that date, however, the pilots were unable to take advantage of full moonlight, as a result of which the attack was postponed again until November 11. After the battle fleet set sail on November 6, the old aircraft carrier H.M.S. Eagle had to return to Alexandria due to technical problems. Six Swordfish aircraft were transferred to the Illustrious, but the air fleet had been reduced to a maximum of 24 aircraft.

H.M.S. Illustrious continued and was escorted by the heavy cruisers H.M.S. York and H.M.S. Berwick, the light cruisers H.M.S. Gloucester and H.M.S. Glasgow and the destroyers H.M.S. Hasty, H.M.S. Havock (H43), H.M.S. Ilex (D61) and H.M.S. Hyperion (H97). The attacking Swordfish came from 813, 815, 819 and 824 Naval Air Squadrons. They would attack in two waves. The first wave of attack would be led by Lieutenant Commander M.W. Williamson and the second by Lieutenant Commander J.W. Hale. In the air, the torpedo bombers were protected by fourteen Fairey Fulmar and four Sea Gladiator fighters from 806 squadron until just before the strike.

After two reconnaissance flights from Malta over Taranto, pilot Adrian Warburton reported, from his Martin Maryland of RAF No. 431 General Reconnaissance Flight, that six battleships, seven heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, eight destroyers, five torpedo boats and sixteen submarines were berthed in the two ports of Taranto. They consisted of a large outer harbor, the Mar Grande, and a smaller inner harbor, the Mar Piccolo. In the main harbor, which was under the supervision of Harbor Commander Vice Admiral Arturo Riccardi, there were also minesweepers, a mother ship for float planes and smaller auxiliary vessels. On the banks there were a large oil depot, workshops, anti-aircraft batteries, searchlights and 90 bases for barrage balloons. Due to a shortage of gas for the balloons in November 1940 only 27 barrage balloons were serviceable. The Italians did not yet possess radar equipment, but they installed thirteen listening posts which were manned round the clock.

The six battleships would be the most important targets for the Royal Navy. The Regia Marina had two Conte di Cavour class battleships, the Conte di Cavour and the Giulio Cesare, which had been launched in 1911 and modernized in 1933. In addition, the two Caio Duilio class battleships, the Caio Duilio and the Andrea Doria, were based in Taranto as well. These battleships had been launched in 1913, but also thoroughly modernized in the 1930s. The showpieces of the Regia Marina were the two brand new battleships of the Vittorio Veneto class. The Vittorio Veneto and the Littorio were completed in 1940 and were both anchored in Taranto. The sister ships Roma and Impero were still under construction in La Spezia and Trieste respectively. The 734,91 feet long battleships had a displacement of over 41,000 tons and nine 38 cm, twelve 15 cm and four 12 cm guns.

Definitielijst

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- RAF

- Royal Air Force. British air force

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

The air raid

In the evening of November 11, 1940, the British sent a Short Sunderland flying boat from Malta to Taranto to make sure the Italian warships had not sortied. The reconnaissance flight alerted the Italian forces, who suspected an attack was imminent. However, since they were without any radar, they could do little else but wait for whatever came along. The British assault fleet then met at the Greek island of Kefalonia, about 170 miles from Taranto. The first attack of twelve Fairey Swordfish aircraft took off from H.M.S. Illustrious around 9:00 p.m., followed by a second wave of nine more than an hour later. About a third of the biplanes were equipped with five 60-pound bombs and the rest with torpedoes. The planes that took off first also had parachute flares on board that would illuminate the Italian port.

Loading a torpedo on a Fairey Swordfish aboard a British aircraft carrier. Source: Armoured Carriers

Admiral Cunningham and Vice Admiral Lyster feared that no more than half of the Swordfish aircraft would return. This would mean that ten or eleven of the 21 pilots and 21 observers/gunners would survive. The survival rate of the attackers in the second wave was even lower since the element of surprise had been lost. Because the leading aircraft of the first attack wave was too far ahead, it arrived fifteen minutes earlier above the Italian port than planned.

Immediately the Italians alerted the anti-aircraft batteries which promptly took action. As a result, the element of surprise of the first wave of attack had virtually disappeared.

The pilots of the Swordfish aircraft, however, had no choice but to continue their mission. The air offensive was launched at around 11 p.m. by the two planes that dropped the flares and then their bombs. This made the silhouettes of the Italian ships clearly visible for the tailing aircraft in the dark night. Moreover, the bombing caused confusion and panic among the Italian defenders. The Swordfish flew through a rain of bullets. Pilot Richard Janvrin remembered: "We just had to get through it and it didn't do much to us. You didn't think you could be hit by it."

The flight leader of the first attack wave, Lieutenant Commander Williamson, dropped his 1,600 pound torpedo before turning away sharply. Williamson flew so low when dropping the torpedo that the wing tip of his Swordfish hit the water surface during the turn. "I fell out of the plane. We were six feet above the water, so it wasn't a long fall. The anti-aircraft fire from the shore batteries was so heavy and the water was swirling," Williamson's observer Norman Scarlett later recalled. Pilot Williamson emerged next to him and together they kept afloat by clinging to the remains of their aircraft. They did not know yet that they had struck the Conte di Cavour with a torpedo and that the battleship was sinking. For the time being, they brought themselves to safety by swimming to a floating dock and went into hiding.

Meanwhile, the torpedoes of two Swordfish from the first strike wave missed their targets, but a third blasted a hole below the water line in the hull of the Littorio. The last aircraft of the wave was flown by Lieutenant M.R. Maund. He approached the port by flying low over the city of Taranto in the direction of the inner port. "I went full speed and headed for the entrance to Mar Piccolo. But suddenly it was like all hell broke out!", he said after the war. The Italian anti-aircraft guns had great difficulty with the low-flying aircraft because the gunners were afraid to hit their own ships. "The sea was so close to our landing gear that I was wondering what would happen first: fire the torpedo or hit the water. Then we pulled up and pressed the release button almost instantly. A vibration told us that the fish was in the water," said Maund. He aimed at the battleship Vittorio Veneto, but the torpedo hit the bottom and exploded prematurely.

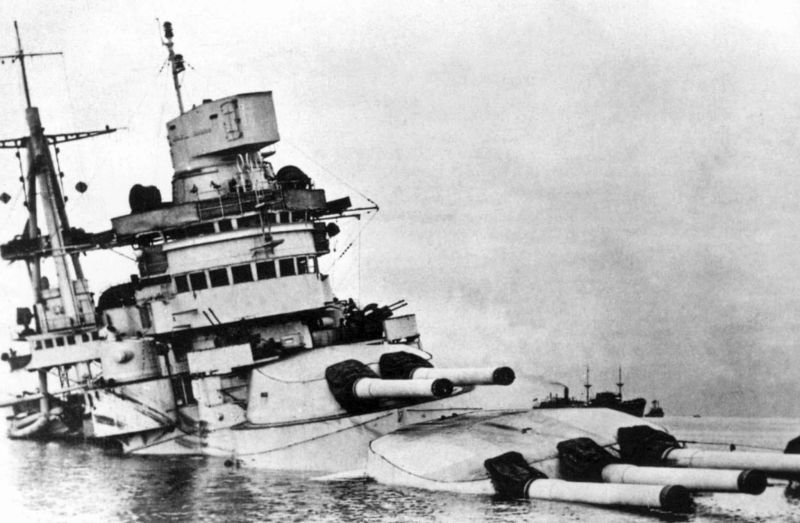

The attack of the first wave lasted about forty minutes. The twelve British aircraft hit two battleships with torpedoes and only lost a few Swordfish. To the second wave of attack, the port of Taranto was a frightening spectacle. A few described the port as an anti-aircraft volcano. This attack was also preceded by the dropping of two flares after which the biplanes spread over the harbor. A first torpedo hit the Littorio again and a second blasted a third hole in the battleship's hull.

The crew of the Swordfish who attacked the heavy cruiser Gorizia was less lucky. Just before the strike, the aircraft was shot down by anti-aircraft fire and crashed into the water. Moments later, a British torpedo hit the battleship Caio Duilio. The Vittorio Veneto escaped a hit for the second time when a torpedo struck a sandbank just a few hundred yards from the ship. The Swordfish was riddled with anti-aircraft bullets, but miraculously it remained in the air. The last British plane bombed the heavy cruiser Trento, but the bomb went straight through the deck of the Italian ship without exploding. The British air raid on Taranto was over.

An hour and a half after the attack, the first Swordfish returned aboard the Illustrious. To the big surprise of the aircraft crew, Admiral Cunningham and Vice Admiral Lyster, one after another, more or less battered Swordfish aircraft returned. Only two planes were lost. Williamson and Scarlett were taken prisoner by the Italians and the two crew members of the biplanes hit by anti-aircraft guns did not survive.

The Italians suffered more significant damage. The battleships Littorio, Caio Duilio and Conte di Cavour were hit by one or more torpedoes. The Conte di Cavour sunk in the shallow waters of the Mar Grande and never returned to full service again. The repair of the Littorio would take four months and that of the Caio Duilio six. In addition, three cruisers and two destroyers were damaged, as well as the Italian seaplane base, and the oil depot was on fire.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- radar

- English abbreviation meaning: Radio Detection And Ranging. System to detect the presence, distance, speed and direction of an object, such as ships and airplanes, using electromagnetic waves.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

The aftermath

The successful British air raid on Taranto had several immediate and indirect consequences. The first and most important immediate consequence was the dominance of the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean Sea from the night of November 11 and 12, 1940 onwards.

With the attack on Taranto, 21 obsolete torpedo bombers put half of the Italian battleships out of action for months. Winston Churchill said, "This battle has changed the power balance in the Mediterranean." Admiral Cunningham wrote: "I don't think their remaining three battleships will face us and if they do, I'm quite prepared to take them on with only two of my own." The Italians already withdrew their fleet on November 12 to the much safer port of Naples, far away from the British convoy routes. There was no longer any question of a Fleet in Being. During the later naval battles between the British navy and the Regia Marina, the former always appeared more superior. This was not because the Royal Navy had more ships than the Italian navy, but the British were more aggressive and not afraid to suffer losses. The Italians, on the other hand, were very careful, partly due to the defeat in their home port.

The British air raid on Taranto marked a turning point in military maritime history. Until November 1940, the battleships had always been the primary weapon of all major naval powers. It suddenly turned out that the powerful battleships stood no chance in a coordinated air attack. Admiral Cunningham, who was previously very skeptical of deploying naval aviation in naval operations, now said: "Taranto, and the night of November 11 and 12, 1940 should be remembered for ever as having shown once and for all that the Navy has its most devastating weapon in the Fleet Air Arm. " The Royal Navy itself would also be confronted with the fact that battleships, however modern, did not stand a chance in an air strike. On December 10, 1941, the British battle cruiser H.M.S. Repulse and the battleship H.M.S. Prince of Wales were sunk by Japanese planes near Singapore. The Repulse was old, but the Prince of Wales was commissioned as early as January 19, 1941. Even the most powerful Japanese battleships, the largest and strongest ever built, the Yamato and the Musashi, were defeated by aircraft in the battle between the US Navy and the Japanese Imperial Navy in the Pacific.

Perhaps the most important consequence of the Taranto raid was the fact that it inspired the Japanese to do the same with the American naval base in Hawaii, Pearl Harbor. While the British celebrated their success, representatives of the Japanese navy visited Italy. Shortly after the attack, Takeshi Naito, the Japanese assistant naval attaché to Berlin, flew to Taranto to investigate its defense and damage. Later, several Japanese admirals visited Taranto, where they had lengthy conversations with the staff of the Regia Marina. It is not known whether they actually emulated the attack on Pearl Harbor in the early morning of December 7, 1941, based on this information, but both air raids were similar. However, the Japanese attack was a considerably larger operation. From six Imperial Japanese fleet carriers, 350 bombers and torpedo aircraft were launched that would cause major damage to the battleships docked in the port and to the naval base itself.

Definitielijst

- battleship

- Heavily armoured warship with very heavy artillery.

- cruiser

- A fast warship with 8,000 – 15,000 ton displacement, capable to perform multiple tasks such as reconnaissance, anti-aircraft defence and convoy protection.

- Fleet in Being

- A war fleet preventing battle but by its presence and force forcing the enemy to take measures by allocating forces to keep an eye on them thus preventing those forces from being deployed elsewhere.

- raid

- Fast military raid in enemy territory

- torpedo

- A weapon of war. A cigar shaped body fitted with explosives and a propulsion and control mechanism. Intended to target after launch a nearby enemy ship and disable it by underwater explosion.

Information

- Article by:

- Peter Kimenai

- Translated by:

- Kimberley Tang

- Published on:

- 15-03-2020

- Last edit on:

- 30-09-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!