Memorial HMS Bulwark and HMS Princess Irene

This memorial, on Woodlands Road Cemetery, commemorates the sinking of the HMS Bulwark and HMS Princess Irene.

HMS Bulwark exploded on 26 November 1914. Out of her complement of 750, no officers and only 12 sailors survived.

HMS Princess Irene exploded on 27 May 1915. A total of 352 people were killed.

-----------------------------------------

HMS Bulwark was part of the 5th Battle Squadron and at the outbreak of the war was based at Sheerness in order to protect the South East of England from the threat of a German invasion.

On Thursday 26 November 1914, she was moored in the Medway Estuary approximately between East Hoo Creek and Stoke Creek when, at 7.50am a massive explosion ripped through the vessel. The Times reported

"The band was playing and some of the men were drilling on deck when the explosion occurred. A great sheet of flame and quantities of debris shot upwards, and the huge bulk of the vessel lifted and sank, shattered, torn, and twisted, with officers and men aboard..."

Boats of all kinds were launched from the nearby ships and shore to pick up survivors and the dead. Work was hampered by the amount of debris which included hammocks, furniture, boxes and hundreds of mutilated bodies. Fragments of personal items showered down in the streets of Sheerness. Initially 14 men survived the disaster, but some died later from their injuries. One of the survivors, an able seaman, had a miraculous escape. He said he was on the deck of the Bulwark when the explosion occurred. He was blown into the air, fell clear of the debris and managed to swim to wreckage and keep himself afloat until he was rescued. His injuries were slight.

The CWGC database names 788 men from HMS Bulwark as having lost their lives in this explosion. There was only a handful of survivors.

---------------------------------------------

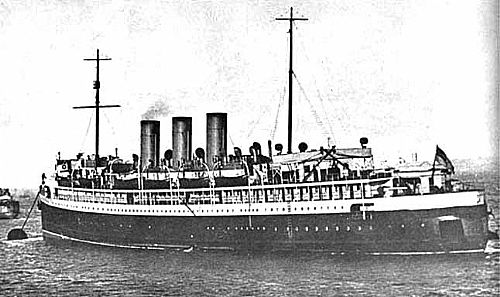

In May 1913 the Canadian Pacific Railway had placed an order with Denny’s of Dumbarton for two new ships for their route on the Pacific coast between Vancouver, Victoria and Seattle. The ships were elegant and well appointed three-funnelled vessels 350 feet long with a 54 foot beam and displacing 5,500 tons. Oil-fuelled boilers drove two propellers via steam turbines to give a maximum speed of over 23 knots.

The first of the ships, the Princess Margaret, was launched on the 24 June 1914 and, following fitting out and completion of sea trials, she was ready for delivery on 15 November. The owners had planned to sail her round Cape Horn to Vancouver, however, there were concerns about German warships in the Southern Ocean; the Battle of Coronel having been fought two weeks earlier. Consequently, the delivery voyage was postponed.

Her sister ship the Princess Irene was launched on 20 October 1914 and there was talk of the Princess Margaret awaiting her completion before they sailed to Vancouver together.

The Royal Navy was meanwhile coming to terms with a relatively new facet of warfare – mines. As the war progressed, they first laid defensive minefields off Britain’s coast to try and deter German raiders from bombarding coastal towns, and then they looked at laying offensive minefields off the coast of Europe to help enforce the blockade on Germany. They realised that if they had fast mine-laying ships they could cross the North Sea at high speed late in the day, lay their mines unseen at night, and be heading back to friendly waters before daylight.

Consequently, they looked for suitable vessels and the two Canadian princesses were amongst those requisitioned. They were stripped of all their fittings such as wooden panelling, before stowage for more than 400 mines, the mine launching rails and defensive guns were installed. The Princess Irene was delivered to the Royal Navy on 26 January 1915 and after conversion left the Clyde for her new base at Sheerness, Kent, on 18 March.

Under the command of Captain Mervyn Cobbe, and with a crew of 225 officers and ratings, she carried out her first operation in late April when she laid 280 mines in the English Channel. In early May she then carried out a second operation laying mines north-west of Heligoland, before returning safely to Sheerness.

On 25 May the Princess Irene was moved from moorings near Sheerness Dockyard to a quiet anchorage in Saltpan Reach, in preparation for another operation. A new load of mines was ferried out to her in barges, with loading starting on the morning of the 26th when each of the mines was lifted aboard and stowed on the rails.

Once all the mines were loaded and secured the task of priming them was begun. To do this a cover plate was removed and the detonator and primer were fitted. At the time the navy used the Heneage pistol that required the striker pin to be ‘cocked’ by a compression spring before inserting into the mine. There were inherent dangers with this type of pistol and so the task of cocking and fitting them should only have been entrusted to well-trained and experienced men. The navy, knowing of problems with this type of pistol, was at the time in the process of introducing an improved design.

The morning of 27 May 1915 saw a hive of activity on and around the Princess Irene. At about 7 a.m. a party of Sheerness Dockyard workers arrived, as they had been doing for the previous three weeks, to complete work on increasing the Princess Irene’s mine carrying capacity and strengthening her decks. Also on board were 89 men from Chatham Dockyard to help with priming the mines.

At about 9.15 a.m. three of the Princess Irene’s crew went ashore, one was the ship’s postman going to collect the mail, and another was probably not really looking forward to a visit to the dentist! At 11.10 a.m. Mr Quint, who was in charge of the refit work, left the Princess Irene with five men who had been onboard removing slings for testing ashore.

Four minutes later disaster struck. The Princess Irene was enveloped by an enormous explosion, likened by one witness to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Where a few seconds earlier an elegant new ship had been bobbing peacefully at her moorings, there was now just a column of flames, smoke and debris rising high into the sky. Another witness described how the Princess Irene seemed to be hurled into the air a mile high in 10,000 fragments, and how he could make out the forms of men amidst the flying wreckage.

The buildings in Sheerness three miles away shook in the blast wave, and debris rained from the sky. On the Isle of Grain four of the navy’s oil storage tanks were ruptured and the pumping station and main pipeline damaged by pieces of the ship’s side falling on them.

In Grain village, nine year-old Hilda Johnson was killed in her uncle’s garden when she was stuck by a piece of wreckage, and in the fields nearby 47 year-old farm labourer George Bradley dropped dead from the shock. Others onboard nearby ships were injured and on a coaling ship, about half a mile from the Princess Irene, a large piece of steel plate killed a crewman, two others were injured and a deck crane was toppled by a section of ship’s boiler falling onto the deck.

Debris landed for miles around and lighter objects were reported as being found at Detling, 11 miles away. The police had to ask residents in a wide area to conduct searches of their properties for debris and human remains, while farm workers were enlisted to search the local orchards and fields for body parts.

The explosion killed more than 380 men on board. All of the Princess Irene’s crew except for the three men ashore perished; all the Sheerness Dockyard workers, except Mr Quint and the five men who had just left the ship died. All the Chatham Dockyard workers were also killed except for one extremely lucky man, Stoker David Wills, who was going for an early lunch in the forward galley at the time of the explosion. He was spotted struggling in the water amongst the oil and wreckage and rescued by the crew of a nearby tug. He suffered severe burns to his face, arms and hands but, after a long convalescence, was passed fit to resume service and remained in the Navy for a further 12 years. He named one of his daughters Irene after the ill-fated ship.

Do you have more information about this location? Inform us!

Source

- Text: Fedor de Vries/Western Front Association

- Photos: Anthony (Sharky) Ward (1, 2), Anthony (Sharky) Ward (3), Anthony (Sharky) Ward (4)

- https://www.westernfrontassociation.com/world-war-i-articles/the-loss-of-hms-bulwark-26-november-1914/

- https://www.westernfrontassociation.com/world-war-i-articles/death-of-a-princess-the-destruction-of-hms-princess-irene-27-may-1915/

Nearby

Museum

- Royal Engineers Museum and Library - Gillingham

- Fort Amherst - Gillingham

- Historic Dockyard Chatham - Chatham

Point of interest

- Air-Raid Shelter Brompton - Brompton

- Air-Raid Shelter Restoration House - Rochester

- Soviet Foxtrot Class Submarine - Rochester

Monument

- Memorial HMS Glatton - Gillingham

- Memorial Chatham 'Drill Shed' Air Raid 3 September 1917 - Gillingham

- Remembrance Tree Cpl Andrew George McIlvenny RE - Gillingham

Cemetery

- Dutch War Graves Woodland Cemetery Gillingham - Gillingham

- Commonwealth War Graves Woodlands Cemetery - Gillingham

- Graves of VC Recipients Gillingham - Gillingham