African American Personnel in the US Navy

Segregation in the navy

The United States Navy was segregated, as was American society. For example, there were separate schools or cafes for African American citizens and white citizens. Up to 1920, African Americans were among other crew members accepted aboard Navy vessels, but since 1920 it was prohibited. Instead, special units came, that didn't exist long. From 1922 on, African Americans were excluded from the Navy. Instead, Philippine citizens were put to work to perform various small tasks on board. This situation didn't change until 1932, when the Philippine independence movements started to rise and new volunteers were needed. From that moment, African Americans could only be employed as stewards, which meant working in the kitchen. This implied cooking and serving food, doing the dishes and performing other simple duties.[1]

An African American is serving a meal as a steward at the officers mess aboard an American warship. Source: Naval History and Heritage Command

Kitchen staff

In June 1939, the US Navy numbered 2,807 African Americans, while the total number of Navy personnel stood at 125,202 men, so they made up 2,2% of the total. Not a single African American served as an officer or an adjutant. In June 1940, already 4,007 African Americans served in the Navy, but still no one had an officer rank. In June 1941 the number ran up to 5,026 men. That year the total number stood at 383,150 people. However, we don't know whether this count was made at the beginning or at the end of the year.[2]

On May 2, 1941, Afro Americans were excluded from jobs other than kitchen work by Frank Knox, Secretary of the Navy under President Franklin Roosevelt as, according to him, this would evoke disunity and demoralization. In October 1941, he would repeat that it would be better if African Americans were only incorporated in the kitchen staff, which would help the ship to function as a whole. Earlier he explained that African Americans were not allowed to fight along with other crew members, because letting "men of the colored race" work in the kitchen only would be "in the best interest of overall ship efficiency".[3] It was only on the 7th of April 1942, that Knox would hesitatingly admit that African American volunteers could be accepted for general service. .[4]Frank Knox died on the 28th of April 1944. He was succeeded by James Forestal, who was more sympathetic towards African American participation.

More African Americans serving in the Navy

In December 1942, President Roosevelt announced that volunteers were no longer accepted into the armed forces, instead the conscription was imposed. In February 1943, this also applied to the Navy. Henceforth, African Americans would make up 10% of the crew, which corresponded to the percentage of African Americans in the population. This decision was made in consideration of whites who were afraid, that a large number of African Americans would stay behind in the US while they were fighting themselves.[5] It would take until April 1944, before the first African American officers appeared in the Navy. In December 1943, there were 101,573 African Americans serving in the Navy; in June 1944 there were 142,306; in December 1944 their number had risen to 152,895, and just after the war, in October 1945, there were 165,466. In 1945, they formed 4,8% of the total number of men serving in the Navy which amounted to 3,405,525 men that year.[6]

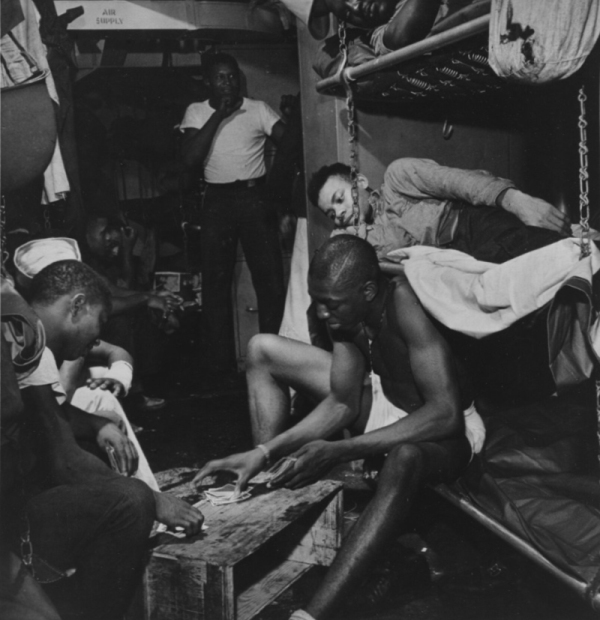

Afro-American stewards killing time aboard a U.S carrier off the coast of Manilla. November 1944. Source: Naval History and Heritage Command

Discrimination

African Americans had to endure continuous discrimination through their participation in the war. After munition exploded in Port Chicago in California, resulting in more than 300 casualties, most of them African American, 50 other African Americans were punished after they refused to continue their work that day. Almost all men who refused to keep working in Port Chicago and got detained, were not released until the 12th of January, 1946, after the Navy had taken steps to promote mixed units.

Racial tensions on Guam

On the island of Guam in the Philippine Sea, African Americans had to take up weapons in December 1944 to protect themselves against white attackers. The Japanese-held island was recaptured by the Americans on the 10th of August 1944. At Christmas 1944, the situation in Agana, the largest city on the island, escalated. Americans went to the city for entertainment and relaxation. Both white Marines from the Third Marine Division and African Americans on leave made contact with the local female residents, which the first group did not appreciate from the second group. Local initiatives, mostly taken by small groups, arose to keep African Americans away by throwing them out of the city or by pelting them with stones or smoke grenades. The provost-marshal tried to de-escalate the situation by emphasizing that discrimination was forbidden; in the meantime the complaints of the African Americans were not taken seriously.[7]

On Christmas Eve, the tension increased between the white Marines and the African Americans. The white Marines were shooting at the African Americans to chase them away from the city. The African Americans wanted to go back, when they were told that one of their friends was shot down. The military police and the return of the missing friend resulted in a peaceful outcome. However, it almost led to confrontation again later, when the Marines came to get revenge for one of their comrades, who was wounded when a piece of coral was thrown against his head.

During the day situation escalated again. An African American was shot down by drunken Marines. Among other rumors circulating was one telling that an African American had killed a white man, and one about an African American who was injured after a shooting. Situation escalated even further when the African American camp was strafed from a jeep by a machine gun. The African Americans hit back, but the perpetrators were able to escape. A white military police man was wounded when he was shot at by African Americans who were out for revenge. More than 40 of them climbed into a truck to claim their rights with clubs and knives in Agana. They were stopped at a roadblock and then arrested and later imprisoned. Also some of the white men received punishment for taking part in the confrontation.[8]

The end of segregation

The first results in relaxation of segregation became visible only in the end of the war. For example, there was a destroyer USS Mason, which had 160 African Americans and 44 whites on board. Another example was the submarine hunter PC 1264, which had 53 African Americans on board and eight whites.[9] The gradual relaxation of segregation was not necessarily motivated by idealistic reasons. A disadvantage of segregation was, for example, that training camps had to be available twice. Also, separate facilities had to be set up for African American recruits. Only after World War Two segregation finally came to an end.

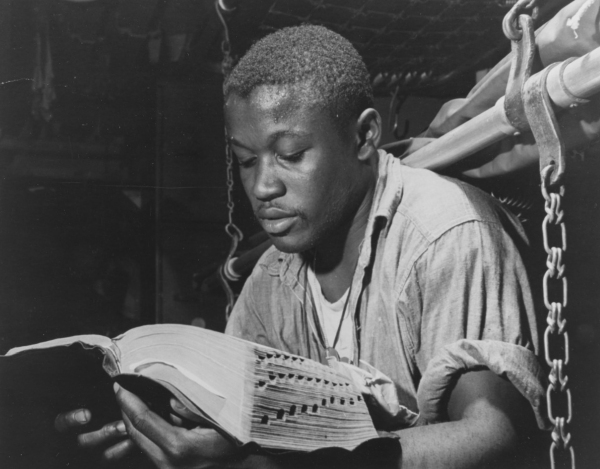

Stewards Mate Second Class James Lee Frazer is reading the Bible aboard a U.S. aircraft carrier off the coast of Manilla. January 9, 1945. Source: Naval History and Heritage Command

Notes

- L. D. Reddick, ‘The Negro in the United States Navy during world war II’, The journal of negro history 32.2 (1947) 203.

- Naval History and Heritage Command, ‘U.S. Navy Personnel Strength, 1775 to Present’ (2 augustus 2016), www.history.navy.mil (22 november 2018); Reddick, ‘The Negro in the United States Navy during world war II’, 211.

- William R. Mueller, ‘The Negro in the Navy’, Social Forces 24.1 (oktober 1945) 112.

- Reddick, ‘The Negro in the United States Navy during world war II’, 207-208.

- Reddick, ‘The Negro in the United States Navy during world war II’, 210.

- Naval History and Heritage Command, ‘U.S. Navy Personnel Strength, 1775 to Present’ (2 augustus 2016), www.history.navy.mil (22 november 2018); Reddick, ‘The Negro in the United States Navy during world war II’, 211.

- Kevin Prenger, Kerstmis onder vuur. Kerst tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog: aan het front, thuis en in de kampen (z.p., 2018) 228-229.

- Prenger, Kerstmis onder vuur,’ 228-229.

- Mueller, ‘The Negro in the Navy’, 115; Reddick, ‘The Negro in the United States Navy during world war II’, 214, 216.

Definitielijst

- marshal

- Highest military rank, Army commander.

Information

- Article by:

- Samuel de Korte

- Translated by:

- Liza de Groot

- Published on:

- 30-03-2019

- Last edit on:

- 15-06-2020

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Sources

- Mueller, William R., "The Negro in the Navy", Social Forces 24.1 (October 1945) 110-115

- Naval History and Heritage Command, "U.S. Navy Personnel Strength, 1775 to Present" (the 2nd of August 2016) www.history.Navy.mil

- Reddick, L. D., "The Negro in the United States Navy during world war II", The journal of negro history 32.2 (1947) 201-219