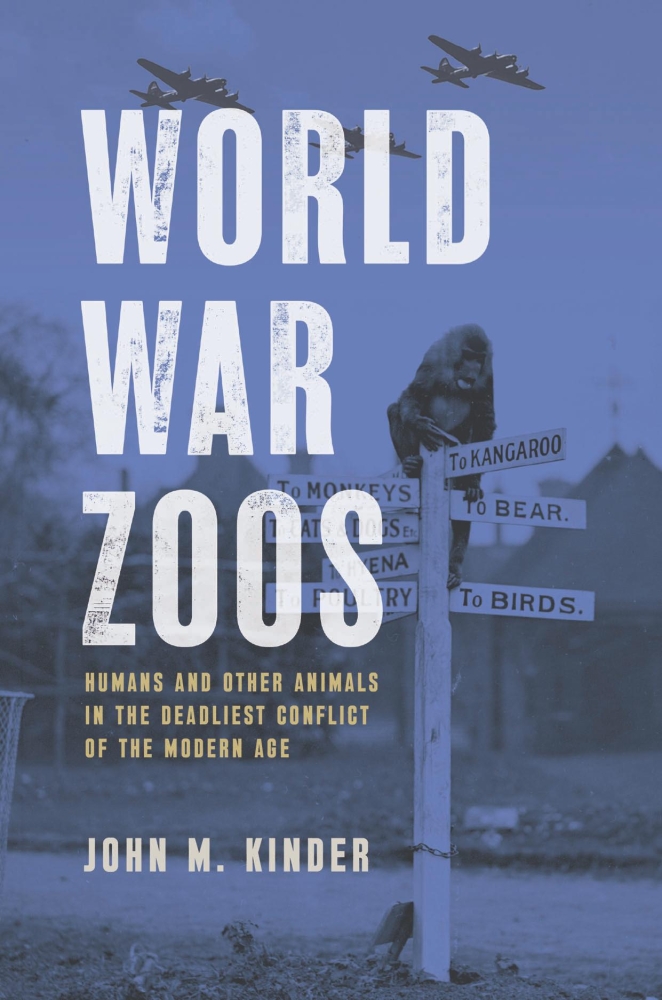

| Title: | World War Zoos - Humans and Other Animals in the Deadliest Conflict of the Modern Age |

| Writer: | Kinder, John M. |

| Published: | The University of Chicago Press |

| Published in: | 2025 |

| Pages: | 384 |

| ISBN: | 9780226827667 |

| Description: | John M. Kinder, Director of American Studies and professor of history at Oklahoma State University, describes in his book World War Zoos how zoos worldwide came through the years of war. According to him, World War Two was, “more than anything before or since […] an existential threat to the globe’s zoological institutions”. He mentions bombardments, foreign occupation and looting by hostile troops as examples thereof. However, farther away from the front and outside occupied areas, zoos faced immense problems, so the author shows in his book. Questions such as how to deal with dwindling stocks of food and which animals could be euthanized to spare others. And did zoos have a right to exist in wartime anyway? Kinder estimates that a total of 25,000 zoo animals in zoos didn't survive the war which stands in no relation to the 70 million human victims. Why it does make sense to pay attention to zoos in wartime is, according to Kinder, because zoos were a microcosmos of the cities they were located in. “The history of zoos during world War II reminds us that war’s traumas and upheavals weren’t confined to the battlefield. Bombed, looted, starved, occupied: not even the city zoo could escape the conflict unscathed.” In the words of the author, zoos form “a lens through which to explore the rise of Nazism, the moral dramas of collaboration and resistance, and the urge to rebuild in the wake of apocalyptic destruction”. On writing this book, the author has set himself three goals. Firstly, he wants to categorize the impact World War Two had on zoos and their animals worldwide. He figures out which problems management and caretakers faced and how these were solved. Secondly, Kinder wants to show how in zoos people looked at nature with a hierarchical view in which people were superior to animals and how some animals were rated higher than others. His third goal is the most important and deals with the research into the human-animal relations in a period of social trauma. The recurring question is how far the existence of a zoo is justified in a period in which millions of human lives are at stake. Kinder starts with describing the pre-war period in which zoos worldwide faced financial problems during the crisis of the 30s. Next he explains how the fate of the zoos in Madrid and Barcelona during the Spanish civil war were a preview of what awaited other zoos in Europe. In both Spanish cities, zoo animals were hit by bombs or died of starvation. When war broke out on September 1, 1939, the London Zoo closed down for the first time in a century (not mentioning Christmas) to reopen after about fourteen days. In that period, over 200 animals were euthanized by staff members, fearing they might escape during bombardments. Such preventive measures were taken elsewhere as well, for instance in Ouwehands Dierenpark on the Grebbeberg in Rhenen in the Netherlands. Prior to the Battle of the Grebbeberg, founder and director Cor Ouwehand shot the predators himself as he had little faith in the marksmanship of the Dutch troops. The fate of zoo animals, according to Kinder, depended on “their proximity to military targets, the whims of weather, the randomness of human decision-making and the chaos that would define urban war”. “The lines between ‘battlefield’ and ‘home front', disappeared worldwide,” the American writes, “zoos were simply in the way – collateral damage of a total war.” This gave birth to shocking stories such as that of a caretaker in Dresden Zoo who encountered injured and dead animals all over the zoo after the Allied bombing of the city in the night of February 13 to 14, 1945; among others a baby elephant lying in a dried up moat with a serious abdominal injury and a gibbon which had lost its hands and helplessly held up its bloody stumps. Apart from bombings, shortages of food were the largest threat to zoos. Importing exotic food was almost impossible for zoos worldwide: why would ship's crews put their lives on the line to import bananas for hungry monkeys? Alternatives had to be found: on various locations, fake bananas were made of sweet potatoes mixed with honey. In London Zoo, penguins were fed with strips of cats meat dipped in cod liver oil. Not only because the shortage of food, zoos in wartime had to deal with shortages of staff as well, as male caretakers were drafted into military service. In various zoos, this was compensated for by women taking over the work of the men. As to sense of duty, women turned out to be equal to men. A female caretaker of Belfast Zoo even went so far as to take her favorite baby elephant home with her at the end of her day shift because in her walled in garden, she could protect the animal better against nocturnal bombardments. An even greater danger to zoos than bombings and hunger was, so Kinder writes, irrelevance: in war societies, there is always doubt about the use of maintaining zoos because why can this form of entertainment still exist in times when each citizen is appealed to frugality and sacrifice for the fatherland. Therefore zoos pulled out all the stops to prove their value in wartime. They played their patriotic role to make war propaganda. One example is the panda bear Ming from London Zoo which, on both posters and other publications like news reels, posed as the symbol of British steadfastness. A helmet was put on its head, the Union Jack was pushed in its claws and the animal entertained members of the female division of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). .Zoos were able to support the war effort in other ways as well. The author mentions Philadelphia Zoo where snakes were milked in order to produce anti-venom to be used by American troops fighting in the Pacific where snake bites posed a mortal danger. During the war, a new audience visited the zoos: the military. Looking at animals kept them occupied and diverted them from the severe ordeals awaiting them or those they had endured. Kinder further shows that, apart from being locations where people could find some diversion from the horror, zoo sometimes were part of the evil as well. In Nazi-Germany, zoos were an inseparable part of the dictatorial regime. Kinder notes that not a single German zoo manager protested against Jews being denied entrance. In Artis Zoo in Amsterdam and the Warsaw Zoo on the other hand, Jews and others who wanted to escape from the Nazi regime were being helped by zoo management or staff. This way, Kinder shows that within the cadre of good and evil, zoos could take any side. Kinder finishes his compelling book with a conclusion in which he cleverly connects history to the present where climate change poses a new threat to the world and to the zoos. Those who are interested in the history of zoos and in man-animal relations can't ignore this informative and well-founded book. World War Zoos includes an extensive bibliography and various fine pictures and other illustrations to support the text. |

| Rating: |     Very good Very good |

Information

- Translated by:

- Arnold Palthe

- Article by:

- Kevin Prenger

- Published on:

- 27-07-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Images