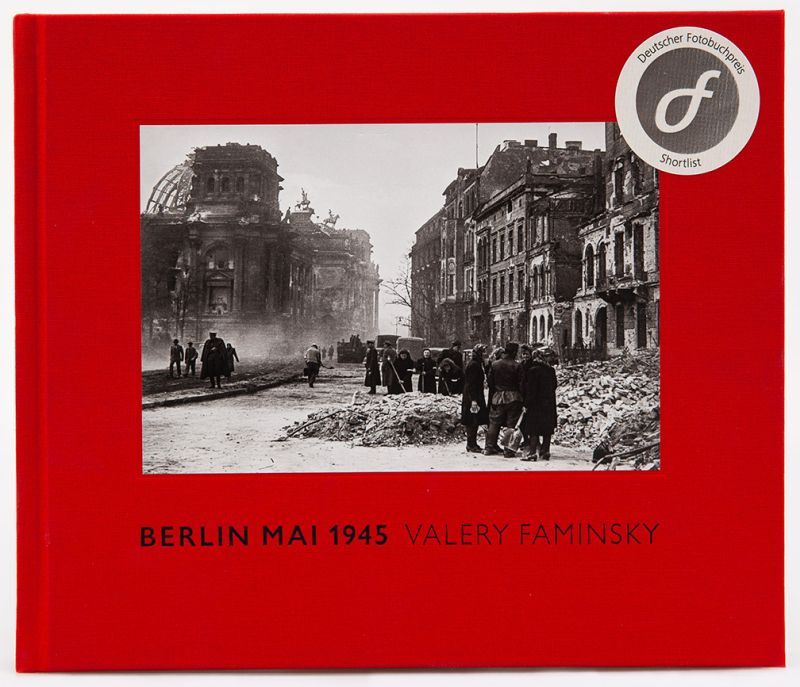

| Title: | Berlin Mai 1945 - Valery Faminsky |

| Writer: | Faminsky, V. |

| Published: | Buchkunst Berlin |

| Published in: | 2020 |

| Pages: | 184 |

| Language: | German |

| ISBN: | 9783981980585 |

| Description: | Valery Faminsky (1914-1993) was a Russian photographer. He first trained as a locksmith in the workshop Aviachim-Fabriek Nr. 1, a motorcycle factory that was located in the workshop of the Aviachim aircraft factory. Because of his poor eyesight, he soon had to stop and became a photo assistant in the photo lab in the same factory. That was more in line with his interests, because he had already discovered photography at the age of fourteen. Within the factory he founded a photo club to interest others in photography as well. Barely twenty years old, Faminsky was appointed leader of the photo lab. In the years 1936-1939 he was the regular photographer for an agricultural exhibition in Moscow and from 1939 to 1941 he worked for the planetarium in Moscow. When Russia was attacked by the German army in June 1941, Faminsky was exempted from military service, again because of his poor eyesight. It enabled him to evacuate his relatives and other persons from the capital to Kemerowo, a town deep in the Russian hinterland. He also helped his stepfather, the painter N.G. Kotow (1889-1968), who was active at the headquarters of the partisan movement. From July 1941 to June 1943, Faminsky was employed as a photographer for the NKVD, the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, in the Kererovskij district. The powerful NKVD department became known by the Chief Directorate for State Security (GOeGB), which was responsible for internal security (tracking down "enemies" at home and abroad). In 1954 it would be split up into, among others, the KGB. In June 1943 he returned voluntarily to Moscow to report for military service. He started training as a telegraph operator. In November 1943 he started working as a photographer for the Military-Medical Museum of the Red Army, for which he provided photographic documentation of the war actions on seven fronts during the Second World War. In the period April-May 1945 he photographed on his seventh front: the suburbs and city centre of Berlin, which was then completely in ruins. He returned home at the end of May 1945 and was demobilized in August 1945. From 1946 he worked as a photographer for the Moscow department of the National Art Fund. Although Faminsky's work had not completely fallen into oblivion afterwards, there was not much interest in it either. Arthur Bondar (1983), a Ukrainian freelance photographer who worked for many important international magazines, wrote in a foreword to the book how he discovered Faminsky's photographic work. In 2016, he saw an advertisement offering negatives from a Russian war photographer. The ad turned out to come from relatives of Faminsky, who had died thirteen years earlier. Since then the family had managed his artistic estate and tried to sell it to a number of museums. Although they were interested, they lacked the means to purchase. People wanted to accept the negatives as a gift, but the family decided against that. Bondar quickly realized, after examining the photos, that he was dealing here with work that was beyond the usual Russian war propaganda work. He made a purchase, scanned the entire archive and managed to interest Buchkunst Berlin in arranging for a publication of Faminsky's work in May 1945 in devastated Berlin. Valery Faminsky, 31 years old when the Russians laid siege to Berlin in April 1945, was commissioned as a photographer to provide documentation of the medical facilities for wounded soldiers and the functioning of these facilities. At the time, he was already an accomplished photojournalist. He had been active at the front in Belarus (December 1943), witnessed the liberation of the Crimea (April 1944), was there when Bulgaria was liberated (June 1944) and when the Germans were expelled from the Ukraine (August 1944 ), witnessed the bloody liberation of Poland at the front (March 1945) and was now in Berlin to document the last battles of the Second World War (April-May 1945). His military accreditation allowed him to move freely throughout the city, experiencing first-hand the total collapse - physical, psychological and ideological - of the Nazi dictatorship. In the first days of May 1945, the war in Europe was over. In Berlin, too, the guns were silent and everyone prepared to lick the wounds and resume normal life. 175,000 German and Russian soldiers lost their lives in the battle, while 20,000 civilians were also killed. The number of injured ran into the hundreds of thousands. Faminsky did what a photographer does: he took pictures. If one looks at the photo work in this book, one can see here and there that his work as a propaganda photographer is not quite finished. Generals posing while looking over a map of a front that is no longer there. Soldiers proudly standing at attention in front of buildings that have been destroyed. A group of Soviet soldiers, all with at least one medal, who receive political information from their officer. A general visiting wounded soldiers. A number of Soviet soldiers in a cosy, homely atmosphere, with one of them putting on a different gramophone record just then. However, it is also clear that Faminsky had taken the liberty of withdrawing from the propaganda goals for which he was originally hired. Like a true documentarist, he photographed daily life as he found it in the city of Berlin without making a distinction between Russians and Germans, between soldiers and civilians, between official affairs or daily life. Here and there some soldiers are still sitting by their tanks, the barrel of which has already been packed because further service is unnecessary. Others clean their guns and yet another drags a wounded comrade on a rickety cart to a hospital. The photos of various hospital barracks bear witness to the primitive conditions under which operations had to be carried out. Where the injured lie on the ground, with a sloppy bandage strap to stop the bleeding. A horse staring at the photographer almost pleadingly in an otherwise almost deserted street, its neck bandaged. A Russian announcer who addresses to a youthful audience that Germany capitulated unconditionally in Reims the day before. Berlin citizens on their way to better places or in search of food, a dull look in the eyes, Russian soldiers taking the opportunity to paint a painting of Berlin's ruins. The work of Faminsky and the care provided by the publisher are praised in the international media. Rightly so, because the photos are often of exceptional quality. It is then pointed out that Faminsky, who as an employee of the infamous NKVD was a remarkable "embedded photographer", who had the exceptional ability not to take sides in his photo work. Both victors and vanquished are treated the same way. The misery of both parties is shown, but also the way in which everyone is carefully looking to the future again. That is indeed not common for a war photographer, because normally he only works at the front and only records combat actions. In the case of an NKVD photographer, nothing but heroic images of a victorious army. It is almost impossible for all of Faminsky's work on the other fronts where he worked to provide such a one-sided overview. However, the photographer was now in peacetime and he simply photographs what comes in front of his lens. The question remains how these photos were received within his Stalinist position. Probably good, because he did not disappear nameless in the Gulag archipelago and after 1946 was able to resume his career as usual. The fact that Faminsky photographs wounded soldiers in pitiful field hospitals can also be explained as an example of the unyieldingness of the Russian people and of the many sacrifices made during the long war years. It also shows that the war is not only heroic, but it comes at a high price. After all, that was also a story that the Soviet Union wanted to propagate in the post-war years. A high price that was also paid by the Berliners. His photos of the German survivors show people's resilience, but at the same time they show that the hostile nation has been completely defeated, that its capital is completely in ruins. The individual citizen is mainly seen as a victim. These civilians and the wounded Russian soldiers symbolize the eternal victim of all wars that are planned and carried out at the state level. The continuation of diplomacy by other means, as Von Clausewitz once put it. However, that is the modern interpretation of Faminsky's work, because given his background, it is very doubtful that he ever wanted to show this humanist philosophy in his documentary. In fact, would dare to show if he was unsure of his superiors' approval. However, photographs take on a life of their own over the years, regardless of what the photographer and his client originally intended with them. Faminsky has made a propaganda documentary in which the victors and the vanquished are shown. With compassion for both sides, but in essence a Russian winner and a defeated German population. Now, over 75 years later, they take on a deeper meaning and give a good picture of the situation in Berlin in May 1945 and thus symbolize the real victims of all wars. The work has therefore become an impressive document. |

| Rating: |     Very good Very good |

Information

- Translated by:

- Sanjay Bhoep

- Article by:

- Frans van den Muijsenberg

- Published on:

- 24-12-2020

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Images

Bron: Valery Faminsky / © Arthur Bondars Private Collection..

Bron: Valery Faminsky / © Arthur Bondars Private Collection..

Bron: Valery Faminsky / © Arthur Bondars Private Collection..

Bron: Valery Faminsky / © Arthur Bondars Private Collection..

Bron: Valery Faminsky / © Arthur Bondars Private Collection..

Bron: Valery Faminsky / © Arthur Bondars Private Collection..

Bron: Valery Faminsky / © Arthur Bondars Private Collection..

Bron: Valery Faminsky / © Arthur Bondars Private Collection..

Bron: Valery Faminsky / © Arthur Bondars Private Collection..

Bron: Valery Faminsky / © Arthur Bondars Private Collection..