Introduction

The story of the Line-crossers cannot be told without first dwelling on the history of the area in which they operated and the organizations to which they belonged.

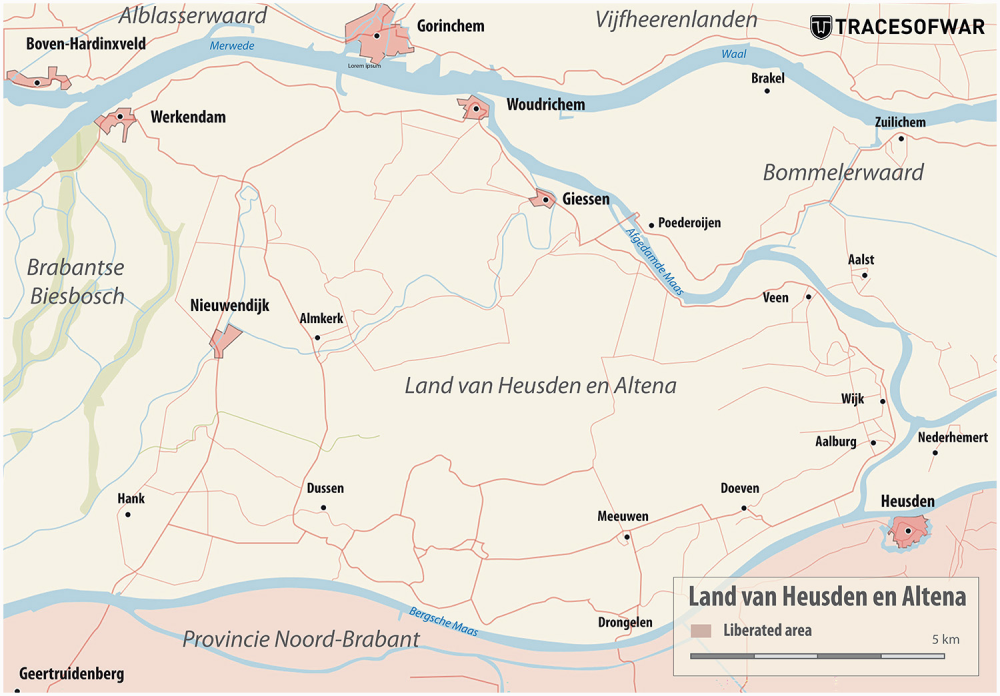

After the liberation of the southern part of the Netherlands by the Allies in late Autumn of 1944, the Biesbosch area formed a kind of no man's land between liberated and occupied territory. There was some German military presence but only in strategic or accessible places.

Between November 1944 and May 5, 1945, the day when the German armed forces in the Netherlands capitulated, this area was the scene of hundreds of crossings in rowing boats and canoes right across the front line, from occupied to liberated territory and back again. These crossings, mainly from the towns of Sliedrecht and Werkendam, served to transfer intelligence and/or people.

In his magnum opus ‘The Kingdom of the Netherlands during World War II’, the historian Dr L. de Jong devotes only a few pages to these events. Yet, these crossings were of great importance for the Allied war effort. And equally important, it provided the Dutch government-in-exile in London and the Military Administration in the liberated southern Netherlands a good view of the situation in the northern part of the country that was still occupied.

What had started in November 1944 as an opportunity to transport intelligence obtained by espionage through the Biesbosch to liberated territory developed into a regular, almost daily connection in subsequent months. Apart from intelligence, people were transported as well. These were mainly stranded Allied soldiers on their way to liberated territory but also couriers and others whose arrival in the liberated South was wanted.

From February 1945 onwards, large quantities of medicines that were no longer available in occupied Netherlands were taken on the return journey, in addition to weapons, passengers and messages. The medicines mainly involved insulin, which saved many lives

After a while, most crossers started operating mainly from liberated territory.

The best-known crossers were those of the Albrecht Group, which collected military intelligence in occupied territory. They carried out a total of about 367 crossings under the direction of the Dutch military intelligence service (the ‘Bureau Inlichtingen’). There were also non-aligned crossers, called ‘Wild Crossers’. They acted on their own initiative and often had links to the resistance in towns along the Merwede River and in the Alblasserwaard polder. These Wild Crossers were a mixed bunch; some were relatively professional, whereas others were adventurers who only wanted to go to liberated territory.

Definitielijst

- Bureau Inlichtingen

- Set up in November 1942 in London by the Dutch government in exile after the completely botched agent droppings in occupied Netherlands (the ‘Englandspiel’). This new service cooperated with MI6 and was very successful

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

The Biesbosch during the war

The Biesbosch (‘Bullrush Forest’) area is a large freshwater tidal area, located some 25 kilometres southeast from the port of Rotterdam. The area’s unique character is the result of a huge destructive flood in the early part of the 15th century that carved up the land into a dense maze of small creeks and waterways, full of reed beds and willow forests, making it difficult to access.

Over the centuries, the supply of river silt created new pieces of land and parts of the Biesbosch were reclaimed. This was fertile land suitable for agriculture and cattle breeding and, logically, a number of farmers settled there whose farms were only accessible by water. Nevertheless, apart from the major waterways, for those who did not know their way around, it was still a difficult area to access during the occupation period. Apart from farmers, the Biesbosch had also been the working area of wicker workers for centuries. They cut reeds, rushes, and cut and sold the brushwood for use in hydraulic engineering projects, among others.

Also, in those days the difference between ebb and flood was as much as 2 metres, causing the Biesbosch to fill up and empty again every 12 hours or so. In present times, these tidal differences have become much smaller as a result of the completion of the post-war Delta Works [ the largest engineering project in the Netherlands, undertaken in the late 1950s to late 1990s. It effectively reduced and strengthened the coastline to protect the southwestern part of the country from devastating storm surges, such as the flood disaster in February 1953 that killed over 1,800 people].

During the war, the Biesbosch soon became a place of refuge for people in hiding, who were relatively safe there. The Germans, and later the Landwacht, usually did not venture far into the area, and there were plenty of places to hide further away when disaster loomed on the horizon. These people in hiding found shelter and work with the local farmers but also stayed on houseboats and in the small wicker workers' houses that could be found here and there in the Biesbosch. Apart from people, the Biesbosch was also a good place to hide a number of river barges whose skippers had resisted the German requisition effort. The number of people in hiding in the Biesbosch is said to have been around 300 at the end of 1943.

Apart from Jews, men who evaded the Arbeitseinsatz and Allied pilots, those in hiding in the Biesbosch included resistance fighters who needed to stay out of enemy sight for a short time, or longer.

Out of this, the ‘Commandogroup Biesbosch’ or ‘Biesbosch Group’ (called ‘partisans’ by the Germans) emerged in the summer of 1944, raiding retreating or deserted German soldiers, disarming and imprisoning them in a few hidden houseboats and river barges. After September 5, 1944, also known as ‘Mad Tuesday’, many German soldiers who believed the Allies were approaching fast from the south moved through the Biesbosch alone or in small groups. They first let themselves be ferried across the Amer River from Drimmelen and then continued on foot through the polders and along the dykes in an attempt to reach the towns of Dordrecht or Werkendam.

With the help of the ferryman from Drimmelen, who warned of the approaching new ‘targets’ by hoisting a basket, the first Germans were ambushed and captured at the small bridge of Sint Jan around September 10, 1944. The first were imprisoned in a small houseboat, called the Grey Ark. When that boat became too cramped to accommodate the increasing number of captured Germans, they were imprisoned in the river barge ‘Martha Jacoba’. Later, the barge ‘The 8 Brothers’ was added to the make-shift prisons. The ships were hidden among the reeds in creeks near the ‘het Ganzennest’ (the Goose Nest) polder.

The small bridge of Sint-Jan as it can still be found in the Biesbosch. The text on the plaque reads: “1943-1945 Little bridge of Sint-Jan, symbol of resistance by the people in hiding, their helpers and line-crossers. Location where 75 enemy soldiers were disarmed by Biesbosch-commandos.” Source: Jan de Jager

In the course of time, this group which included some stranded Allied pilots, made 75 prisoners who had been apprehended at Sint Jan's bridge or elsewhere in the Biesbosch. During these raids, some were killed or injured. While most of these were Germans, the resistance also suffered a fatality. On September 23, 1944, Chris Hollebrands was shot in the head while waiting for some SS troopers. He died on the spot. The group received help from local doctors for the treatment of wounds and other ailments.

These prisoners comprised not only of Germans, but almost all nationalities conscripted by Nazi Germany. Amongst the prisoners, there were SS soldiers that caused unsustainable unrest in the boats. It was decided to execute them after holding a tribunal. These would have been five or six men, who were buried on the spot.

On October 8, 1944, a German officer escaped and miraculously managed to reach the small river town of Werkendam and informed his superiors about the partisans and their boats carrying German prisoners. Needless to say, this caused great unrest within the group and there were feverish discussions about what to do. Plans were made to gas the remaining prisoners or drown them by sinking the boats. These plans were not carried out. Many of these men had Christian backgrounds and killing so many people was something they could not reconcile with their faith or conscience. When this event was brought up years later in an interview with Piet van den Hoek, he still expressed his relief that these plans were not carried out. Another reason for abandoning the assassination plan was the fear of serious reprisals. So, it was decided to wait and see. The Germans did indeed take action. However, the German column en route to the Biesbosch from Dordrecht was spotted by British Spitfires and bombed on the Moerdijk bridge. The column turned back and thereafter no further attempts were made to penetrate deep into the Biesbosch.

Just in time, when the situation on the boats was slowly becoming untenable, the small village of Drimmelen was liberated. In the night of 5 to 6 November 1944, the two river barges sailed to Drimmelen where the 75 prisoners (and one woman who had been captured together with her German boyfriend) were handed over to the Polish army after a risky journey.

After this, the crossings began and the entire Biesbosch was declared a barred territory and finally, in January 1945, largely cleared by the Germans. In short, anyone who was in the Biesbosch during that period had no business being there according to the Germans and was therefore by definition suspect.

In the final weeks of the war, an Allied military operation took place in the Biesbosch called ‘Operation Bograt’. There were rumours circulating that the Germans were in the process of withdrawing from the Biesbosch. Captain André (Jos van Vijlen, more about him later) then came up with the plan to march with 40 resistance fighters through the Biesbosch to support the local resistance in Werkendam. For the weapons required, he sought help from Major Wall, of 48 RMC (Royal Marine Commandos) stationed between Willemstad and Geertruidenberg. However, Wall’s superiors found the plan insufficiently substantiated, but 48 RMC itself decided to send a few large combat patrols across the Bergse Maas River and the Amer River with the help of a few Belgian units, with the aim of liberating a number of villages. In preparation for this plan, a reconnaissance patrol consisting of eleven marines from X Troop of 48 RMC entered the Biesbosch in a few boats during the night of 20 to 21 April 1945 with the following mission:

- Investigate whether the buildings in the Steenen Muur polder were still occupied

- If so, the task was to try to capture the Germans present there for interrogation and then withdraw.

- If not, a small part of the patrol had to stay behind to check whether any Germans returned before the next morning. They would then also withdraw.

The Steenen Muur polder was indeed deserted, but when the patrol decided to withdraw, the boats were not at the rendezvous point. Because a radio had been damaged, it was no longer possible to contact the patrol and they were forced to remain there for the time being. In the meantime, a few Germans had turned up and were captured after a firefight. The boats had not yet turned up after a night on the Steenen Muur and the patrol decided to split up. Eventually, three marines decided to try to return to headquarters in Geertruidenberg by foot and swimming.

In the meantime, it had already been decided to start the operation anyway and the marines entered the Biesbosch in two LCAs (Landing Craft Assault) with the aim of capturing the small village of Hank, among others. One LCA hit a sunken ship in the port of Geertruidenberg and was in danger of sinking itself. It was soon discovered there were many mines all over the attack area and there was also fire contact with a German patrol. In the meantime, no contact had been made with the missing patrol and the attack was partly converted into a rescue operation.

The starting point of the operation was reformulated as follows on the morning of 22 April:

- Finding Major Wall's patrol

- Determining whether the Germans had withdrawn from the Biesbosch

The entire 48 RMC was deployed for this. The missing patrol was found in the Steenen Muur polder. The three other men were found on the Pauluszand and thus Operation Bograt ended. They did not want to risk any more unnecessary losses so close to the end of the war and on April 22, Montgomery announced a ban on attacks on the western Netherlands thereby hoping that the Germans would agree to food aid for the starving population.

The balance of the operation consisted of four Germans killed, four wounded and eight prisoners of war. 48 RMC itself suffered no losses. The sad downside was that the Germans had panicked as a result of the Allied actions in the Biesbosch and blew up a few more mills and church towers in a polder region, called Land van Heusden en Altena.

Definitielijst

- Arbeitseinsatz

- “Labour deployment”. Forced deployment in the German industry. Approximately 11 million European citizens were rounded up and deployed into forced labour in the Third Reich. Not to be confused with the Arbeidsdienst or labour service, an organisation for national-socialist education for Dutch youngsters.

- Jews

- Middle Eastern people with own religion that lived in Palestine. They distinguished themselves by their strong monotheism and the strict observance of the Law and tradition. During World War 2 the Jewish people were ruthlessly persecuted and annihilated by the German Nazis. . An estimated 6,000,000 Jews were exterminated.

- Landwacht

- Armed NSB-members with police authority.

- Nazi

- Abbreviation of a national socialist.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

The Albrecht Group

The story of the Line-crossers is inextricably linked to that of the Albrecht Group. This espionage group was founded in March 1943 by the former army officer H.G. (Henk) de Jonge, codenamed Albrecht, who himself called it Holland’s Glory. De Jonge, a deeply religious man whose faith played a major role in all his decisions, escaped from occupied Holland in July 1942. After a long journey via France, Spain, Portugal, Curaçao and New York, he managed to reach England in November of that year. There he was recruited by the Bureau Inlichtingen and trained as a secret agent. On March 12, 1943, he was dropped above the province of Drenthe in the Northeast of the Netherlands with the assignment of setting up a military and economic espionage network.

In doing so, De Jonge preferred to surround himself with like-minded people he knew and, above all, ex-military. Apart from him and his second in command Jo van Arkel (Jo), the leadership of the organisation initially consisted of Theo van Lier (Theo) and Cees van den Heuvel (Victor). Eventually, the ‘Albrecht’ group grew into a decentralised organisation of some 800 men and women who were subdivided into approximately 20 groups who knew little or nothing about each other.

Initially, getting the gathered intelligence to England was difficult. Unlike the usual short-wave transmitters, De Jonge received a telephone transmitter from England. With this transmitter contact could be made with aircraft or English ships off the Dutch coast, but it did not function well. Jo van Arkel tried to make contact from the Haarlemmermeer polder from where Van Arkel could hear the other side, but they could not hear him. His attempts to make contact from other locations in the large cities of The Hague and Leiden also failed.

Because contact with England remained difficult, Henk de Jonge decided to personally bring the collective intelligence work in the form of negatives to England via France. This attempt failed. He was arrested on September 1, 1943, when trying to cross the Pyrenees mountains into Spain, handed over to the Gestapo and later intensively interrogated in the Netherlands.

The other members of the group did not learn of his arrest until December 1943. In the meantime, his second in command, Jo van Arkel, had also been arrested. He and De Jonge appeared before the German Navy Court in the Netherlands (Gericht des Marinebefehlshabers in den Niederlanden) in Utrecht in July 1944 and were sentenced to death after a short trial. However, the sentences were not executed for unknown reasons. Instead they were transported to Germany where they were held captive in a number of German prisons and camps, which both barely survived.

On April 26, 1944, Jo van Arkel's successor, Theo van Lier, also tried to bring the microfilms to England. This attempt also failed because the boat on which they had left the city of Dordrecht encountered engine problems and drifted back to the coast. Van Lier and the four other passengers on the boat fell into the hands of the Germans. Two of them did not survive their captivity.

Van Lier was succeeded by Cornelis ‘Kees’ Brouwer from Dordrecht, who led the group until the end of the war by successfully managing to stay out of the hands of the Germans.

Even though many members were arrested, the group managed to build a nationwide, well-functioning espionage network in the course of 1944 and successfully kept several radio transmitters on air. Throughout its existence, the group exploited all opportunities that arose while displaying the necessary flexibility as demanded by the challenging circumstances.

The results of the espionage efforts were sent to the group's headquarters in Rotterdam via an in-house regular courier service using the train or their own bicycle. Part of the espionage material is currently available with the image bank of the Dutch NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Travelling by train became impossible after September 1944 due to the railway strike, so that the bicycle remained the only remaining means of transport. The messages were processed and translated in Rotterdam. A Philips Electronics’ employee, who had permission to travel to Switzerland for his work, arranged for the transport to Switzerland. From there the material ended up in England at MI6 and the Dutch Intelligence Service.

The southern provinces of Limburg and North-Brabant formed the Southern Netherlands region for the Albrecht group. This region, which also included the Biesbosch, was led by Willem van der Mast (Frans) from Rotterdam. He operated from the village of Hank in the Land of Heusden and Altena polder where he worked together with the ‘Group André’ of Jos van Wijlen (André). This group was not only involved in intelligence work but was active on a much broader front. Thanks to the efforts of Willem van der Mast, the village of Hank became the collection point for all work in the South.

This collaboration between Albrecht and André yielded unexpected opportunities. The Provincial Electricity Company of North-Brabant (PNEM) had its own internal telephone network called ‘Het Bijzonderapparaat’ (The Special Apparatus), of which existence the Germans were unaware of. Later, this network could also be linked to that of the provincial electricity company PLEM in neighbouring Limburg province. Because of his work, Jos van Wijlen had access to the transformer stations of the PNEM from which phone calls could be made. In this way, information from the entire South could be passed on by telephone to a central post in the town of Raamsdonksveer in the province of North-Brabant from where the messages were cycled to the village of Hank in no time. In the beginning, this was only used sparingly because of the risk of discovery, but that would change later. After the war, Van der Mast and Van Wijlen differed in opinion about who originated the idea.

In May 1944, Albrecht had a new opportunity to get the intelligence directly to London. On the initiative of Jan Marginus Somer, the head of the Bureau Inlichtingen (the Dutch Intelligence Service), the secret agent/radio operator Tony Visser, who had been dropped at Gorinchem, was assigned to the group. However, his radio was fatally damaged during the jump. The request to drop another radio was honoured and during the night of 5/6 June, a second agent landed with another device. The first radio could be illegally repaired with the help of Jos van Wijlen at Philips Electronics in Eindhoven, and now they had two transmitters. In addition to the possibility of physically delivering all messages via the Swiss route, they could now also make direct radio contact with London and therefore respond more quickly to requests for intelligence. These transmitters were relatively safe in the Land van Heusden en Altena polder and the nearby Biesbosch. German attempts by radio direction finding to determine the source were sufficiently hampered by the inaccessible nature of these areas and also because of an extensive warning system set up by group members. The result was that all nation-wide collected intelligence was assembled in Rotterdam and whatever was found eligible for transmission by radio subsequently went to Hank.

Due to intensified German controls in the summer of 1944, it was necessary to alter the courier routes. From then on, they mostly ran through the Alblasserwaard polder region and for that reason the area of the Alblasserwaard and the Vijfheerenlanden polder were added to the region of South Netherlands of Willem van der Mast. This merger and the resulting personal contacts would later lead to the creation of the crossing routes over the rivers and through the Biesbosch.

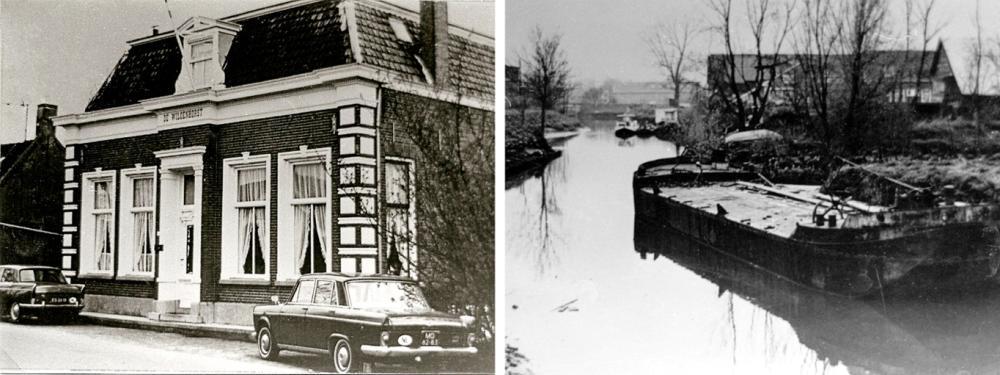

The centre of the Albrecht activities in the Alblasserwaard polder was the villa "De Wilgenhorst" in the town of Sliedrecht. This was the home of the parents-in-law of Bertus van Gool who lived there with his wife Jans. Van Gool had been involved in resistance work for some time and had ties with Albrecht. In the secret cellar of the house were weapons and other material and there was a constant coming and going of couriers who delivered their messages. Although Germans were quartered in the attic of the house, they never noticed any of these activities.

Once the Allied advance through France and Belgium gathered steam, it was decided in late summer of 1944 to move the transmitter to Rotterdam so as to prevent it from being located on the ‘wrong’ side of the frontline.

Post-war images of the ‘De Wilgenhorst’ mansion in Sliedrecht (left) and the starting point of the crossings (right). Source: Photo archive Historical Society Sliedrecht

An example of Albrecht’s espionage work can also be seen in the movie ‘A Bridge Too Far’. The message in which the Dutch resistance reported the presence of an SS Panzer Division near Arnhem was transmitted by Albrecht radio operator Tony Visser from a house in Rotterdam. This information prompted the English to carry out additional aerial reconnaissance which indeed confirmed the presence of the SS troops, but there was no question of Market Garden being called off.

On 17 September 1944, three British and American airborne divisions landed in the Netherlands. Simultaneously, a ground offensive was launched from the Belgian-Dutch border with the aim of reaching Arnhem via a narrow corridor. The Rhine Bridge at Arnhem indeed proved to be a bridge too far and after nine days the paratroopers had to retreat across the Rhine.

At the same time, this offensive heralded the beginning of the liberation of the southern part of the Netherlands. Both the headquarters of the 1st Canadian Army and the Dutch Intelligence Service, for whom the espionage material was mainly intended, had meanwhile been set up in the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven on September 19, 1944, but this did not automatically mean things immediately became easier for Albrecht.

Unlike the rest of the province of North-Brabant, the Land of Heusden and Altena and the village of Hank were not liberated and became frontline areas. As a result, the German military presence and controls expanded enormously. From then on, the messages from Hank were mainly brought across the frontline to Eindhoven by the members of the André Group, with all the risks involved. In the final winter of the war, many villages were evacuated and heavily shelled. At the end of the war, the Land of Heusden and Altena was therefore one of the parts of the Netherlands most affected by war violence.

Ferry connections were cut off and the German controls on bridges and roads became increasingly strict. In addition, the Allied air forces bombed and strafed any traffic they caught sight of. The ‘Special Apparatus’ now proved its worth, but transferring physical material such as maps, photos and reports became increasingly difficult. The transport of espionage material that was put in the mail bags by a loyal postal employee and intended for the Land van Heusden en Altena also became impossible after he was arrested.

An alternative route was devised for this mail traffic. From the town of Sliedrecht, the Albrecht members Jan Visser and Koos Meijer brought the mail by rowing boat straight through the Biesbosch to Hank. During that period - mid-October 1944 - there were hardly any Germans in the Biesbosch and this route was therefore still relatively safe.

At the end of October 1944, the villages of Drimmelen and Lage Zwaluwe, situated on the southern edge of the Biesbosch, were liberated and Raamsdonksveer, from where the messages were transmitted via the ‘Special Apparatus’, was now also in liberated territory. The result was that the physical intelligence material from the occupied North could in principle be brought directly to the liberated South.

For the Albrecht Group, this meant that more or less safe routes had to be devised to achieve this. These routes ran straight through the Biesbosch, which by now formed the front line, ran between Sliedrecht and Lage Zwaluwe and between Werkendam and Drimmelen. This was the beginning of the crossings or line-crossings that took place until the very last day of the war.

Definitielijst

- Bureau Inlichtingen

- Set up in November 1942 in London by the Dutch government in exile after the completely botched agent droppings in occupied Netherlands (the ‘Englandspiel’). This new service cooperated with MI6 and was very successful

- collaboration

- Cooperation of the people with the occupying forces, more generally spoken the term for individuals who cooperate with the occupying force is collaborator.

- Holocaust

- Term for the destruction of European Jewry by the Nazis. Holokauston is the Greek term for a completely burnt sacrifice.

- mid

- Military intelligence service.

- railway strike

- This was announced on the radio and complied with by the Dutch railway staff on 17 September 1944. The railway strike was intended to support the allied plan Operation Market Garden. After the allied airborne landings had failed, Dutch railway staff remained on strike until the liberation.

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

The Crossings

The name Line-crosser was in principle used to refer to anyone who made the journey across the front lines to liberated territory or vice versa. In practice, this usually meant crossing one or more rivers. In addition to the crossings through the Biesbosch, rivers were also crossed at other places to reach liberated territory. In Limburg province, across the Maas River and in various places across the Waal River. However, because the banks of these rivers were guarded on both sides resulting in frequent fire exchanges, these journeys were very risky and were probably not very numerous and will not be discussed further in this article. Also, crossing with the sole purpose of escaping to liberated territory was strongly discouraged. The Allied authorities in the South of the Netherlands were very wary of spies and saboteurs and anyone who had made the crossing was only released after a strict screening. The capacity for these interrogations was very limited, so the Allies just did not want them, and this was also made known in the underground press.

This did not apply to Albrecht's members, because there was a constant need for information about the military and economic situation in occupied Netherlands. In the meantime, they were also prepared for the new situation. Willem van der Mast, Albrecht's sector leader in the South of the Netherlands and the Albrecht members from Sliedrecht and Werkendam had already made their plans in advance in case it ever got that far.

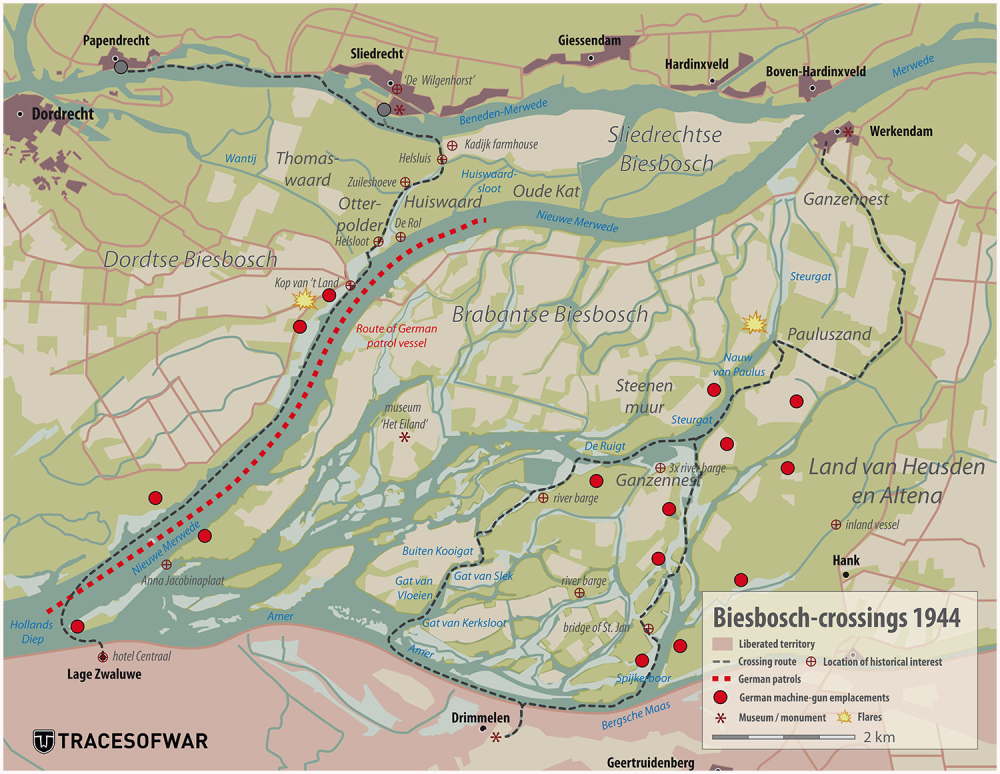

After a few reconnaissance crossings, two crossing routes emerged more or less simultaneously, both of which took into account how the German military presence in the area could be circumvented as much as possible.

The Sliedrecht-Lage Zwaluwe route

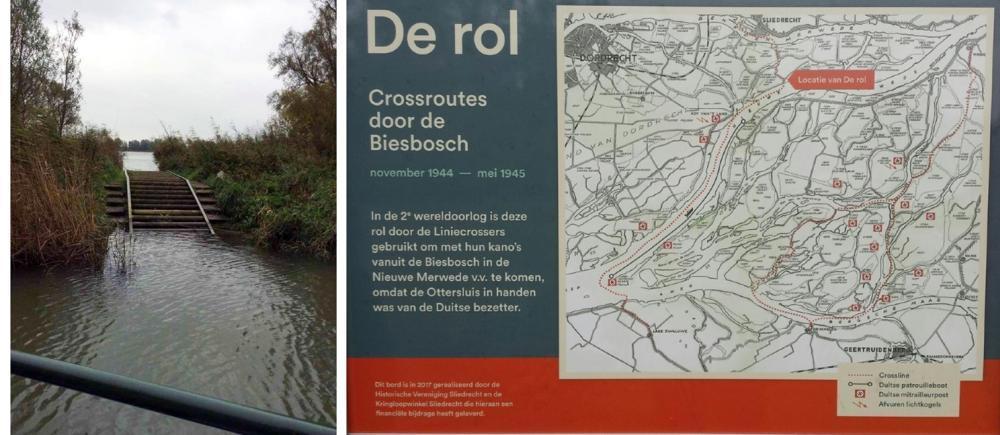

This route mainly ran along the large rivers. Initially, the intention was to sail through the Biesbosch to Drimmelen. This was first tried out on November 6, 1944, by Albrecht members Bertus van Gool and Co Bakker but it turned out not to be a success. The outward journey went without problems, but in subsequent days the German presence in the Biesbosch had increased to such an extent it was no longer safe to return via the same route. A more westerly route to Lage Zaluwe was considered as an alternative. This route, which was explored about a week later by Koos Meijer and Jan Visser, turned out to be successful and remained in use until the end of the war. Disadvantages of this route were, apart from the Germans, the often high waves at the turn towards the Amer River and the obstacles created by sunken river barges in the Nieuwe Merwede River.

In the dead of night, the crossers would usually depart from De Wilgenhorst villa and sometimes from other places in Sliedrecht. From there they would cross small creeks and use a portage to reach the wide Nieuwe-Merwede River and then continue south, thereby circumventing the dense maze of creeks and waterways of the large Biesbosch, and then continue east along the Amer river to finally arrive at the small harbour of Lage Zwaluw in the liberated south.

“De Rol” portage in present times (left). Information board that displays in detail the various routes of the crossers. (right) Source: Photo archive Historical Society Sliedrecht

The most dangerous part of the route was the Nieuwe-Merwede river which is in between 325 and 695 metres wide. German patrol boats were constantly cruising on the river and at a number of places along the bank were machine gun posts located. Flares were regularly fired that brightly illuminated the river and forced the crossers to seek shelter in creeks or in the reeds along the banks.

The length of this route was approximately 15 kilometres and took some 4.5 hours to complete when conditions were favourable. Depending on the type of boat used, or in the event of an unfavourable tide or other setbacks, this could take much longer or one had to return.

The Werkendam-Drimmelen route

This route was initially explored by Arie van Drie and Piet van den Hoek, whereby the first leg was by foot through the Werkendam polder to a spot where small boats had been hidden deep inside the polder, at the Bruine Kill creek. From there, they would follow the waterways that fringed the eastern borders of the Biesbosch and ran straight to the Amer River, south of the Brabantse Biesbosch. From there they would cross the river to the port of Drimmelen in the liberated South.

When warranted by prevailing circumstances, an alternative route could be chosen from where the boats were hidden. This route followed a trajectory of creeks and waterways that ran straight through the core area of the Biesbosch and also ended up at the Amer River from where the port of Drimmelen could be reached.

There was also a considerable German presence on this route, such as in the Steenen Muur polder and in the Pauluszand polder, where they had set up machine gun positions and from where they could fire flares.

This route was approximately 13 kilometres long, physically demanding and took approximately 4.5 hours when conditions were favourable.

How did a crossing proceed?

Except when the moonlight was too bright or drift ice was floating on the rivers, line-crossings happened almost every night and often with multiple boats whereby optimal use was made of favourable tide conditions as much as possible. With a tidal range of 2 metres, there was a very strong current in the rivers. The largest part of both routes ran (south) westwards, which meant that the boats benefitted most when the tide rose. This saved rowing and therefore minimised noise. Bad weather was also an advantage, because it hampered German surveillance activities, and it was then hard to be noticed anyway.

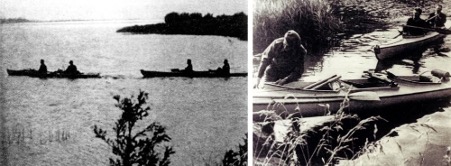

Images from a 1949 documentary film in which a crossing was re-enacted by the actual crossers. Above images show rowing canoes on open water and the land crossing at 'De Rol' (portage). Source: Oorlogsbronnen

To defend themselves, the crossers usually carried pistols and stenguns. All material was packed waterproof and weighted so that, in case of detection by the Germans, it could be thrown overboard and sink immediately. This applied to everything of which its origin could be traced back to liberated territory. The oars were wrapped in cloth to reduce noise and absolute silence amongst the rowers was required.

During their crossings, they usually wore British uniforms and were provided with forged English ID papers, hoping they would be considered prisoners of war in case of an arrest. In practice, this did not work. Two (non-Albrecht) crossers, who tried to ferry English soldiers across the Rhine, were dressed in British uniforms but immediately shot dead once it was found they could not speak any English.

Initially, the crossings were only intended to ferry intelligence from the occupied zone, but soon passengers had to be taken along as well. These passengers were a mixed bag of stranded allied soldiers but also people who were wanted by the Germans. As liberation drew closer, the Dutch government increasingly tried to get a clear picture of the situation in the still occupied part of the country. This was to prepare as much as possible for the most urgent needs and also to draw this to the attention of the Allies. For example, all kinds of experts were ferried to the liberated south - sometimes even with the knowledge of the Germans – to report on the dire food situation, the state of the ports and the lack of medicines, amongst others.

Various types of boats were used for the crossings. The fastest and most manoeuvrable were a canoe or a dugout, but these could not take passengers. Moreover, in bad weather conditions they quickly scooped water and required continuous bailing. Rowing boats could take passengers but had the disadvantage they were slower. Later, they availed of a few Canadian and American canoes that were not only larger but also equipped with an electric engine and watertight compartments.

The Germans were of course aware that crossings took place and were therefore alert and vigilant. To remain out of sight of the German positions as much as possible, they rowed alternately along one or the other side of the river. In places where there were Germans on both sides, they used the middle of the wide river. Despite all these efforts, it happened repeatedly that the crossers were spotted and shot at. People were injured, but miraculously they usually managed to get away in the reeds or in creeks where they were almost invisible, after which it was a matter of waiting until it was safe again to resume their journey. Overall, a crossing could take a very long time if mishaps occurred. It was also a harsh winter with sometimes very low temperatures, fog, snow and ice.

Dire situations also occurred where people had to save themselves by swimming or crossing minefields on foot. In any journey of this kind, it stands to reason that the crossers and their passengers suffered the necessary hardships. It also happened regularly that continuing any further was impossible and the only option left was to return to the place of departure.

Piet van den Hoek and Adriaan Keizer in their canoe (probably post-war photo). Source: Stichting Liniecrossers Sliedrecht

Until the time the Biesbosch was almost completely evacuated in January 1945, they could also rest or spend the night at farmers' houses. A number of these farmers had already provided shelter to people in hiding or provided them with food and work. For them, helping the good cause was a natural thing to do. Well-known places included the Kadijk farmhouse near the locks of the Helsluis (demolished) and the Zuileshoeve farmhouse (still exists) along the Huiswaardsloot. They could also count on the help of the lock keeper of the Helsluis (Willem van Alphen), who ensured they could pass quickly.

Often the routes were also rowed in sections, with another crosser taking over the passengers or cargo halfway through. For example, passengers were first transferred to the Beneden-Merwede river, after which the journey was continued and completed in the village of Werkendam by one or more other crossers. The Albrecht crossers were also not necessarily tied to their place of residence as far as departure and arrival were concerned. The crossers from Werkendam also went to Sliedrecht and vice versa for the crossers from Sliedrecht.

From January 1945, the crossings were organised in such a way that they increasingly operated from liberated areas. In the village of Lage Zwaluwe, the crossers had their base in Hotel Centraal where they could sleep, eat and relax. From here, they would visit occupied areas where they would meet with their families again. The British Brigadier John Hackett, who had escaped from German captivity after Market Garden and was brought to Lage Zwaluwe by two crossers from Sliedrecht, described the reception at the Hotel Centraal in his book ‘I Was a Stranger’, as follows:

“The room was full of tobacco smoke; there was a stove. Men in khaki combat gear were sitting or standing around the stove. It was too good to be true. On tables, against walls and on windowsills were maps, steel helmets, balaclavas, army overcoats and enamel plates. Here and there were rifles and the floor was littered with knapsacks, bread bags, belts and bedding. Amid this familiar and pleasant-looking mixture of equipment from the British army in the field, I dropped into a chair. It felt like I was amongst my own people again”[1]

How were the crossing operations organised?

For the crossers who operated under the flag of the Albrecht group, this was different than for the Wild Crossers. The Albrecht crossers operated under the direction and on behalf of the Dutch Intelligence Bureau in the liberated town of Eindhoven, which in turn also closely collaborated with the Allied intelligence services.

The requests for specific information about the situation in the occupied North, and the orders to bring people whose arrival in the liberated South was desired or vice versa, largely came from the Dutch Intelligence Service. This information could pertain to military matters, but also the economic situation, the food situation and the destruction in the occupied part of the country. It was not exclusively intelligence gathered by Albrecht that was ferried across; other groups also called on the crossers to transport their material.

The Wild Crossers, on the other hand, worked autonomously and considered the cross-country work mainly as an extension of their other resistance activities. Their journeys mainly concerned bringing people who were wanted by the Germans to safety, including many Allied pilots who wanted to return to their own lines. Their work was also of great significance and should certainly not go unmentioned. They used more or less the same routes, and the experienced Wild Crossers also collaborated with Albrecht's men when necessary.

The trips were coordinated by the so-called Crossmasters. In the town of Sliedrecht, this was Bertus van Gool from the Wilgenhorst villa. The couriers delivered their information consisting of reports, maps or photos at the Wilgenhorst, after which these were processed for further dispatch. In Werkendam, Cornelis Visser acted as Crossmaster from his home on the Vissersdijk and in liberated North-Brabant province, Jos van Wijlen (‘Captain André’) who had previously led the resistance group André, now commanded the crossers of Albrecht.

Because the situation in the occupied North became increasingly dire, and for men in certain age groups also increasingly dangerous, more and more people tried to reach the safe South by chance. However, these often-inexperienced crossers did not contribute to safety and because of the ‘crowds’ on the water the chance of discovery and shootings became increasingly greater.

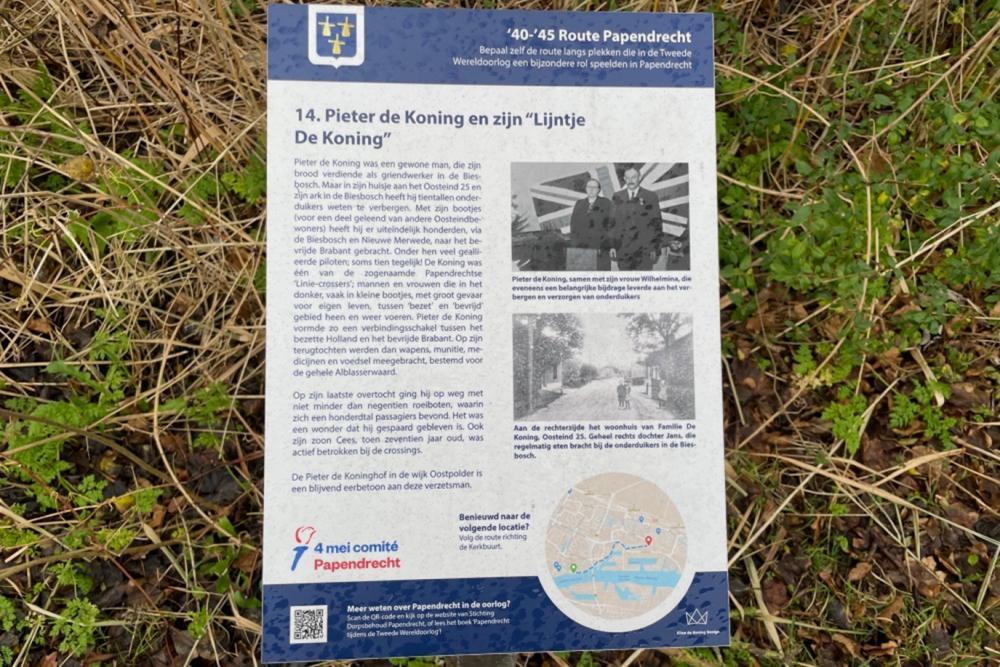

Probably the best known of the Wild Crossers was Pieter de Koning from the town of Papendrecht. He already became involved in the resistance in the early stage of the German occupation and because of his work in the willow forests knew the Biesbosch like the back of his hand. Along a route he had set up and named “Lijntje van De Koning” (De Koning's little ferry-line), he and his sons Kees and Flip ferried a large number of people to safety during an unknown number of trips. He himself spoke little about it, but there were probably more than a hundred.

Definitielijst

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

Who were these crossers?

The early crossers already had ties with Albrecht. As the work increased, others were recruited who had in common that they were familiar with the rivers and the Biesbosch. They had usually already been active in the resistance, and some had previously belonged to the Biesbosch Group. Ultimately, 21 men were directly active as crossers for Albrecht. Most of them came from the places around the Biesbosch, but for example Frans Hoffmans and Koos Hoevenaar, the father of no less than 13 children, came from Waalwijk and Lage Zwaluwe respectively. At the time they were asked to do the cross work, they were already living in liberated territory! Among the ranks were also a number of inland waterway skippers whose ships had been confiscated by the Germans and who therefore had a score to settle with the Germans.

Crossers operating for the Albrecht Group and the Dutch Intelligence Service 'Bureau Inlichtingen'

| Name | Alias | Place | Nr. of Crossings |

| Arie van Driel | Aike | Werkendam | 53 |

| Piet van der Hoek | Schele (Squinting) Piet | Werkendam | 37 |

| Jan Visser | Grijze (Gray) Jan | Sliedrecht | 37 |

| Jan de Landgraaf | Dove (Deaf) Jan | Sliedrecht | 30 |

| Jacobus Bakker | Alblas | Sliedrecht | 25 |

| Albert Kunst | Sliedrecht | 25 | |

| Jacobus Meijer | Koos | Sliedrecht | 25 |

| Cornelis Bolijn | Zwarte (Black) Kees | Sliedrecht | 23 |

| Kees van der Sande | Burgers | Sleeuwijk | 22 |

| Frans Hoffmans | Frans | Waalwijk | 18 |

| Willem van Veen | Wim I | Werkendam | 18 |

| Adriaan de Keizer | Adriaan III | Werkendam | 16 |

| Pieter van Dam | Hardinxveld | 15 | |

| Cornelis Visser | Kees V | Werkendam | 12 |

| Leendert van Kempen | Leen | Werkendam | 10 |

| Jacobus Hoevenaar | Lage Zwaluwe | 8 | |

| Bertus van Gool | Bertus | Sliedrecht | 6 |

| Leendert van Beugen | Sleeuwijk | 4 | |

| Johannes Rombout | Jan Staart (Tail) | Dordrecht | Unknown |

| Arie de Boon | Hardinxveld | Unknown | |

| Cornelis de Boon | Hardinxveld | Unknown |

Non-aligned 'wild crossers' (incomplete)

| Willem Leenman | Hardinxveld | Unknown |

| Willem Baars & Willem Boot | Hoekse Waard | Unknown |

| Pieter de Koning en Zn | Papendrecht | Unknown |

| Joop Hollebrands | Sliedrecht | Unknown |

| Ab van Ballegooyen | Sliedrecht | Unknown |

| Bernard & Jo Lanser | Sliedrecht | Unknown |

| George Bicker & Dirk de Rouwe | Sliedrecht | Unknown |

| Cornelis 'Kees' van Woerkom | Sliedrecht | Unknown |

Definitielijst

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

The stories of some crossings

While hundreds of crossings took place, hardly any of them has been documented. However, for various reasons, testimonies have been given about a few of them. Without wanting to do injustice to any other testimony, a random selection of some of these is presented below.

- Crossing of General Hackett and associates

- Insulin for occupied Netherlands

- The report of a crossing by Piet van den Hoek

- The last crossing by Aike van Driel

- Some crossings that went wrong

February 4, 1945, the crossing of General Hackett and associates

After the failure of the Battle of Arnhem, several hundred British soldiers had been left behind in the Netherlands, whether or not wounded or having escaped from captivity. Many had gone into hiding in the Veluwe forests. More than a hundred of them escaped across the Rhine river during ‘Operation Pegasus I’. A similar second operation ‘Pegasus II’ failed, after which the only viable way to reach their own lines again was via the Biesbosch.

Among those who remained behind were also a number of high-ranking officers and physicians. Strangely enough, the British MI9 – which was aware of the existence of the crosslines – and the Veluwe resistance did not come up with the idea earlier, but in February 1945 the time had come. Brigadier John Hackett, divisional physician Colonel Graeme Warrack, surgeon Alexander Lippman-Kessel and a few other officers set off separately to Sliedrecht to escape from occupied Holland through the Biesbosch.

Hackett had sustained a serious abdominal wound during the fighting and was operated on and nursed by Lippman-Kessel in the Sint Elisabeths Gasthuis hospital in Arnhem. He was smuggled out of the hospital by members of the Arnhem resistance. He stayed for four months with the De Nooij sisters on the Torenstraat in Ede, whom he became very fond of and with whom he also kept in touch after the war. With the forged identity of ‘Mr van Dalen’ and having been provided with a pin on his coat that identified him as a person with a hearing impediment, he left Ede on a bicycle. Via the town of Maarn, where he was joined by his fellow officers, they continued further south-west to Sliedrecht where he said goodbye to his companions.

In his memoirs, Hackett describes the atmosphere in the village. He saw exhausted people, mainly women and elderly people, but he did not notice any young men at all. This image fitted a village that had already undergone a number of raids, where men were arrested and transported to Germany for forced labour.

The first part of his journey to his own lines was by rowing boat that departed from a factory site on the Merwede river. After a short hour of rowing upstream, he arrived at the Kadijk farmhouse inland on the other side of the river. There he was met by the crosser Co Bakker who guided him through reed fields and over ditches to the next departure point.

The next crosser in line was Koos Meijer. The Canadian canoe was loaded, Hackett got in and they went through the Huiswaardsloot towards the ‘De Rol’ portage where the boat had to be pulled overland for a while. There he found out they were not the only ones on the water that night. Several people were on the narrow piece of land awaiting further transport.

They arrived at the Nieuwe-Merwede river and headed towards Lage Zwaluwe. This wide river was the most dangerous part of the journey with German posts on both sides. There was a strong wind and the canoe was rocking quite a bit. The journey went without too many incidents and the Kop van ’t Land was passed without any problems. After rounding the Jacomien floodplain they headed for the Amer river. It was the early morning February 5, 1945, when Hackett, numbed by the cold, was dropped off by Koos Meijer at the harbour of Lage Zwaluwe.

In 1967, the Dutch TV channel NCRV aired a documentary about the crossers. In this documentary, Hackett met his former helpers who recalled it had been a quiet trip. In Hackett’s memory, however, there had been a lot of shooting from both sides of the water, although none was targeted at them. This does show the difference in perception and what the crossers had become accustomed to.

Graeme Warrick had already arrived in Lage Zwaluwe an hour earlier and a few days later, a few more officers arrived, including Alexander Lipmann Kessel. Books about their experiences during and after the Battle of Arnhem were published by all three after the war. Without exception, they were extremely complimentary about the people who had risked their lives for them.

The following day, the BBC broadcast the message: ‘The goose has flown’, which meant that all the helpers knew of Hackett’s safe arrival.

After Hackett’s death, his family donated some objects that commemorate his escape to the Biesbosch Museum ‘Het Eiland’, where they are now part of the exhibition about the crossers.

Insulin for occupied Netherlands

In the winter of 1945, the situation in occupied Netherlands became dire. There was not only a shortage of food, but literally of everything. Because soap and other cleaning agents were no longer available, hygiene collapsed with all due consequences. An even bigger problem was that medicines were also running out, especially insulin, which immediately endangered the lives of thousands of diabetics. This insulin largely originated from Organon Pharmaceuticals in Oss in the liberated South and from where supply to the occupied North had come to a standstill. Stocks had been built up as a precaution, but these too ran out.

Cries for help from doctors and from Albrecht leader Kees Brouwer – who personally advocated to the Dutch Intelligence Service the need to supply insulin – were ultimately successful. However, two air droppings had no effect as distribution was delayed and the insulin did not reach the people who needed it.

The crossers were also called in. In the night of 24 to 25 February 1945 they brought 6,500,000 units of insulin to Sliedrecht for the first time. In subsequent weeks another 9,500,000 units followed as well as other medicines and resources for which there was an urgent need, such as typhoid vaccines, vitamins and diphtheria serum. Professor of General Surgery in Utrecht and coincidentally also Prince Bernhard's personal physician, Jan Nieboer, played a role in this. He was listened to, of course, and his order list of medicines was delivered to Utrecht a short time later. After that, hardly any boat left for occupied territory without medicines on board.

In the Wilgenhorst villa, people soon didn't know where to store the insulin. The cellar was full and crossmaster Bertus van Gool had no other option than to store the insulin in his living room. In case of ampoules carrying English imprints, a local doctor would change these for a Dutch label. Couriers then transported the insulin via Utrecht to Amsterdam, where the underground doctors’ collective, the Medisch Contact, ensured further distribution to the locations where it was needed most.

Many people owe their lives to these medicines. After the war, Bertus van Gool stated that this had been their finest assignment. Transporting messages and people was important work, but they saw little direct result from it.

Report of a crossing from Werkendam to Drimmelen by Piet van den Hoek, December 1944

“It is with some trepidation that I attempt to document one of our crossings on paper, as it is nearly impossible to convey the deepest emotions that come over you on such a journey.

It is a very dark night when we, Aike [van Driel] and Piet [van den Hoek], report to Kees [Visser] and collect the items we must bring to liberated territory. The orders are given in hushed voices and every nerve in our body is tense.

Finally, we both set off. First, we have to clamber over a houseboat and then walk for about half an hour across the polder before we arrive at the Bruine Kil creek where we had left our camouflaged boat after our last trip. We are waiting for a while before we leave, because the tide is still dead and we want to wait for the low tide when the current is favourable to row to Drimmelen; but it is not that far yet. We stand there waiting tensely and finally it’s time to start our journey. I take the oars of the dugout and Aike sits in the back with his stengun cocked. We row out of the Bruine Kil creek and at the end we need to cross the water to the opposite bank, because to our left is the Pauluszand polder where the Germans have set up their guard posts. We hear them talking to each other, so it is important to pass this point as quietly as possible.

Then we approach the first dangerous spot. I was on edge and pulled the oars through the water very slowly; the current doing most of the work. While I have my stengun lying next to me, Aike sits with his stengun ready. At the slightest sign of us being detected, he will be forced to shoot. A sigh of relief escapes our throats when we have passed this dangerous spot. But this is only the start of the two-and-a-half-hour journey. We row through a straight-lined waterway called the Nauw van Paulus and then arrive at the wide Spijkerboor creek without incident. After rowing a bit further Aike suddenly speaks: ‘Wait a minute, I see a boat crossing to the other side’. The tension rises. Out of the blue, a few bursts of fire from Aike’s stengun, after which it becomes frighteningly quiet for a moment. But then suddenly the Germans fire flares and it seems like broad daylight. We retreat into the reeds, where we tensely await further events. In great suspense we stayed put for about an hour and a half before we dared to go further.

Finally, we went on, but we had our ears and eyes wide open, because disaster could strike us at every creek or river bend. Fortunately, nothing else happened that night and we could finally give our password to the guard in Drimmelen: ‘The hare has been shot’. Now we could also hand over our messages etc. to the courier who took them as quickly as possible to André (Jos van Wijlen) in Sprang-Capelle. We were grateful and happy that we had completed this trip successfully as well. But the Germans were less fortunate, because that night they brought three wounded soldiers to the hospital in Werkendam.”[2]

March 18, 1945, the last crossing of Arie ‘Aike’ van Driel

For a long time, trips either went without incidents or the crossers had narrowly escaped arrest and imprisonment. After it had failed the previous night, a new attempt was made to bring four agents of the Intelligence Bureau to occupied territory. The tide and the position of the moon were not ideal that night, but it was decided to set off anyway.

Five boats with a total of eight passengers left the harbour of Lage Zwaluwe on Sunday evening, March 18, 1945, in the direction of Sliedrecht. Agent Jan Pieter van Alten, who had been assigned to carry out espionage work in Germany, was in a canoe with Frans Hoevenaar. Aike van Driel transported three people. Alida Storm van Leeuwen, Wim Westra Hoeksema and Lex Lindo were on their way to the east of the country with various assignments.

Close to the hamlet of Kop van ’t Land, they were met by a number of boats with ‘wild crossers’ who had been spotted by the Germans earlier on. These were arrested by the crew of a German Sturmboot (a small assault boat) that returned a short while later. When Aike van Driel – who had waited in the lee of the reeds – decided to return to Lage Zwaluwe after it had calmed down again, another Sturmboot appeared at the confluence of the Nieuwe Merwede and the Amer rivers. Escape was no longer possible when the guns of the boat’s crew were aimed at them. Meanwhile, they had managed to throw all compromising items overboard, including a bundle of 100 guilder notes that came loose and floated on the water. The boat was towed to the Kop van ’t Land and Aike and the three agents were brought ashore.

The other boats were not discovered and managed to reach De Wilgenhorst unscathed. The arrest of Aike van Driel caused quite a stir. With 53 crossings, he was the most experienced of the group and also knew all the ins and outs of the organisation. Still, the other crossers were convinced that given his character, Aike would remain silent and that turned out to be true.

In the meantime, Kees van de Sande was arrested at his home and in the presence of his wife. He too was an experienced crosser and the district commander of the resistance in the Land van Altena. Their paths would soon cross.

After being brought ashore, the arrested men were transported via Oud-Beijerland to the prison on the Noordsingel in Rotterdam. From there, Aike van Driel was transferred to the prison on the Wolvenplein in Utrecht. It turned out that Kees van de Sande was there as well. It is not certain whether the two men were in contact during their time in the prison, but it is known that they were severely beaten during the interrogations. The resistance made several attempts to have both men released or at least to prevent them from being shot. Ransom was even said to have been paid, but a drunken German officer decided otherwise. Against all promises, Aike van Driel (39) and Kees van de Sande (27) were shot in Fort De Bilt in Utrecht on April 30, 1945, the day Hitler committed suicide. Immediately after the liberation, their bodies were transferred from Utrecht to Werkendam where they were buried next to each other.

Some crossings that went wrong

The crossers were regularly shot at during their journeys, but lives were lost on both sides and an unknown number of people were injured. In retrospect, it is a miracle that there were not more victims. To quote one of the crossers: ‘it was tricky stuff’.

On February 11,1945, Gerrit Visser and Gerard Schrikker, who were wanted by the Germans, were supposed to make the crossing with the help of a wild crosser from Sliedrecht. Due to the unfavourable weather, the wild crosser wanted to postpone the crossing. However, the two men decided to go anyway. Their canoe capsized and they drowned. Twenty years later, former resistance members said that shortly after the incident, they had found two bodies on a beach at the Thomaswaard. They were also supposedly buried there, but recent searches have been in vain.

Accidents also took their toll. The courier and resistance fighter Riet van Grunsven crossed to and from occupied Netherlands four times. The fourth time it went wrong, she slipped and suffered permanent injuries. She spent the rest of her life in a wheelchair.

During the very last crossing on the night of May 4 to 5, 1945, the arrival of a German patrol boat forced the crossers to leave their own boat behind. The men had no choice but to continue walking, wading through the mud and swimming. A minefield also had to be crossed. Passenger Sjefke stepped on a mine that exploded and he later died from his injuries. Crosser Adriaan de Keizer was barely saved from drowning. Eventually they found a leaky boat with which they were able to save themselves.

On January 13, 1945, Piet van den Hoek and Thijs Peele - who acted as a replacement for Aike van Driel who suffered from a hand injury and was therefore unable to row - made a crossing from Drimmelen to Werkendam. The journey went well until they were discovered and shot at. They had to leave their boat behind at the Jannezand polder from where they continued on foot. In an attempt to steal a rowing boat from the Germans they were arrested. Fortunately, the Germans were not too ill-disposed towards them and after some detours they ended up in a work camp in Amersfoort from where they were able to escape after a few weeks. Eventually they returned to Werkendam on foot and the cross-country work was simply resumed.

Definitielijst

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

After the War

On May 5, 1945, the war came ended. It must have been a huge transition for these men from the exciting and nerve-racking existence of crossers back to their normal everyday lives. In preserved interviews the crossers were generally modest about their role at that time. Words like comradeship and the urge for freedom were used, but they also testified about how exciting and scary the work was. Images of the reunions look animated, but it is also known that PTSD played tricks on several of the men later in life.

It's impossible not to have a great respect for the crossers' achievements when looking at what they've accomplished. They risked their lives under often harsh conditions and always returned from the safe South to the occupied part with all the associated risks. The result of the intelligence work they transported is difficult to measure. This also applies to the passengers they transported, but the medicine transports undeniably saved many lives.

The Albrecht crossers were awarded many decorations after the war. Aike van Driel (posthumously), Kees van de Sande (posthumously), Piet van den Hoek and Jan de Landgraaf received the Military Order of William 4th Class. Eleven crossers were awarded the Bronze Lion, and six others received the Bronze Cross. In addition to Dutch decorations, in a number of cases the American Medal of Freedom, the British King's Medal for Service in the Cause of Freedom and other foreign awards were also awarded.

It should not go unmentioned that the crossers did not do their work alone. They received help from other men and women who were also active in the resistance, from the farmers in the Biesbosch, from local doctors and villagers who turned a blind eye. Last but not least, their own wives, some of whom also played an active role.

Military Order of William, 4th Class | |

| Arie van Driel (posthumously) | Werkendam |

| Kornelis Pieter van de Sande (posthumously) | Sleeuwijk |

| Cornelis Pieter van den Hoek | Werkendam |

| Jan de Landgraaf | Sliedrecht |

| Bronze Lion | |

| Jacobus Bakker | Sliedrecht |

| Cornelis Leendert Bolijn | Sliedrecht |

| Pieter van Dam | Hardinxveld |

| Desidirius Hubertus van Gool | Sliedrecht |

| Jacobus Cornelis Hoevenaar | Lage Zwaluwe |

| Franciscus Johannes Maria Hoffmann | Waalwijk |

| Albert Kunst | Sliedrecht |

| Jacobus Meijer | Sliedrecht |

| Johannes Rombout | Dordrecht |

| Cornelis Visser | Werkendam |

| Jan Visser Jr. | Sliedrecht |

| Bronze Cross | |

| Leendert Gerardus van Beuge | Sleeuwwijk |

| Arie de Boon | Hardinxveld |

| Cornelis de boon | Hardinxveld |

| Adrianus de Keizer | Werkendam |

| Leendert van Kempen | Werkendam |

| Willem van Veen | Werkendam |

The ‘wild’ crossers fared less well when it came to decorations. They mainly received foreign awards for their help to allied soldiers. Pieter de Koning was awarded the British King’s Medal and the American Medal of Freedom for this. The same honour was also bestowed upon Willem Leenman from Hardinxveld, Cornelis ‘Kees’ van Woerkom from Sliedrecht and the lock keeper of the Helsluis Willem van Alphen.

In 2016, an article named ‘The lost cash book of the crossers’ was published in the BN De Stem, a regional newspaper. The article pertained to a recovered cash book of the BS (‘Binnenlandse Strijdkrachten’/Domestic Armed Forces) which revealed that a number of crossers had been paid for their work at the time. While this was already known from sources in the National Archives, there is still a sense of surprise in the article itself. All things considered, that is a strange reaction. The Albrecht crossers were formally appointed by the Dutch Intelligence Service (Bureau Inlichtingen) and operated from liberated areas on their behalf. They wore army uniforms and had official papers. Because they were away from home for a long time, they could not earn any income and they – and their families, if applicable – were dependent on these payments for their livelihood. Furthermore, during the occupation, many payments were made from the National Support Fund to people in hiding and the resistance.

Definitielijst

- Bureau Inlichtingen

- Set up in November 1942 in London by the Dutch government in exile after the completely botched agent droppings in occupied Netherlands (the ‘Englandspiel’). This new service cooperated with MI6 and was very successful

- resistance

- Resistance against the enemy. Often also with armed resources.

The Linecrossers today

In the towns of Drimmelen, Lage Zwaluwe, Sliedrecht and Werkendam, one can find monuments, street names and plaques that commemorate the work of Albrecht and the Line-crossers. They are unanimously striking bronze monuments of tough men dressed in winter clothing and wellington boots.

In 2017, memorials were placed in Drimmelen and at the Biesbosch Museum in Werkendam to commemorate the contribution by the farmers from the Biesbosch during the Second World War.

Two foundations keep the memory of the crossers alive. The Stichting Liniecrossers Sliedrecht (Line-crossers Foundation of the town of Sliedrecht) has set up an exhibition in the basement of the Wilgenhorst villa that can be visited by appointment. In addition to photos and documents, there are also several dioramas on display that depict the circumstances of the cross work.

The Biesbosch Museum ‘Het Eiland’ (The Island) also permanently focuses on the history of the Line-crossers. There is an original boat as well as awards, weapons and several objects that the museum received from Hackett’s relatives.

The Stichting Biesbosch in Beeld (Foundation Biesbosch in Pictures) made a feature film of over 40 minutes, called ‘Biesbosch onder Vuur’ (Biesbosch under Attack), in 2015 with the cooperation of local extras. The film tells the story of young Frank who tries to obtain insulin for his sister who suffers from diabetes. It is a fictional but fitting story that takes place in a historical setting and is based on correct facts.

Finally, on YouTube one can find various interviews with the crossers themselves, or with their children who reminisce about their fathers.

Notes

- John Hackett, Ik ben een Vreemdeling geweest, 1e druk, p. 191.

- Piet van den Hoek, Biesbosch Crossings, pp. 61-62.

Information

- Article by:

- Jan de Jager

- Translated by:

- Simon van der Meulen

- Published on:

- 19-10-2025

- Feedback?

- Send it!

Related sights

Related books

Sources

- BAARDMAN, C., Modder is gevaarlijk, Zaklantaarn Pocket, 1966.

- DRIEL, BERT VAN, Biesbosch commando, Brabantia Nostra, 1987.

- FIJNEKAM, LEEN & VAN BOKHORST, ALFONS, De Biesbosch in de Tweede Wereldoorlog, Eigen uitgave, 2021.

- HACKETT, JOHN, Ik ben een vreemdeling geweest, Bosch & Keunig, 1979.

- HOEK, PIET VAN DEN, Biesbosch Crossings 1944-1945, Kok Voorhoeve, Kampen, 1993.

- LANGEBEEKE, PETER-WILLEM, Operatie Bograt, m.m.v. Oorlogsmuseum Veen, 2023.

- SIMONS, J., Liniecrossers, Omniboek, 2021.

- WIJNGAARDEN, P. VAN, Papendrecht tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, WW2Books, Papendrecht, 2020.

- NCRV TV documentary ‘Grensrechters van de Biesbosch’, 1967.

- Video STS Producties, Line Crossing 1991, including some interviews with former crossers. Can be viewed on Youtube .

- Stichting Liniecrossers Sliedrecht.

- Stichting Verzetsgroep De Liniecrosser, Wagenberg .

- Stichting Omzien & Gedenken.

- Schapendonk, Nico, ‘Het verloren kasboek van de liniecrossers’, on: BNDeStem.nl, 09-10-16.

- HantjeDeJong.nl.

- Website of H.W.G. van Blokland-Visser.