Former Prison Hameln

The origins of Hameln Prison go back to the Stockhof, established in 1698. This early facility housed prisoners who had been sentenced to forced labor, particularly in the construction of fortifications. Its name derived from the practice of confining inmates in wooden stocks at night in their dormitories to prevent escape. Overcrowding soon became a problem, and in 1713 a new prison was constructed to accommodate the growing number of inmates.

By the early nineteenth century, the city of Hamelin had lost its military fortress, and in 1827 a new penitentiary was built on the former fortress site, directly on the banks of the Weser River. This complex included three wings and several outbuildings, some of which still survive. It was designated the Royal Penitentiary and, after the annexation of Hanover by Prussia in 1866, it became part of the Prussian prison system.

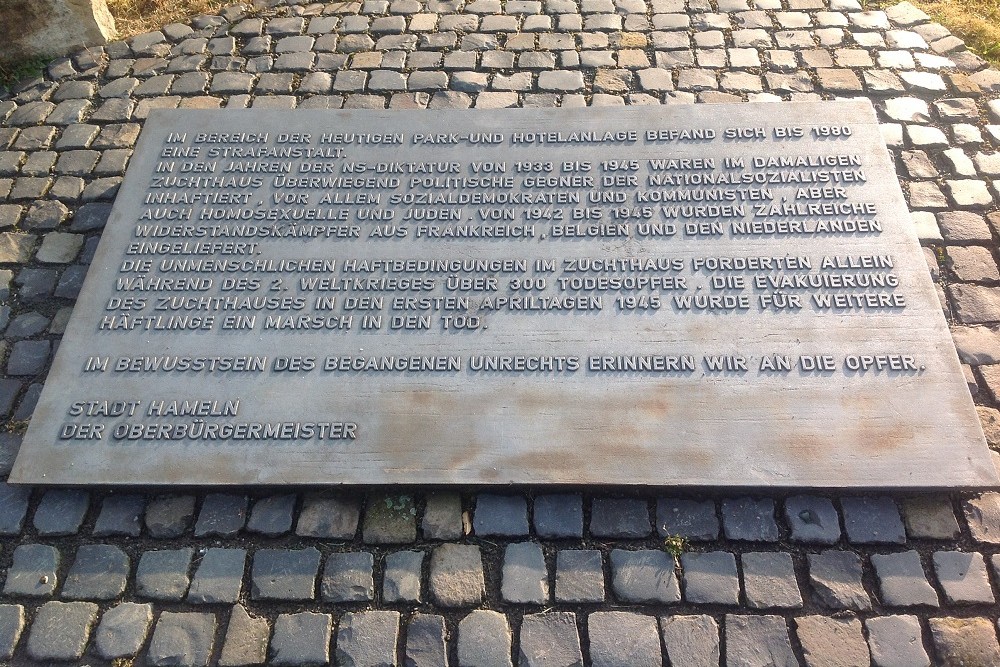

From 1933 onwards, Hameln Prison became a site of political repression. Alongside roughly 500 criminal prisoners, the Nazis incarcerated hundreds of political opponents, including communists, social democrats, trade unionists, homosexuals, and Jews. In 1935, the prison’s outer walls were raised and the institution was formally converted into a penitentiary.

During the Second World War, the prison population expanded to include foreign political prisoners, particularly from France and Denmark, many of whom were classified as “Nacht und Nebel” (Night and Fog) prisoners—individuals who were meant to disappear without trace. Conditions were harsh, and according to official statistics, 305 prisoners died between 1939 and 1945, including 55 who perished even after liberation by American troops due to illness and exhaustion.

On 5 April 1945, as Allied forces approached and Hamelin came under bombardment, the SS ordered the evacuation of the prison. Prisoners were forced on a march toward the Holzen satellite camp of Buchenwald, a grueling trek along the Ith ridge that became a death march for many.

After the war, Hameln Prison took on a new and grim role. From 13 December 1945 until 1949, it was used by the British military government as the principal execution site in their occupation zone. The executions were carried out by the British hangman Albert Pierrepoint, who became one of the most prolific executioners in modern history.

In total, 156 convicted war criminals were executed here. Among the most infamous were Josef Kramer, commandant of Bergen-Belsen; the camp doctor Fritz Klein; and female guards such as Irma Grese, Elisabeth Volkenrath, and Johanna Bormann, all convicted at the Bergen-Belsen Trial. Others executed included Ravensbrück guards Dorothea Binz, Ruth Neudeck, Elisabeth Marschall, and Emma Zimmer, as well as SS officers such as Bernhard Siebken, a battalion commander of the 12th SS Panzer Division, and Fritz Knöchlein, responsible for the massacre of British prisoners at Le Paradis in 1940.

In addition to war criminals, 44 other individuals were executed for crimes under Allied occupation law, including 42 former forced laborers, many from Eastern Europe, convicted of violent crimes in the chaotic postwar years. The final execution at Hameln took place on 6 December 1949, when Jerzy Andziak, a displaced Polish man, was hanged for a fatal shooting.

After executions, the bodies of those hanged were initially buried within the prison grounds. In 1954, under pressure from local groups, the remains of 91 executed Nazis were exhumed and reburied in Hameln’s Am Wehl Cemetery, where they were placed in individual graves. This reburial later became a point of controversy, as neo-Nazi groups attempted to use the site for commemoration well into the 1980s.

In 1955, Hameln Penitentiary was officially closed, and its remaining inmates were transferred to Celle Prison. On 1 October 1958, the site was repurposed as a youth correctional facility, which remained in operation until 1980, when a new youth prison was built in nearby Tündern.

With the closure of the correctional facility, the prison complex fell into disuse. In 1986, the central cell block and the east and west wings were demolished. However, several historic buildings were preserved. These were later restored and converted into a hotel, which opened in August 1993, ensuring that the site remained part of Hamelin’s urban fabric while also serving as a reminder of its layered and often grim history.

A Memorial plaque is located at front of the former prison.

Do you have more information about this location? Inform us!

Source

- Text: TracesofWar

- Photos: Bert Molkenboer

Related books

Nearby

Point of interest

Monument

- Commemorative panel Minster Church of Saint Boniface - Hameln

- Memorial Richard Klages - Hameln

- Bismarck-tower Hameln - Hameln

Cemetery

- Graves Victims Hamelner Zuchthaus - Hameln

- Dutch War Graves Hameln - Hameln

- Graves Forced Laborers & Soviet Prisoners of War - Hameln