Youth and civil service career

Friedrich Wilhelm Kritzinger was born April 24, 1890 in the little village of Grünfier, the son of a Lutheranian reverend. At the time Grünfier was located in the Prussian province of Posen (in Polish: Poznań), which would be ceded to Poland after the First World War. After 3 years of private education, young Kritzinger attended grammar school in Posen from 1899 to 1904 and subsequently the grammar school in nearby Gnesen (in Polish: Gniezno) until 1908. After graduation he studied law at the universities of Freiburg, Berlin and Greifswald (on the Baltic coast in the northeast of the present Federal Republic). On October 11, 1911 he passed his first state exam Referendarexamen in order to be admitted to public service. Between 1911 and 1913 and between 1920 and 1921, he served as an apprentice on the courts of Mogilno (now in central Poland) and Berlin and at the Staatsanwaltschaft in Hirschberg (today Jelena Góra in the southwest of Poland).

Kritzinger’s budding civil service career was interrupted by the First World War. Between 1914 and 1918 he served in a Prussian infantry battalion, Jäger-Battalion Von Neumann (1. Schlesisches) Nr. 5, and reached the rank of reserve lieutenant. He was slightly injured at least once. In the last phase of the war, he was reported missing but actually he had been made a prisoner-of-war by the French. He returned to Germany in 1920.

He resumed his civil service career and in May 1921, he passed his second state exam, Assessorexamen. Between July and September of that year he was assistant judge at the court of Striegau in Lower-Silesia (today Strzegom in the southwest of Poland) for a while. He would remain a devoted member of the Protestant Church all his life and on May 30, 1923, he married Walti Luise Agnes, Duchess of Schwerin und Krosigk, (1897-1996), the daughter of a large landowner. The couple had three children.

Following his job as assistant judge, until 1925 he was employed as scientific associate at the Reichsjustizministerium where he was involved in questions of international law. After a short term at the Prussian Handelsministerium - in his capacity as Landesgerichtsrat, he was active in the field of savings banks and monetary policy - he returned to the Reichsjustizministerium in 1926. Initially he resumed his work in the field of international law and from 1928 onwards, he specialized in constitutional questions. He made a quick career and in 1930 he was appointed Ministerialrat, a high function in civil service. As such he frequently attended sessions of the Reichsministerrat as advisor.

During this period of the Weimar Republic, civil servant Kritzinger wasn't active politically. He claimed that at the Reichstag elections he voted for the Deutschnationale Volkspartei, DNVP until 1933. This was a national-conservative party with monarchist and anti-Semitic elements in its program.

It wasn't exceptional for Kritzinger to vote for a party that didn't shun anti-Semitism. Within the German officers corps and among high ranking civil servants, a mood of so-called cultural anti-Semitism prevailed. This version of anti-Semitism was spread widely among the conservative elite of the empire and the Weimar Republic. It focused mainly on the Jews from Eastern-Europe and should not be mistaken for the racial and radical anti-Semitism of the extreme right which in the end led to large scale persecution and mass murder by the Nazis. Female Israeli historian Shulamith Volkov describes this conservative version of the German anti-Semitism as some sort of cultural code which caused the elite to condone the radical, racial anti-Semitism of the Nazis. As a result, there was hardly any opposition from German high ranking officers and civil servants against the persecution of Jews in Nazi-Germany so Kritzinger was no exception.

Definitielijst

- First World War

- Took place from 1914 till 1918 and is also named The Great War. The conflict started because of increased nationalism, militarism and neo-colonialism in Europe. Two alliances battled one another during the 4-year war, which after a dynamic start, resulted into static trench warfare. The belligerents were the Triple Alliance (consisting of Great-Britain, France, and Russia; later enlarged by Italy and the USA, amongst others) on the one hand and the Central Powers (consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman empire) on the other hand. The war was characterized by the huge number of casualties and the use of many new weapons (flamethrowers, aircraft, poison gas, tanks). The war ended in 1918 when Germany and its allies surrendered unconditionally.

- infantry

- Foot soldiers of a given army.

- Jäger

- Also called fighter plane. Fighter planes can be used for air defence (armed with guns and/or carrying guided missiles) or for tactical purposes (armed with nuclear or conventional bombs or rockets). The aircraft used for tactical purposes are also called fighter- bombers because they are bombers with the speed and manoeuvrability of a fighter. Tactical fighters, equipped with photographic equipment are also used as reconnaissance plane.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- Weimar Republic

- Name for the German republic from 1919 until 1933. Hitler ended the Weimar republic and founded the Third Reich.

Top notch Nazi official

Following the Nazi seizure of power on January 30, 1933, Kritzinger remained a hardly noticeable high ranking official at the Reichsjustizministerium. He conformed with the new rulers and in his capacity of specialist in state law, he contributed to laws aimed at converting Germany into a dictature. He played a role for instance in the legal foundation of the disbanding of the free trade unions. The assets of the unions were confiscated, the right to strike was abolished and the leaders disappeared behind bars. As early as May 10, 1933, the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (DAF was founded, a uniform organization of employers and employees the free trade unions were compelled to join.

Early 1938, Kritzinger moved up further towards the center of power in Nazi-Germany. Hans Heinrich Lammers, chief of the Reichskanzlei needed an expert in state law and asked Kitzinger to switch to his department. Kritzinger wasn't overly enthusiastic. Lammers had to repeat his request several times and Reichsjustizminister Franz Grüntner drew Kritzinger’ s attention to his ‘duty’ to accept this request. In February 1938, Kritzinger gave in to the pressure and went to work in the Reichskanzlei as second man to Lammers.

Hans Lammers, chief of the Reichskanzlei, in the uniform of an SS-Brigadeführer. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-C16771 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

The Reichskanzlei was Adolf Hitler’s office in his capacity of Reichskanzler and was in particular responsible for Hitler’s contacts with the other administrative organs of the Reich such as all the ministries. It was located on Voßstraße in Berlin. In his capacity of Ministerialdirektor Kritzinger became the head of Abteilung B including the departments of justice, finance and economy. In 1938, he became a member of the NSDAP (number 4,841,517) and rose in the pecking order: early 1942, Adolf Hitler promoted him to Undersecretary of State and on November 21 of that year to Secretary of State at the Reichskanzlei. His main tasks included making the cooperation between the various ministries as smoothly and efficiently as possible when drafting legislation. As Lammers had been added to Hitler’s staff during the war, he was frequently present in Hitler’s train or one of his field headquarters so in practice, Kritzinger supervised the daily work at the Reichskanzlei.

The Reichskanzlei on Voßstraße, Berlin Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1988-092-32 / Obigt, W. / CC-BY-SA 3.0

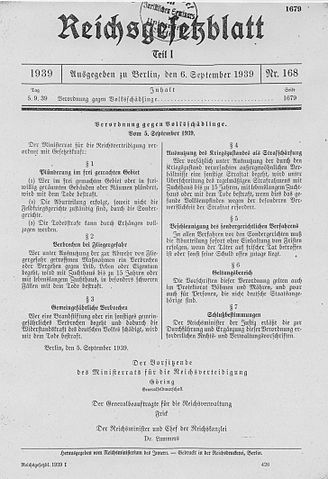

Apart from his other tasks, Kritzinger did cooperate in drafting draconic legislation. Under his responsibility, the Verordnung gegen Volksschädlinge (Regulation against individuals harmful to the population) of September 5, 1939 was worked out. With this, Nazi jurisdiction was given an instrument to impose the death sentence for a series of vaguely described punishable facts like plunder and arson. This regulation, issued four days after the start of World War Two was meant, together with the Kriegssonderstrafrecht (special military criminal law) to protect the so-called ‘domestic front’ against ‘unscrupulous harmful elements’ who had to be eliminated mercilessly (ausrotten) from social life.

Kritzinger’s authority also encompassed work in the field of the Jewish problems, in particular to rob the German-Jewish population of its rights. For instance, the Elfte Verordnung zum Reichsbürgergesetz (11th regulation of the citizens law) of November 25, 1941 for which he was responsible, was notorious. This law was one of the Nuremberger Laws of 1935 and the 11th Regulation stipulated further rules.

This regulation stipulated that all German Jews who had emigrated - between 250,000 to 280,000 persons - lost their German nationality retrospectively. German Jews who had emigrated after the introduction of the 11th Regulation also lost their German citizenship. As German Jews had been prohibited to emigrate, pursuant to an order by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler of October 18, 1941, deportation to the occupied areas outside the German Empire was equated to emigration. There was a problem however: the final destination of most of the deportation trains was the General Government, the Reichskommissariat Ostland and the Reichskommissariat Ukraine. Since the occupation, these areas belonged to the Third Reich. This was solved by Reichsinnenminister Wilhelm Frick; on December 3, 1941 he ruled in a memorandum that these areas were categorized as ‘foreign countries’ along the lines of the 11th Regulation.

Within the framework of the Entjudung (getting rid of Jews) this regulation mentioned before also provided the means of confiscating the assets of German Jews on behalf of the German Empire in case of deportation. At the loss of German citizenship, these ‘assets hostile to the population and state’ (Volks- und Staatsfeindliches Vermögen) would be ceded to the state automatically. Afterwards the money was to be used in whatever way for the solution of the Jewish problem. Hence, the Jews were to finance their own downfall. If debts were part of the assets, those were not taken over by the state and not paid to the debtor out of the assets. Inheriting and granting of Jewish assets was prohibited as well.

Definitielijst

- Abteilung

- Usually part of a Regiment and consisting of several companies. The smallest unit that could operate independently and maintain itself. In theory an Abteilung comprised 500-1,000 men.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

Participation in the Wannsee Conference

On January 20, 1942 a conference was held in a villa in Berlin, 56-58 Am Großen Wannsee aimed at organizing and coordinating the Endlösung der Judenfrage (final solution of the Jewish question). The decision to mass murder the Jews in Europe was not taken here though - that decision had already been taken by the Einsatzgruppen in the areas occupied by Nazi-Germany following the invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. The point on the agenda was the organization and coordination of the deportation and extermination of the entire Jewish population in Europe. German historian Peter Longerich aptly characterized the conference in railway terms as ‘setting switches correctly’: the when, how and where of the Endlösung was streamlined between the various government and party organs involved.

The meeting was called by SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich in his capacity as chief of the Sicherheitspolizei, SIPO and the Sicherheitsdienst. Chaired by Heydrich, 14 high ranking officials of the NSDAP, the SS and officials of various ministries attended the conference.

One of those officials was Ministerialdirektor Friedrich Kritzinger, the eldest of those present. He traveled to the villa on Wannsee together with his colleague and close friend in the Parteikanzlei of the NSDAP. Dr Gerhard Klopfer. Kritzinger was the representative of this bureau which was to play an important coordinating role in the cooperation between the various agencies involved in the final solution. He was invited by Reinhard Heydrich for his responsibilities in the fine tuning of planned legislation and his experience in drafting anti-Jewish laws. At the conference it had to be established as well which categories of Jews, such as Jews in mixed marriages, half and quarter Jews were eligible for extermination. Since 1940, Kritzinger’s task also entailed Juden und Mischlingssachen (issues concerning Jews and persons of mixed ancestry.

Gerhard Klopfer, close personal friend of Kritzinger and participant in the Wannsee Conference. Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 119-06-44-12 / Unknown / CC-BY-SA 3.0

The participants went their separate ways after they had established the chronological progress of the imminent mass murders. They agreed to work on the final solution under the direction of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA)

Kritzinger’s name only appears on the attendance list of the meeting. His contribution to the discussion is missing from the minutes. It may be he had said nothing but this is highly unlikely. A second reason could be he was too critical about the proposals being discussed and hence his contribution had been omitted on purpose. This isn't likely either because the minutes do show the critical attitude of other participants. Finally, there is the possibility his contribution wasn't sufficiently relevant to be included in the minutes.

The last option seems the most likely as no definite decisions were taken on all sorts of legal issues belonging to his specialism such as the treatment of Mischlinge. To an associate, Kritzinger later described the meeting as Hornberger Schießen, a German phrase meaning something which leads to nothing. As no agreement could be reached about the exact definition of Mischlinge, this issue was postponed and discussed further on March 6, 1942 at a meeting of the ‘experts on Jews’ of the various ministries. There an agreement could not be reached either and that led to a second discussion on October 27, 1942. No evidence can be found in the archives that a definite solution of the issue of the Mischlinge was ever reached.

Kritzinger has been described as participant in the Wannsee Conference as someone who probably felt the least inclined towards the final solution with the most reservations. He is said to have distanced himself internally from the Nazi regime and would have been the only one to be appalled about the proposals to reach the Endlösung by means of evacuation, in other words extermination.

According to the Institut für Zeitgeschichte, a German scientific research institute, like many high ranking officials within the Nazi regime, at the moment of the conference, Kritzinger had no full knowledge of the genocide of the Jews already in progress. This example would show how difficult it was for high ranking officials to get reliable information about the genocide.

In the months after the conference, Kritzinger received information from an associate about the execution of Jews in Poland. He subsequently dispatched some of his officials to the General Government to investigate. They were immediately sent back to Berlin by the police. Moreover, a little later he received a phone call from Heinrich Himmler who warned him in plain language that in the future, such meddling would lead to a one way ticket to a concentration camp for his nosy officials.

Not long after the conference, Kritzinger, who now had more detailed information about the mass extermination, offered his resignation to his boss Hans Lammers in the late spring of 1942. Lammers rejected his request, stating that without his state secretary far worse things would happen: um Schlimmeres zu verhüten. According to him, Kritzinger would be irreplaceable in the continuing struggle of the Reichskanzlei, which was reluctant about the final solution, with the NSDAP where far more radical viewpoints prevailed.

Definitielijst

- concentration camp

- Closed camp where people are being held captive that are considered to be anti- social, enemies of the state, criminal or unwanted individuals. These groups mostly do not get a fair trial or are condemned to doing time in a camp.

- Endlösung

- Euphemistic term for the final solution the Nazis had in store for the “Jewish problem”. Eventually the Endlösung would get the form of annihilating the entire Jewish people in extermination camps.

- invasion

- Armed incursion.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- NSDAP

- Nazi Party, byname of National Socialist German Workers' Party, German Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP), political party of the mass movement known as National Socialism. Under the leadership of Adolf Hitler , the party came to power in Germany in 1933 and governed by totalitarian methods until 1945.

- RSHA

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt. The central information and security service of the Third Reich.

- SIPO

- ”Sicherheitspolizei”. Combination (since 1936) of the Gestapo and criminal police.

- Soviet Union

- Soviet Russia, alternative name for the USSR.

- Wannsee Conference

- Conference at the Wannsee on 20 January 1942. The Nazi’s made final agreements about the extermination of Jews in Europe, the Final Solution (Ëndlösung).

The last years of the war and beyond

During 1942 and 1943, Kritzinger worked on regulations limiting the accessibility of Jews to the courts. This was purely a formality though as the Jews had already been completely robbed of their rights and were being deported. Because his boss Lammers was frequently absent, Kritzinger’s work load increased gradually. In the spring of 1943, he took six weeks sick-leave due to high blood pressure and problems with his eyesight.

On April 20, 1945, with the Red Army already on the streets of Berlin, Kritzinger was ordered to take charge of the evacuation of the ministries and civil servants still remaining in the city. On April 23, he left the capital himself in the direction of Flensburg in northern-Germany.

In May 1945, Kritzinger was appointed State secretary in the so-called Flensburger Regierung, the short-lived last government of the Third Reich after Adolf Hitler’s suicide. The government had its seat in Flensburg and was headed by Großadmiral Karl Dönitz. Kritzinger was taken prisoner in Flensburg by the British on May 23. Initially he landed in PoW camp 32 in Mondorf-les-Bains in Luxemburg where almost all German military and political big wigs had been imprisoned in the Palace Hotel, awaiting transfer to stand trial before the International Military Tribunal. Kritzinger however was transferred to an internment camp in Bruchsal in the vicinity of Frankfurt.

Kritzinger was frequently interrogated by Robert Kempner, deputy of Robert H. Jackson, American chief prosecutor at the IMT. As the only one of the participants at the Wannsee Conference, Kritzinger admitted on his own accord he had been present there. He also acknowledged the criminal nature of the conference. Furthermore, he testified he had been ashamed of the German politics during the war and he admitted that Adolf Hitler and Heinrich Himmler were mass murderers. He told Kempner: ‘The worst for me was the treatment of the occupied areas and of the Jews. I was ashamed to visit the grave of my father.’ He declared he found the deportation of the Jews the worst. ‘Around 1942, 1943 I heard about the deportation of the Jews, of friends from town. Later on, one also heard about it through official channels.’

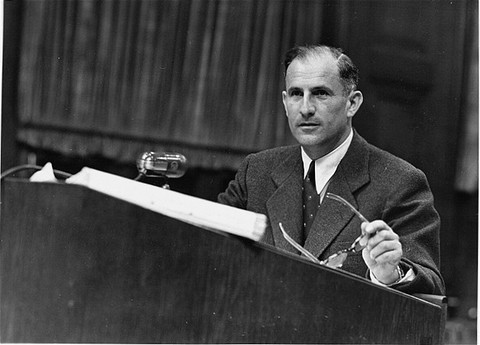

Prosecutor Robert Kempner, who interrogated Kritzinger after his arrest. Source: US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of John W. Mosenthal

Kritzinger described himself to Kempner as a neutral, traditional and conservative Prussian civil servant, not a fanatic political representative of the Nazi ideology: kein Scharfmacher. He declared his profession of civil servant had always been his life’s vocation and he had always been loyal to every government he served. He compared himself to a sailor who didn't jump ship in times of danger, even though the captain was a criminal. Nonetheless and in his own words, he would have been ashamed of his desk job in wartime and had requested to be transferred to the front three times.

Kritzinger was released in April 1946 but in December he was arrested again by the Americans. Due to his bad health however, he was set free again.

Friedrich Wilhelm Kritzinger died shortly afterward in a hospital in Nuremberg on April 25, 1947, the day after his 57th birthday.

Definitielijst

- ideology

- A collection of principles and ideas of a certain system.

- PoW

- Prisoner of War.

- Red Army

- Army of the Soviet Union.

Information

- Article by:

- Robert Jan Noks

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Published on:

- 19-01-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Sources

- JASCH, HANS-CHRISTIAN & KREUTZMüLLER, CHRISTOPH, The Participants, Berghahn Books, New York, 2017.

- KLEE, ERNST, Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich: Wer war was vor und nach 1945, Fisher TB, Frankfurt, 2007.

- LEHRER, STEVEN, Wannsee House and the Holocaust, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, North Carolina, 2000.

- LONGERICH, PETER, De Wannseeconferentie, Spectrum, Houten, 2018.

- MIXON, JR., FRANKLIN G., A Terrible Efficiency, Palgrave MacMillan, Cham, 2019.

- ROSEMAN, MARK, The Villa, The Lake, The Meeting, Penguin Books, London, 2003.

- de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich Wilhelm Kritzinger (Ministerialdirektor)

- de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reichskanzlei

- de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verordnung gegen Volksschädlinge

- de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reichsbürgergesetz Elfte Verordnung vom 25. November 1941

- de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nürnberger Gesetze

- nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelm Kritzinger

- www.ghwk.de/de/

- www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/friedrich-wilhelm-kritzinger

- www.deutsche-biographie.de

- www.yadvashem.org

- de-academic.com

- nl.findagrave.com/memorial

- www.bundesarchiv.de

- www.memoiresdeguerre.com

- en-academic.com

- berghahnbooks.com