Introduction

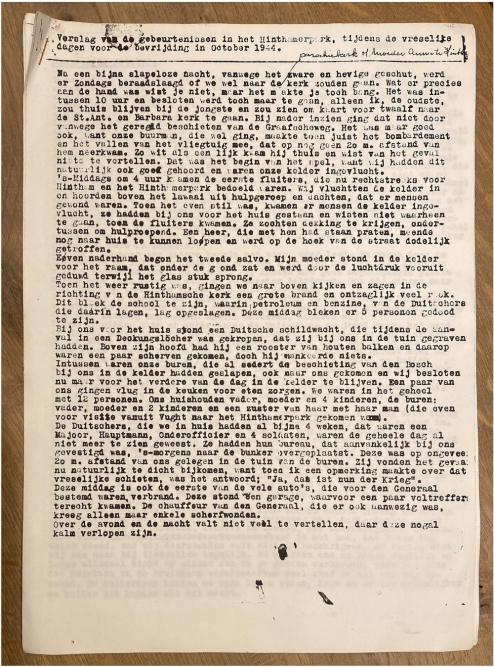

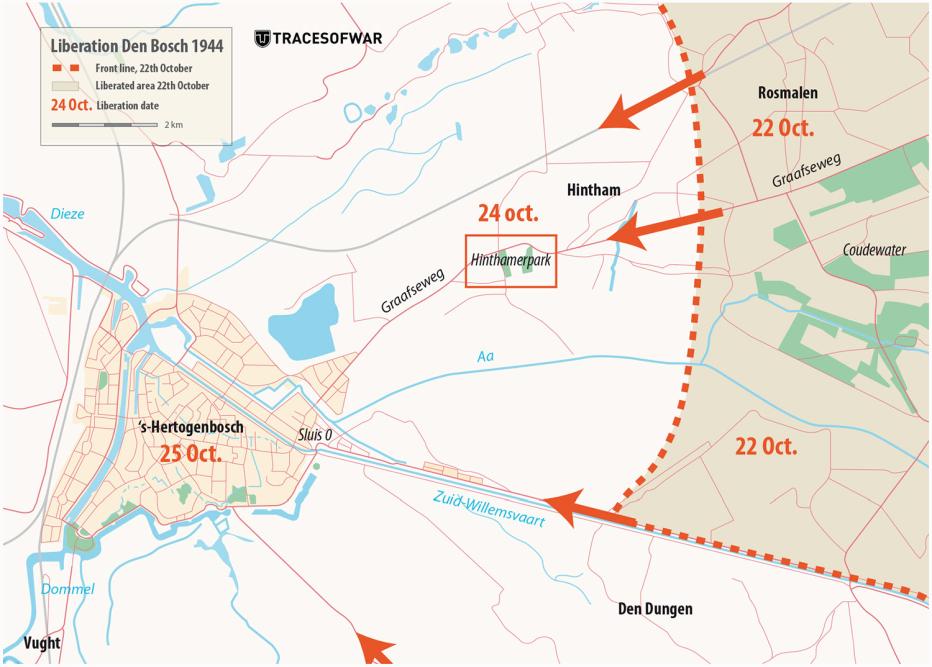

The following text was found in a small notebook written by Mrs M.A. Bogaerts-Bechtold (born August 10, 1925 and died November 9, 2013). She resided with her parents in the Hinthamerpark in Hintham, a district of Den Bosch/ ‘s-Hertogenbosch, and spent many frightening hours in the basement of her parental home during the battle of the liberation of the city. The story takes place in the period of October 22 to 24, 1944. Den Bosch was eventually liberated on October 27. This text is largely the same as the original text, aside from some textual improvements. Comments by the editorial staff are written between square brackets.

Sunday, October 22

After a night that was almost sleepless due to the intense and heavy artillery, there was deliberation whether we would go to church, the parochial church H. Mother Anna in Hintham. You did not know what exactly was going on, but you were still afraid.

In the meantime, it was 10:00 o’clock and it was decided that we would go to Church. Only I, the eldest, would stay home with the youngest and I would go to the St. Anna and Barbara Church at 11:45. On second thought, that did not happen due to regular shootings of the Graafseweg. And it was a good thing because our neighbour, who did go, witnessed the bombardment and the crashing of a plane not even twenty yards from him. He came home as white as a sheet and he did not know how to talk about the crash. This was the beginning of the game, because of course we had heard it as well and had fled into our basement.

In the afternoon at 16:00, the first ‘whistlers’ [= grenades] aimed at Hintham and Hinthamerpark were launched. When it was quiet for a short while, people who had been standing in front of the house because they did not know where to go when the ‘whistlers’ were launched, fled into the basement. They were looking for shelter, while calling for help. A gentleman who had been talking to them and believed he would be able to walk home was mortally hit on the corner of the street.

Just a little later, the second salvo began. In the basement, my mother stood in front of the window under the ground, which bulged outwards due to the air pressure while the glass burst into pieces.

When it was quiet again, we went and looked above and saw a large fire and a massive amount of smoke in the direction of the Church of Hintham. This turned out to be the school, in which petroleum and petrol, belonging to the Germans who were lying inside, were stored. Five people turned out to have been killed that afternoon.

In front of our house stood a German sentry who had crawled inside a Deckungsloch [= foxhole] which they had dug in our yard. He held a grate made out of wood above his head and a few shards had landed onto it, although he came out unscathed.

In the meantime, our neighbours, who had slept alongside us in our basement ever since the beginning of the shooting, had also come over to us and we decided to remain inside the basement for the rest of the day. A few of us quickly went to the kitchen to get food. There were twelve of us in total. Our household: father, mother, and four children; the neighbours: father, mother, and two children and a sister of hers with her husband (who had come to visit the Hinthamerpark from Vught).

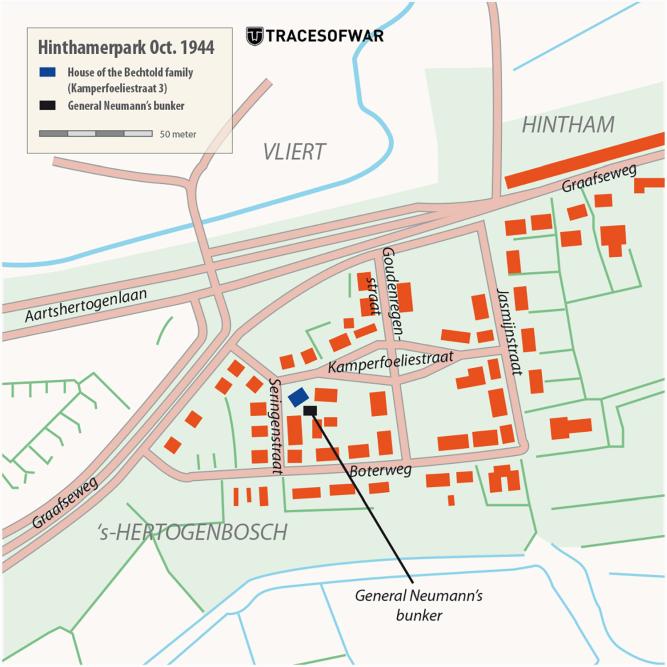

The Germans who had been in our house for four weeks, consisting of the major, Hauptmann, non-commissioned officer and four soldiers, had not been seen for the entire day. That morning, they had moved their office, which had earlier been situated at our place, to the bunker. The bunker was situated about twenty yards from us in the garden of our neighbours. They of course considered the danger too close by because when I made a comment about the horrible shootings, their response was: “Yes, that is war for you.”

That afternoon, the first of many cars meant for the general, was burned. It was standing inside the garage in front of which a few direct hits landed. The driver of the general, who was also present, only received some fragment wounds.

There is not much to say about that night, because it went by relatively quietly.

Monday, October 23

This morning, the sister of our neighbour left with her husband because they of course preferred to be in their own house, and also because of the recommendations of the Germans. They had said, “that they should go home as quickly as possible.” Just a little later, one of the boys from our neighbours across the street came to tell us that his fifteen-year-old brother had most likely been killed by the artillery fire yesterday in the afternoon. He had left to take a look at the crashed plane with another brother and friends when they were surprised by the shellfire. “They all came home unharmed, except Gerard,” our neighbour told us, and they went to look for him, but without any results and the entire night we have been in distress. This morning, my oldest brother went to the hospital to seek information and a boy who matched Gerard’s description had been brought in yesterday. He was already dead and now we are afraid to tell our parents. Then the father arrived, desperate and unsure what to do. He decided, as he told my father, to take his entire household to Den Bosch, take their bedding and clothes, sleep inside the Brandwaarborg [a cooperative non-life insurance] and then look for information about Gerard. His oldest son had told him a half-truth. Looking back, the boy may have saved the lives of his entire household because had they stayed home, they would have gone inside their basement which had collapsed.

After them, another acquaintance came with another kind of grief. They had been kicked out of their basement by the Germans and they had to seek shelter somewhere else with their four children. It was impossible for us to make space for them, for we ourselves already had to sit really close to each other. They also went to Den Bosch and that night, their house also burned down.

That is how the morning went by, with only heavy artillery in the distance. The children played in the basement and we meanwhile took care of lunch, which we would have to do without for God knows how long, we thought.

By noon, the Germans finally undertook action and sure thing, the gentlemen probably sensed the net was closing in, and they left. They said they went to the fraterhuis in Den Bosch (afterwards it turned out they had been in a bank building) and if we were afraid we could join them, there was enough space. But of course we rather stayed home, for we had a good basement and thought the biggest danger had passed now that we saw all those Germans leave.

Only General Neumann (https://www.tracesofwar.nl/persons/8218/Neumann-Friedrich-Wilhelm.htm) stayed only to eventually also leave as the very last person. He had taken possession of the bunker next to us for such a long time. In total, there were now maybe fifteen Germans left.

19:00 at night

Now, all hell broke loose. A few soldiers who had returned to retrieve some items, fled into our basement with us. The noise was far worse than the day before.

Suddenly, we heard a sound of breaking glass and something landed on the floor with a heavy thud. A piece of the gutter had broken off. When it was silent, we all heard ticking and something walking, and although that was only the water from the gutter, every noise made us nervous. Now, the Germans took the opportunity to go back to Den Bosch, although before they left, one of them said: “If all of you still got your head on your shoulders by tomorrow, you should be happy.” Those were some “cheerful" words, but we still could not see things that negatively.

20:00 at night

For the second time the same thing occurred. Then, the first impact also happened in our kitchen and after all, it was still standing although the entire house burned to the ground, except the kitchen, which was probably caused by the bathtub upstairs, which was filled with water. What we went through is indescribable, they fell down not one by one but with dozens at the same time. We made ourselves as small as possible and we lay close to each other with our faces hidden, because the debris that fell down and the gunpowder caused much dust which created a feeling of stuffiness. We had left the basement door open, so we could more easily leave the basement if we had to.

Up until 22:00, a new salvo was discharged every fifteen to twenty minutes. Worst of all, we could hear the shots so well that we wondered, were they once again aiming at us? We were waiting, filled with anxious tension. We did not even know during each salvo whether our house had once again been hit, that is how intense it was. When it was silent, we heard crackling and banging sounds outside, which also made us frightened. Father crawled on his hands and feet outside the basement to take a peek. It turned out to be cars, parked a little farther away. They had caught fire and probably had hand grenades and munitions inside them, which naturally caused such a blazing fire. The flames and pieces flew high and far away and that could possibly also be why several houses caught fire. At first, we thought our house was also on fire due to the crackling sounds and we asked the batman of the general, who was searching for the driver but had fled into our basement during the rain of grenades, if he wanted to take a look. Before I continue, I should note that the man was incredibly nervous and scared. He was not even upstairs yet when he screamed: “There is a fire up here.” We jumped up and stood ready with everything we needed to take with us in our hands, when father took charge. He went to take a look for himself and returned with the reassuring message that it was a false alarm. As the kitchen was already very broken, the light of the burning houses behind us shone onto the wall tiles, which was mistaken for fire. Thank God, on one hand, that was an assurance, but on the other hand, we were now again scared that our house would catch fire. The two mothers were hell-bent on fleeing to Den Bosch, but I would have never done that.

Imagine you were on the Graafseweg and yet again another one of those salvo’s was fired. Where would you go with the children? Fortunately, the men knew how to get it out of her mind, although it was not an easy task. Thank God it stayed silent for a while now and father took the opportunity to crawl on his hands and feet to inspect the entire house and pull the curtains from the windows to prevent possible fire hazard, and he brought the pram from the attic so we could use it if we had to flee. Father told us that the attic was ravaged due to various direct hits. Suddenly, the peace was disturbed by the sound of a car. Father went to take a look and saw that it stopped in front of our house. At the same time, father saw that the general and his followers were ready to get in the car, and he also heard new salvo’s being fired. He was just in time to see them flee back to the bunker, but then my father also quickly made his way back to the basement. This was around 10:30.

Group photo of the general staff stationed at Seringenstraat 1 in Hintham (near the bunker). It was sent to the Bechtold family by the widow of Count Hochberg, who was killed near Berlin in April 1945. On the back of the photograph are the names of the soldiers. From left to right: Hauptmann Möhn, Major Bertenrath, Lt Bechold, Lt Buske, Major i.G. Wentzel (in profile), Lt ?, General Neumann, Hauptmann von Kalkreuth, Major Gräf Hochberg, Lt Schmidt, Oberst Dr Schott.

With this new rain of grenades, three other Germans fled into our basement. They told us they had experienced the same thing the night before in Schijndel. They said that they had fled from that hell in the morning, and travelled past St. Michielsgestel and Vught to Den Bosch to look for their troops. They did not know where they were and had therefore made a big detour and consequently walked straight into the hands of the English. There was a seventeen-year-old boy who had only been serving for twelve weeks yet was already at the front, and he was sick and tired of it, and so were the others. They told us the Tommy’s were near and that we would soon be liberated. We also experienced this in Schijndel, we are unable to do anything under artillery fire, and when it is peaceful, we take the opportunity to withdraw.

Tuesday, October 24

Around noon the drumfire broke loose, and it lasted until around 16:00. We could not go upstairs to take a look during the drumfire, because direct hit after direct hit landed on our house. They were horrific, indescribable hours, we had not experienced it to be this bad. The electric light, which had already been burning weakly the entire time, also went out now. We could not keep the candles on. That is how we were sitting there in the dark. We cringed in fear during each salvo, even the Germans were laying with their faces covered in the blankets. They said they had not experienced anything this bad, not even in Schijndel. At some point a hole was slammed into the sidewall, right across the basement entrance, so we could look outside from the basement.

This was terrifying, for we thought: If the next grenade lands on the same area, it will end up in the middle of the basement and we will all be doomed. At around 03:00 we noticed that our house was on fire (fortunately my father carried his watch) but there was no possibility for us to leave the basement, for the drumfire blocked the only exit that was left of the three exits we used to have. We stayed in the basement until the bedding caught fire. The two mothers kept calling to my father: Help us please, help us, please, think about the children.

Another one kept saying prayers and the third screamed: “O guys, just stop shooting, has it not been enough?” But none of it helped a single thing. I heard mother say: “O Mary, I have always said my prayers, that our house would be spared, it was not supposed to be I guess, if only you could save our lives now.” Father then made a decision: He’d rather be killed by shrapnel than be burned alive. What would otherwise not succeed, was now possible. He pulled a basement window out, which was still hanging from its hinges, hinges and all using no tools. He then had to remove an iron grid from the cellar hole outside, in which he succeeded in after some effort. We watched father’s work with breathless tension and despite the continuous fire, it appeared we were not as scared anymore. I had my three-year-old little sister on my lap wrapped entirely in a blanket, and because she was quiet as a mouse, I kept speaking to her because I was afraid that such a little one would choke in the smoke, for it was incredibly stuffy. It was remarkable that we all remained perfectly calm and did not cry or scream at all, both young and old. It appeared that we had surrendered ourselves completely. We still cannot understand that the little children heard nothing, absolutely nothing that entire evening, that long night and the following morning, although they should have heard the thundering violence that we adults were so afraid of.

Suddenly father called out: “We have been saved.” He was laying flat on the ground against the wall. While the shards and burning pieces of the house were falling all around him. We saw glowing debris fly past the basement window. One of the Germans stood at the basement window to hand the children over while the others were stomping on the blankets, which had already caught fire. My fourteen-year-old sister was the first one to leave the basement. Father brought her to General Neumann’s bunker which was about twenty yards away. The sentry prohibited her entrance, although father just pushed her inside and he crawled back himself to get the others. It was now the youngest child’s turn and miraculously, the shellfire suddenly stopped.

We all came out of the basement unscathed now, but it was also high time. We were unable to take any of the items that were standing or hanging in the kitchen, because we considered every second was counting, soon enough they would start shooting again. When it was my turn to go to the bunker, I could not find the way, which I could normally find with my eyes closed. It was night, the entire park was brightly lit due to the burning houses and two floodlights were directed at our park. They let us freely inside the bunker now. How happy we were that up until this moment, we had all come out unscathed and were safe again for now. One of the three Germans asked father whether we were all together now and no one was possibly still in the basement. I saw that the driver of the general had my youngest sister on his lap, and that the little one had nicely fallen asleep. The general himself was asleep. We had to be motionless and were afraid to move a muscle. It was packed in the small bunker, other than our group consisting of ten people that joined the three Germans and the general, there were at least nine other Germans present.

Shortly after we had entered the bunker the neighbour, who is a widow with four children, fled into the bunker. She had spent that terrible night alone with her children in a cellar cupboard of the house. But now, it became too much for her. She addressed my father: “Oh sir, I do not know who you are (it was dark inside the bunker) but would you keep this for me, I do not know what it is, but I will get it back from you later.” Afterwards, it turned out to be a pair of stockings and some children’s underwear. We had a good laugh about it later on though. It was suffocating, everything was locked down and we were hanging more than we were standing. We had to survive in this position for two hours. Fortunately, it had been quiet all this time. That was a stroke of luck, because most of us could no longer stand inside and consequently had to stand in the small corridor of the bunker, which had only been reinforced halfway. Outside, we now only heard the crackling of our burning house. When the general woke up he took our little neighbour boy on his lap. A liaison officer came by a few times to deliver messages and he had to pass on over our heads. Around 17:30, we heard the general and his officers deliberate.

General Neumann himself wanted to stay, because all the roads were blocked. One of the officers said: “We are going, we have to.” “All our cars have been burned”, the general responded. “Then we will walk,” the stubborn officer said. “All right, but then we will arrive in Den Bosch with broken arms and legs,” the general responded to this idea. During his departure he expressed his sorrow to my father, for what we have gone through and lost that night.

German general Neumann's destroyed Borgward service car in the destroyed Hinthamerpark. Source: Erfgoed ‘s-Hertogenbosch

Once they had left, we had the bunker for ourselves and we had to wait and see. We did not know anything and were just sitting there very quietly on the couches, exhausted and dazed, no one said a word. Every now and then grenades would fall, and although we would still cringe, it did not compare to last night. It started getting light outside. Every now and then we heard machine-gun fire and father said the Tommy’s could now not be too far away. He once checked around the corner of the door and returned with the words: “It is the most beautiful weather of the world, but everything surrounding us gives it such a terribly bleak appearance.” It was completely silent everywhere, you only heard the chirping of the little birds and the cackling of the chickens. There was not a soul in sight outside. We were really in no-man’s-land now and we thought that we were now the only ones left in Hinthamerpark.

The night had been horrible, but that morning was also unforgettable. There was no food, nor drinks and the little ones asked for it. The two fathers searched everywhere and found two slices of bread in a corner. These were divided among the three smallest, who were a child aged one (he had celebrated his birthday in the basement on Sunday) and two children aged three. Needless to say, this was not enough for them. We also found a little bit of wine, which we gave to the children one by one. As you can understand, we were naturally all incredibly thirsty. The mouths were dry and the large amount of dust caused sore throats. How much longer would this continue, a day, two days? We did not know and spent the rest of the time motionless again, because we did not feel like talking, it made you so tired.

Around 23:00, my father took another look and he returned excitedly. “Sst. shush”, he said, “I saw a Tommy, he came right past here. I was afraid to call him, for he was standing with his back to me and I was afraid I would startle him and he would shoot.” We were happy that we now had certainty that our rescue was near. We searched for something white, which could serve as a white flag, and we bound it to an ax, which we placed outside. We checked in half an hour later and saw some English standing in the courtyard with radio-installations on their backs, and some citizens who had come out of their several bomb shelters surrounding them. The first thing father took care of was food and drinks, which he borrowed from acquaintances. Although we could not eat, we could at least now take care of the children. We also spoke to our neighbours and that is how our mutual experiences were hastily told. This way we also heard from one of our acquaintances that she had saved furniture during the shellfire when their house was on fire. Everything was standing outside. During the next rain of grenades, it suffered a direct hit and everything was gone. That is how we heard about each other’s grief.

It was terrible to see what our park looked like, you could not imagine that something like that had happened in the span of a night. You can understand that we wanted to leave this misery. There was not one piece of ground that was not affected by a grenade. There was rubble, stone, and holes everywhere. We borrowed a bike and a pram from friends and went to Rosmalen. It was very busy on the road with transport, you really had to watch where you were walking and everyone stopped us and asked how we had endured it, and then the first tears came. The grenades were now flying over us, but we were still very afraid of them. It was all very exhausting and we longed for nothing more than rest and a roof above our heads. In the meantime, we saw tanks and cars drive up against the rail embankment and over the rails further down the direction of Den Bosch. To make matters worse, we also saw many dead soldiers and animals along the road, what a horrible image. The road was littered with small, venomous pieces of shrapnel that have killed so many.

Anyway, that is how we at long last arrived at our friends, where the ten of us were received with open arms. Fortunately, they had not suffered any damage. But they did tell us later on: Had we not known you, we would have almost sent you away, that is how you looked, dirty, decayed, and almost like gypsies. No wonder. We had noticed this about the little ones, but we did not notice it about ourselves. Our hair was stiff from the rubble and dust that was in it. You almost could not hear my father, he was that hoarse. Our neighbour was wearing his pyjama top underneath his jacket instead of a shirt, and my father was walking around in a shredded suit without a coat.

We stayed in Rosmalen for three weeks and we got some rest there. When the opportunity arose, we went back to Den Bosch and we hope that soon the time will come for us to return to our Hinthamerpark.

’s-Hertogenbosch Nov/Dec 1944

Information

- Translated by:

- Sebastiaan Berends

- Published on:

- 04-05-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related books

Sources

- Backus, Paul / Willem Cornet / Toon van Gent / Frank Roose, Hinthamerpark in oorlog, documentaire over de Hinthamerparkwijk in Den Bosch ten tijde van de Tweede Wereldoorlog uit 2008.

- Brabantinbeelden.nl

- De bevrijding van Den Bosch (2-delige documentaire), op: Youtube (1) en Youtube (2)

- De strijd om Brabant, 20 oktober – 9 november 1944

- Erfgoed ’s-Hertogenbosch, De bevrijding van ‘s-Hertogenbosch

- Omroep Brabant, Diezebrug opgeblazen en lijken ontdekt in de polder