The War at Sea

By Francis E. McMurtrie

The War Illustrated, Volume 8, No. 193, Page 390, November 10, 1944.

In the Far East the pace of the war is increasing. The First Lord of the Admiralty has stated that "a fleet capable in itself of fighting a general action with the Japanese Navy" is being transferred to the Pacific. It will include an immense train of auxiliaries of every kind, from escort aircraft carriers down to landing craft, the need for which will be great owing to the immense distance from Allied bases at which actions are likely to be fought.

With the American landing in the island of Leyte, October 20, 1944, the campaign for the reconquest of the Philippines has opened.

In attempting to expel the attackers by a naval offensive, the Japanese have made their situation infinitely worse. While their fleet still existed as an intact unit it was bound to exercise a certain constraint on Allied movements at sea; but now it has suffered a severe defeat in the Philippines battle, with the loss of certain of its more important units and the crippling of many others, there is little to prevent the Allied Navies from ranging far and wide, interrupting the vital communications on which depend not only the maintenance of Japanese armies abroad but the sustenance of the population at home.

A fatal mistake was made when the authorities in Tokyo assumed the truth of the claims made by their aircraft to have sunk or damaged a dozen Allied aircraft carriers and various other ships. Relying on this information, they took the risk of sending all their available fighting ships into the waters of the Philippines. No better opportunity could have been wished for by the Allied naval commanders. At the cost of one aircraft carrier of moderate size, the U.S.S. Princeton, two escort carriers, two destroyers and a destroyer escort, losses of a much more serious character were inflicted on the enemy. At the time of writing, these are understood to comprise four aircraft carriers, two battleships, six heavy and three light cruisers and six destroyers. Nearly all the more important Japanese ships were badly mauled, and their repair will take time in the present congested state of enemy shipyards.

H.M.A.S. Australia, wearing the pennant of Commodore J. A. Collins, R.A.N., in command of the Australian squadron operating with the U.S. Pacific Fleet, received a bomb hit on or near the bridge, killing 19 officers and men and wounding 54, including the Commodore himself. Otherwise, no extensive damage is reported by Admiral Halsey, who commands the Allied naval forces in the Philippines and is entitled to the chief credit for this important victory.

In the early days of the war it was possible to ascribe the erratic strategy of the Japanese Navy to the fact that it was dominated by the Army under General Tojo. Now that Admiral Yonai has been given a freer hand under the present regime, it might have been expected that such a miscalculation as that which precipitated the Battle of the Philippines would have been avoided. It would seem, indeed, that as the war progresses our Eastern foes are showing increasing signs of being "rattled".

Superior Strategy Caught the Japanese Napping

It is probably that the enemy were by no means certain where the blow was going to fall, and were thus taken entirely by surprise at Leyte. It is said that preparations had been made to resist an invasion of Mindanao, the great island immediately to the south. Possibly also an attack on Formosa or the Ryukyus was feared. In Far Eastern countries enormous importance is always attached to "saving face", or in other words, avoiding the loss of prestige. To the people of Japan, the loss of the Philippines would not mean much in this way; and to lose Formosa even would be regarded as a minor blow. Thus it seems likely that what is left of the Japanese fleet will not be husbanded as much as possible, so that it may ultimately fight under the most advantageous conditions, close to its home shores when those are threatened.

There is still a very limited amount of information about the Japanese Navy and its present strength. After its latest losses it may include eight battleships, three of which are new units of 45,000 tons, armed with 16-in. guns. Aircraft carriers may number nine or ten, few of which are first-class vessels. Cruisers have been variously estimated, according to the assessment of losses, but a maximum figure would be about 30. Destroyers, in spite of heavy casualties, may be as many as 80, and submarines are quite as numerous.

The United States Navy should be able to dispose of twice as many ships in each of the foregoing categories without exhausting its reserves. This superiority continues steadily to increase, as American shipyards have an infinitely greater capacity than those of Japan, and also build more rapidly. This does not take into account the very substantial force comprised in the British Eastern Fleet.

There is no doubt the Japanese Navy has been heavily handicapped owing to its strategy having been controlled by military men. The Naval Staff in Tokyo would probably have accomplished much more with the material at its disposal had it not thus been fettered. Audacious as the initial attack on Pearl Harbour may have been, it was deprived of any lasting effect by the enemy's failure to follow it up at once with a large-scale invasion of the Hawaiian group. Ultimately this seems to have been grasped, for the Battle of Midway nipped in the bud an enterprise which appears to have Hawaii as its objective. Incidentally, this action, owing to the heavy loss in aircraft carriers sustained by the enemy, proved the turning point of the whole war in the Pacific.

In the Solomons campaign the same halting strategy can be seen. Instead of overwhelming the Allies at the start by a concentration of the utmost force, the Japanese poured in reinforcements, with sea and air support, in small packets, which always just failed to turn the scale. In the end everything was lost as a result. Much the same process may be expected to follow elsewhere; Burma is an instance. There, sea communication between Rangoon and Singapore is practically non-existent as the outcome of British submarine operations.

British sea and air attacks on Sabang, Surabaya, the Andamans and the Nicobars, have given the enemy warning that his hold on Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies is growing more precarious. In the near future the Japanese garrison in Singapore may find itself in much the same unenviable position as the Russians in Port Arthur in 1904.

Previous and next article from The War at Sea

The War at Sea

Finnish insistence on fighting to the last ditch for the benefit of Germany must inevitably affect the naval situation in the Baltic. Already the enemy, in accordance with the pact made by Ribbentrop

The War at Sea

Although U-boats are far from being extinct, there being still some hundreds in service, their area of operations has been greatly reduced. There appear to be none left in the Mediterranean, and they

Index

Previous article

I Was There! - It Was a 'Tough Do' at the Bridge of Arnhem

A handful of British parachute troops who fought on for three days and nights when surrounded at the end of the Arnhem bridge were taken prisoner, removed to Germany, then escaped to our lines. One of

Next article

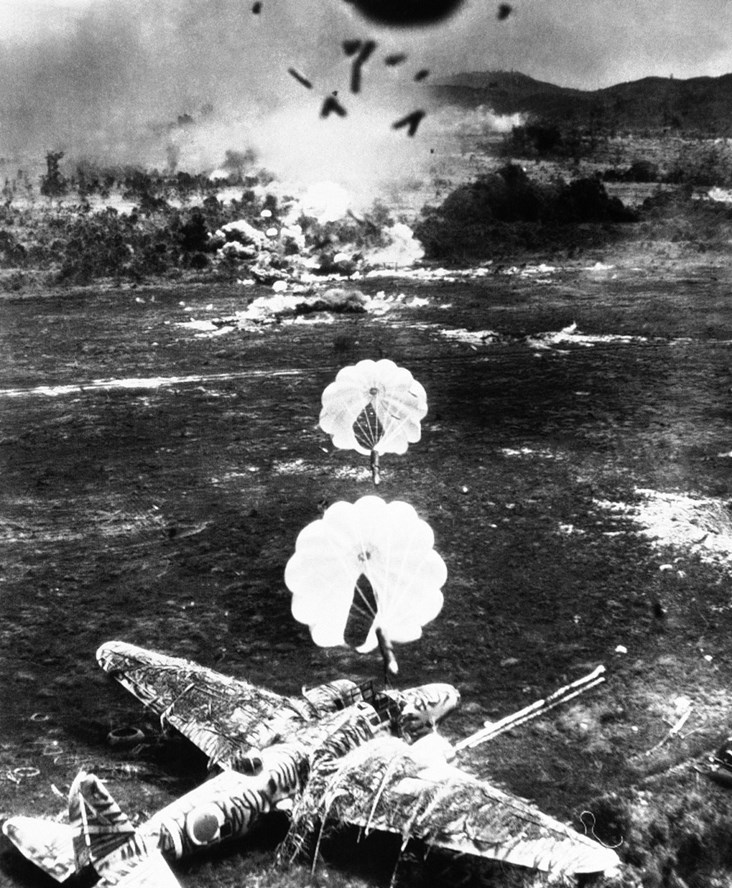

Parachute-Borne Fragmentation Bombs in Action

Terrific Damage was Wrought, on Japanese airfields by U.S. Army Air Forces during a raid on Buru Island, near Celebes, in the battle for New Guinea in July 1944. A few seconds after this photograph