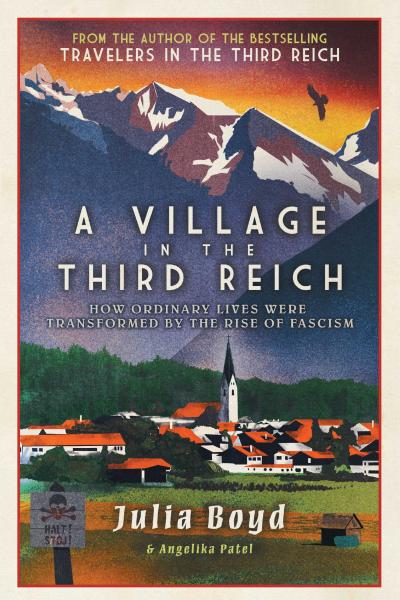

| Title: | A Village in the Third Reich - How ordinary lives were transformed by the rise of fascism |

| Writer: | Boyd, J. & Patel, A. |

| Published: | Elliott & Thompson |

| Published in: | 2022 |

| Pages: | 412 |

| Language: | English |

| ISBN: | 9781783966561 |

| Review: | Oberstdorf is a German village in south-west Bavaria that has all the necessary elements to look good on a postcard. Surrounded by majestic mountains, it drew plenty of tourists even in the last century. One of them was Queen Wilhelmina, who spent her holidays here in the pure Alpine air in 1930. Sports enthusiasts were also finding their way to the popular holiday resort to explore the mountains with sturdy hiking boots, climbing equipment or skis. During the period 1933-1945, however, this idyll could not escape the Nazi dictatorship. The town council, the village school and all associations had to conform to the laws and dictates of the National Socialist government. Villagers who refused to conform risked being betrayed by their neighbours and ending up in a concentration camp. In wartime, young men from the village were sent to the front, from which many never returned. This threatened to disintegrate village society and even decades after, people would rather not mention this difficult time. In A Village in the Third Reich, the British Julia Boyd describes how radically the lives of Oberstdorf residents changed under the rule of Hitler. She was assisted by Angelika Patel, born in the village, and author of Ein Dorf im Spiegel seiner Zeit: Oberstdorf 1918-1952. Before that, Boyd published the well-received book Travellers in the Third Reich, about the experiences of international visitors to Germany in the 1930s. In this book, she illustrated how indifferent and sometimes even admiring foreigners viewed the social changes they perceived in the Third Reich. In contrast, her new book is predominantly about the experiences of Germans themselves, mainly the inhabitants of the Alpine village. Their reactions to the Nazism varied more than one would expect in a dictatorship. For example, we get to meet a postman who was a fanatical Nazi from the outset and founded the local branch of the NSDAP in Oberstdorf, but also the high school headmaster, who tried to find a happy medium between his humanist ideals and Nazi doctrine. Others, like the village priest, rejected National Socialism, although they had to conceal their views to keep out of trouble. Before Boyd starts describing Oberstdorf between 1933 and 1945, she first paints a picture of the village in the post-World War I era and about how the population reacted to the political uprising of the Nazis. It was not a bastion of fanatical Hitler disciples. Both because of their Catholic faith and the tourism in the village, many villagers were careful to keep their distance from the Nazis. The local middle class profited financially from Jewish tourists and was thus not keen on Hitler's rabid anti-Semitism. Nevertheless, when the dictator came to power in 1933, the so-called Gleichschaltung unfolded at lightning speed in the Alpine village. There came a Nazi mayor, associations included in their statutes that Jews were no longer allowed as members, and children joined the Hitlerjugend. On a postcard, there was a picture of the village with a swastika shining like the sun in the background above the mountains. Whereas before 1933 the local newspaper hardly covered the Nazis, suddenly the pages were brimming of articles that were always positive about the new regime. There was considerable mutual distrust, as fanatical Nazis were not afraid to betray their fellow villagers. For example, an innkeeper was reported for illegally slaughtering cattle by a fellow villager, who served as meat inspector, and narrowly escaped imprisonment in a concentration camp. Many young men from Oberstdorf served in the Wehrmacht's 1. Gebirgs-Division during wartime. Drawing from diaries, the author paints a picture of what it was like at the front. She also recounts how the mayor personally shouldered the task of reporting the death of soldiers to their parents or wives. The remarkable thing about this mayor appointed in 1934, the chimney sweeper Ludwig Fink, was that although he was an enthusiastic National Socialist, he protected several persons in need, including Jews. One of them was a miller, widely respected in the village, whose Protestant wife had died, resulting in him losing his protected status as an intermarried man. Fink managed to protect him for a long time, until the man received a notice of deportation to the Theresienstadt ghetto and committed suicide. Similarly, there was no salvation for Theodor Weissenberg, whom the author commemorates in a separate chapter. Born in Oberstdorf in 1921, the young man was the grandson of a former mayor and, because of his blindness, was murdered by the Nazis in 1940 in 'euthanasia' centre Grafeneck, about 150 kilometres north of his birthplace. There was no place for people with disabilities like him within the 'genetically healthy' German population. Fink's own son, who suffered from epilepsy, was spared this fate because his parents brought him home in time from the institution run by nuns, where Theodor also stayed. One Oberstdorf resident of interest to Dutch readers is writer and benefactress Henriëtte ('Hetty') Laman Trip-de Beaufort. After being widowed in 1928, this noble childless lady ran a children's sanatorium called Hohes Licht in Oberstdorf, which she set up in the 1920s. She worked on a friendly basis with the German director, Elisabeth Sophie Dabelstein. Both women wanted nothing to do with the Nazis and, despite being forbidden to do so, also took Jewish children into their sanatorium. They registered them as 'Aryan'. Then, the sanatorium served as a link in a smuggling route by which Jewish children were taken to Switzerland. Hetty also smuggled food, clothing and other supplies to Dutch prisoners and forced labourers who were staying in camps near the village. After the war, Hetty was decorated for her good deeds in the Netherlands as an officer in the Order of Orange-Nassau, Elisabeth as a knight. The actions of both women are granted the attention they deserve in this book. Proof that in a wartime German community everything is not quite as straightforward as one might think is also provided by the creation of the Heimatschutz towards the end of the war. Oberstdorf residents formed this resistance movement to ensure that their village could be conquered by the Allies without bloodshed. They captured some potentially dangerous villagers. When the first French troops reached the village on May 1, 1945, Oberstdorf was taken uncontested. The front troops were replaced by French-colonial Moroccan troops after a day. The men with their red fez and dark skin colour initially frightened the locals, but they turned out to be friendlier than the resentful French. A German soldier who returned to the village and saw that his wife shared the house with Moroccan soldiers immediately became good friends with the foreigners to whom, to their delight, he showed his photographs of his mountaineering exploits in their homeland. However, the occupiers commandeered many cattle, whose meat they roasted over small campfires they lit throughout the village. Meanwhile, the food supply situation for the locals kept on worsening. Moroccan forces had to step aside to make way for American troops on July 7. The book also covers the first post-war years in Oberstdorf. At that time, hunger was high and those who had been members of the NSDAP or another Nazi organisation were subjected to denazification, which was relatively mild here. The conclusion comprises the establishment in 1949 of the Federal Republic as a sovereign state. The writer gives a summary of all the featured villagers, and briefly summarises their lives. This is how we also find out how they fared after the war. Additionally, the book contains some geographical maps and a map plus a photo section. The fact that much source material has been preserved, partly because the village was never struck by the violence of war, was an advantage for the author. For anyone interested in the effects of historical events on the lives of ordinary people, A Village in the Third Reich is an essential book. Oberstdorf serves in this book as a microcosm within the Third Reich where not everything happened as you would expect based on the surface. Julia Boyd shows that even in this village in Nazi Germany, the boundaries between right and wrong were blurred and that it is simply unsustainable to view Germans only as a nation of villains. |

| Rating: |      Excellent Excellent |

Information

- Translated by:

- Sophie Louwers

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Published on:

- 14-03-2024

- Feedback?

- Send it!